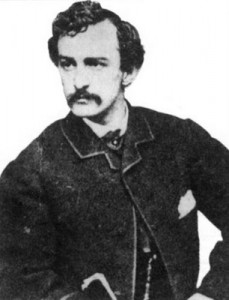

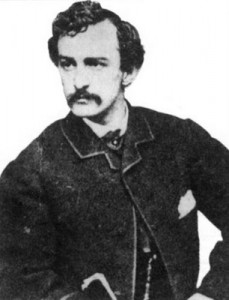

John Wilkes Booth

by Jeffrey S. Williams

The son of a well-known actor, John Wilkes Booth was an accomplished actor by 1859 and was performing in Richmond, Virginia, in November of that year when he spontaneously joined the Richmond Grays, a local militia unit, when rumors abounded that John Brown, of Bloody Kansas and Harper’s Ferry fame, was going to be rescued by abolitionists. The unit was already on a train when Booth arrived. He talked his way aboard by purchasing a jacket and trousers from some of the troops already aboard. When the Grays arrived at Charlestown, instead of quelling an uprising that didn’t occur and they provided courthouse security instead. Booth and the Richmond Grays were present when Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859. He stood in front of the gallows a few yards away from Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and his Virginia Military Institute cadets. Even though he was present at Brown’s hanging, Booth was never officially a private in the Richmond Grays. Instead of staying with the militia and formally enlisting, he continued his acting career after the incident.

It is unknown when and how the Marylander adopted his pro-slavery views, though it is believed that an 1851 incident had a profound effect on the young actor.

In 1849, Abraham Johnson, a free black man, had obtained some stolen wheat from a slave belonging to Edward Gorsuch, a farmer from Glencoe, Maryland. When charges were filed, Johnson and four of Gorsuch’s slaves – George Hammond, Joshua Hammond, Nelson Ford and Noah Buley – fled to nearby Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Two years later, Gorsuch received reports of the whereabouts of his property, the four slaves. On September 9, 1851, he appeared before Edward Ingraham, United States Commissioner, requesting arrest warrants for his four slaves, in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act that was passed a year earlier. Ingraham issued the warrants and authorized Deputy U.S. Marshal Henry H. Kline, who had a reputation in capturing fugitive slaves, to make the arrests.

In 1849, Abraham Johnson, a free black man, had obtained some stolen wheat from a slave belonging to Edward Gorsuch, a farmer from Glencoe, Maryland. When charges were filed, Johnson and four of Gorsuch’s slaves – George Hammond, Joshua Hammond, Nelson Ford and Noah Buley – fled to nearby Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Two years later, Gorsuch received reports of the whereabouts of his property, the four slaves. On September 9, 1851, he appeared before Edward Ingraham, United States Commissioner, requesting arrest warrants for his four slaves, in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act that was passed a year earlier. Ingraham issued the warrants and authorized Deputy U.S. Marshal Henry H. Kline, who had a reputation in capturing fugitive slaves, to make the arrests.

The slaves were found on the property of William Parker, a former slave and member of the Lancaster Black Self-Preservation Society. Kline and Gorsuch and seven others received resistance from Parker and his men while executing the warrants on September 11. Tempers flared and Edward Gorsuch’s son, Dickinson, said, “Father, will you take all this from a nigger?” An insulted Parker threatened to knock the younger Gorsuch’s teeth into his throat. Dickinson Gorsuch fired his gun in anger and was shot by Alexander Pinckney numerous times.

A fight between the two factions ensued that left Edward Gorsuch dead, and Dickinson Gorsuch, who was left for dead, was severely wounded. Some historians believe that there were only a dozen participants while others claim that there were up to forty people involved. Thirty-eight people were charged with treason because of the incident, but only one, a white neighbor named Castner Hanway, who was incorrectly identified as the leader of the resistance, was put on trial. The jury acquitted Hanway after only fifteen minutes of deliberations. Parker, Johnson and Pinckney fled to Canada, where they established new lives in Chatham, Ontario, a few hours away from Detroit, Michigan. Pinckney returned to the United States and enlisted as a Sergeant in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry on March 27, 1863, where he served for two years and was mustered out.

A fight between the two factions ensued that left Edward Gorsuch dead, and Dickinson Gorsuch, who was left for dead, was severely wounded. Some historians believe that there were only a dozen participants while others claim that there were up to forty people involved. Thirty-eight people were charged with treason because of the incident, but only one, a white neighbor named Castner Hanway, who was incorrectly identified as the leader of the resistance, was put on trial. The jury acquitted Hanway after only fifteen minutes of deliberations. Parker, Johnson and Pinckney fled to Canada, where they established new lives in Chatham, Ontario, a few hours away from Detroit, Michigan. Pinckney returned to the United States and enlisted as a Sergeant in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry on March 27, 1863, where he served for two years and was mustered out.

During the September 11, 1851 “Christiana Riot,” John Wilkes Booth was a student at the Milton Academy in Sparks, Maryland. The school was approximately one mile from the Gorsuch Farm. Booth’s best friend was Tommy Gorsuch, the youngest son of Edward.

In December 1860, Booth drafted a speech which he planned to deliver in Philadelphia. Whether he delivered the speech is unknown as it was discovered by his brother, Edwin, in a trunk of John Wilkes Booth’s belongings. In the final paragraph of the original manuscript that survived, he recounted his friendship with Tommy Gorsuch and lamented the loss of his playmate’s father.

During the war’s first years, as the Confederate forces mounted victories against a sluggish Union Army, Booth continued acting and was a quiet rebel sympathizer. After Confederate defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, his mood began to change.

Confederate Brigadier General Bradley Tyler Johnson planned to capture President Lincoln in the summer of 1864. Johnson, a Marylander, didn’t exactly keep the news secret, though the attempt was aborted. Booth probably heard about it from friends who had served under Johnson. When Booth planned his capture, the goal was to kidnap President Lincoln while the president was en route to the Old Soldiers Home and smuggle him to Richmond in order to facilitate the prisoner exchanges that General Grant halted. He planned the abduction with the help of George Atzerodt, who owned a carriage repair shop in Port Tobacco, Maryland; David Herold, a pharmacist’s assistant from Georgetown; Lewis Powell, who served in Mosby’s Rangers and the Confederate Secret Service; Samuel Arnold, a former classmate of Booth’s at St. Timothy Military Academy; Michael O’Laughlen, a lifelong friend of Booth; John Surratt, a Confederate courier and spy who was introduced to Booth through Dr. Samuel Mudd; and Mary Surratt, owner of the Surratt Tavern in Surrattsville (now Clinton), Maryland.

Confederate Brigadier General Bradley Tyler Johnson planned to capture President Lincoln in the summer of 1864. Johnson, a Marylander, didn’t exactly keep the news secret, though the attempt was aborted. Booth probably heard about it from friends who had served under Johnson. When Booth planned his capture, the goal was to kidnap President Lincoln while the president was en route to the Old Soldiers Home and smuggle him to Richmond in order to facilitate the prisoner exchanges that General Grant halted. He planned the abduction with the help of George Atzerodt, who owned a carriage repair shop in Port Tobacco, Maryland; David Herold, a pharmacist’s assistant from Georgetown; Lewis Powell, who served in Mosby’s Rangers and the Confederate Secret Service; Samuel Arnold, a former classmate of Booth’s at St. Timothy Military Academy; Michael O’Laughlen, a lifelong friend of Booth; John Surratt, a Confederate courier and spy who was introduced to Booth through Dr. Samuel Mudd; and Mary Surratt, owner of the Surratt Tavern in Surrattsville (now Clinton), Maryland.

When the prisoner exchanges resumed in January 1865, O’Laughlen and Arnold backed out of the plot. Booth let them leave because he understood that the rules of evidence in the court system at that time would make it difficult for them to discuss his plot with authorities. He was already seen with them in public, sent them notes, had them make deliveries for him. Essentially they became guilty by association.

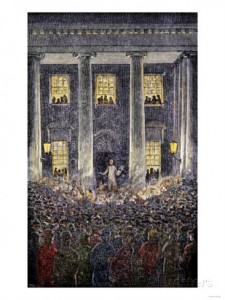

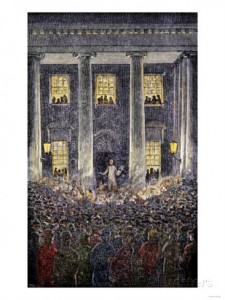

The plot changed on the night of April 11, 1865, when President Lincoln gave a speech announcing that he was in favor of granting suffrage to former slaves. Booth and Herold both attended the speech and made their way to the front of the crowd. President Lincoln said, “We encourage the hearts, and never the arms of twelve thousand to address their work, and argue for it, and proselyte for it, and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man, too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by having the already advanced steps toward it, than by running backward over them?” Booth fumed to Herold, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through.” He and Herold then pushed their way out of the crowd.

The plot changed on the night of April 11, 1865, when President Lincoln gave a speech announcing that he was in favor of granting suffrage to former slaves. Booth and Herold both attended the speech and made their way to the front of the crowd. President Lincoln said, “We encourage the hearts, and never the arms of twelve thousand to address their work, and argue for it, and proselyte for it, and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man, too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by having the already advanced steps toward it, than by running backward over them?” Booth fumed to Herold, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through.” He and Herold then pushed their way out of the crowd.

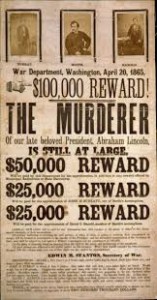

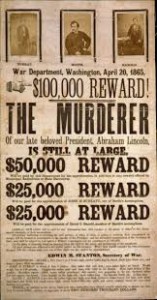

When he picked up his mail at Ford’s Theatre three days later, Booth discovered that President Lincoln and General Grant would be in attendance at the theater that night. Knowing that he had opportunity, he met with Herold, Powell, Atzerodt and Mary Surratt that afternoon and handed out the assignments. Atzerodt would take out Vice President Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel; Powell would assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward; Herold was to assist with their escape to southern Maryland and Virginia; Surratt was to ensure that carbines were ready for them at the tavern; and Booth would take out Lincoln himself.

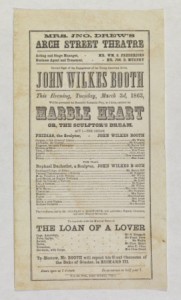

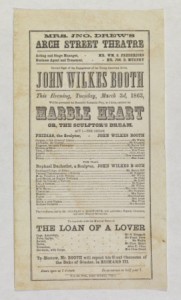

He was well known at Ford’s Theatre and performed in front of Lincoln there on November 9, 1863, during a production of The Marble Heart. The president frequently attended theatrical productions as his escape from the White House and the rigors of the war, so it was not as much of a surprise that Booth and Lincoln would meet there one final time.

He was well known at Ford’s Theatre and performed in front of Lincoln there on November 9, 1863, during a production of The Marble Heart. The president frequently attended theatrical productions as his escape from the White House and the rigors of the war, so it was not as much of a surprise that Booth and Lincoln would meet there one final time.

That evening, Mary Surratt successfully arranged to have the carbines brought to the Surratt Tavern. John Surratt was in Elmira, New York and did not participate. Powell attempted to assassinate Seward, whose life was spared because of a neck brace the secretary wore after a carriage accident that happened near Ford’s Theatre previously. Atzerodt spent the evening in the Kirkwood Hotel bar and got drunk instead of carrying out his assignment.

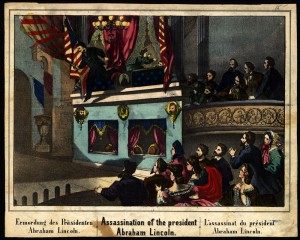

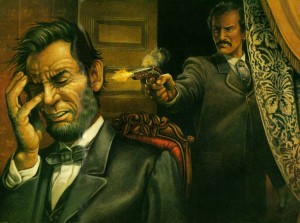

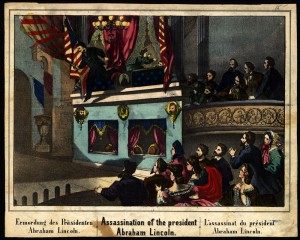

At 10:15 P.M., halfway through Act III Scene 2 of Our American Cousin, Asa Trenchard, a character played by Harry Hawk, uttered the line, “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Wal, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal – you sockdologizing old man-trap!” As the audience erupted in laughter, John Wilkes Booth fired a .41 caliber round ball from a .44 caliber derringer through the back of President Lincoln’s head from just inches away, close enough to leave powder burns on the back of the president’s skull.

Booth leaped from the Presidential Box to the main stage, a distance of eleven feet, catching his boot spur in one of the two U.S. Treasury Department flags during the fall. He ran past Hawk to a waiting light bay mare with an uneasy temperament that was held by Joseph “Peanuts” Burroughs, a young stagehand employed by Ford’s Theatre. Booth struggled with the startled animal, flung himself over the saddle, gained control of the horse and galloped through the alley behind the theatre on to F Street. The manhunt for the assassin began.

Booth leaped from the Presidential Box to the main stage, a distance of eleven feet, catching his boot spur in one of the two U.S. Treasury Department flags during the fall. He ran past Hawk to a waiting light bay mare with an uneasy temperament that was held by Joseph “Peanuts” Burroughs, a young stagehand employed by Ford’s Theatre. Booth struggled with the startled animal, flung himself over the saddle, gained control of the horse and galloped through the alley behind the theatre on to F Street. The manhunt for the assassin began.

In his diary, Booth wrote that he yelled “Sic Semper Tyrannis,” Latin for “Thus Always to Tyrants,” the Virginia State Motto, just before he shot the president. Most of the eyewitnesses claim that he yelled the Latin phrase after he jumped to the stage while others claim that he yelled the phrase after shooting Lincoln and before jumping. Booth is the only one who claims that he uttered the phrase even before shooting the president.

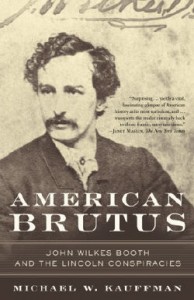

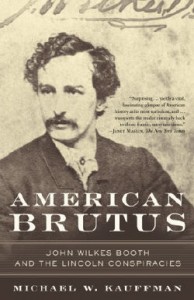

It was also widely reported, largely because of Booth’s diary entry, that the assassin broke his leg during the jump. Historian Michael W. Kauffman, author of American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, is of the opinion that Booth, long known for his aggressive and athletic performances, broke his leg in a riding accident between his crossing of the Navy Yard Bridge and his arrival at Surratt’s Tavern in Surrattsville.

It was also widely reported, largely because of Booth’s diary entry, that the assassin broke his leg during the jump. Historian Michael W. Kauffman, author of American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, is of the opinion that Booth, long known for his aggressive and athletic performances, broke his leg in a riding accident between his crossing of the Navy Yard Bridge and his arrival at Surratt’s Tavern in Surrattsville.

Booth and Herald had switched horses by then. Sergeant Cobb and others were positive that Booth had ridden away on a bright bay mare, and everyone agreed that Herold was on a roan. But outside the city, everyone who encountered them remembered it the other way around. In light of Booth’s broken leg, the switch made perfect sense. An injured man would certainly have preferred the gentle, steady gait of a horse like the one Herold had rented. From Lloyd’s to Mudd’s, Booth stayed on that horse, and Herold rode the mare, who was now noticeably lame, with a bad cut on her left front leg. Clearly, she had been involved in an accident.

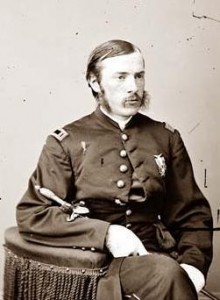

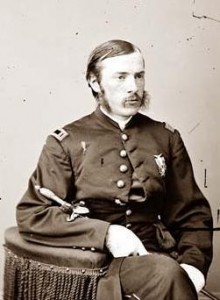

Dr. Charles Leale, Lincoln’s attending physician at Ford’s Theater

As for President Lincoln, the first doctor to attend to him was twenty-three year old Dr. Charles Leale, who became the attending physician during the ordeal. Leale checked the president’s pulse. Finding none, he had Lincoln moved from the chair to the floor where he examined his patient for stab marks. He found the bullet hole instead. Leale noticed that whenever he moved his hand away from the blood clot that formed in the opening of the president’s skull, the blood flowed freely and Lincoln’s breathing was better.

Under the suggestion of Dr. Charles Taft, who came to the Presidential Box to assist, and with the concurrence of Dr. Leale, it was agreed to move President Lincoln to the nearest house instead of the White House. Six soldiers carried the president down the narrow stairwell and out of the theatre to the nearest house, a boarding house at 453 Tenth Street, directly across from Ford’s Theatre, that was owned by Mr. William Petersen. The soldiers moved the president to a room that was rented by William T. Clark, a War Department employee who was not home at the time. The six foot four Lincoln was too long for the bed, so the footboard was removed and the president was placed diagonally across the mattress so he would fit.

On March 16, less than a month before the assassination, Booth visited an acquaintance, John T. Mathews, a Ford’s Theatre stock company actor who happened to play Mr. Coyle during the fateful performance of Our American Cousin. When Mathews arrived, Booth was sprawled across the bed waiting for his friend. This allegedly is the same bed to which President Lincoln was taken on the night of April 14.

Dr. Leale, with the assistance of Drs. Robert King Stone, Charles Sabin Taft, Albert King, Joseph K. Barnes, Charles Henry Crane and Anderson Ruffin Abbott attended to the President while Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ran the government and directed the hunt for Booth from the boarding house room.

***

While the doctors maintained a vigil over the president, his condition was not improving. “At this time my knowledge of physiology, pathology and psychology told me that the President was totally blind as a result of blood pressure on the brain, as indicted by the paralysis, dilated pupils, protruding and bloodshot eyes, but all the time I acted on the belief that if his sense of hearing or feeling remained, he could possibly hear me when I sent for his son, the voice of his wife when she spoke to him and that the last sound he heard, may have been his pastor’s prayer, as he finally committed his soul to God,” said Dr. Leale while addressing the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States New York State Commandery in February 1909. Dr. Leale’s official report written in 1865 just hours after Lincoln’s death, and echoed by his 1909 address, was discovered in a collection at the National Archives in 2012.

***

President Lincoln passed away at 7:22 A.M. on Saturday, April 15, 1865. Rev. Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church offered a prayer, at Secretary of War Stanton’s urging. James A. Tanner, a War Department stenographer who recorded the events, reached for his pencil to write the prayer in shorthand. Unfortunately, the pencil lead broke and Gurley’s immortal words are lost to history. We also miss out on the immortal words of the War Secretary who is believed to have said, “Now he belongs to the ages.” Questions about today as to whether he said “ages,” “angels,” or even uttered anything at all. We will never know for sure what was said at that important time in history because of the breaking of one pencil lead.

President Lincoln passed away at 7:22 A.M. on Saturday, April 15, 1865. Rev. Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church offered a prayer, at Secretary of War Stanton’s urging. James A. Tanner, a War Department stenographer who recorded the events, reached for his pencil to write the prayer in shorthand. Unfortunately, the pencil lead broke and Gurley’s immortal words are lost to history. We also miss out on the immortal words of the War Secretary who is believed to have said, “Now he belongs to the ages.” Questions about today as to whether he said “ages,” “angels,” or even uttered anything at all. We will never know for sure what was said at that important time in history because of the breaking of one pencil lead.

***

Booth thought that he would be a great hero in the south for his deed, but soon found out that the southerners didn’t rejoice at the assassination of the president like he had hoped. He and David Herold evaded authorities for twelve days treacherous days in which he met with Dr. Samuel Mudd to have his leg set; walked through the Zekiah Swamp; crossed the Potomac twice by rowboat among a flotilla of naval vessels that were searching for him; slept in a slave quarters and had little to eat. The 16th New York Cavalry caught up to them at the farm of Richard Garrett near Bowling Green, Virginia. Booth and Herold were sleeping in Garrett’s tobacco barn when the cavalry arrived after one o’clock in the morning.

Booth thought that he would be a great hero in the south for his deed, but soon found out that the southerners didn’t rejoice at the assassination of the president like he had hoped. He and David Herold evaded authorities for twelve days treacherous days in which he met with Dr. Samuel Mudd to have his leg set; walked through the Zekiah Swamp; crossed the Potomac twice by rowboat among a flotilla of naval vessels that were searching for him; slept in a slave quarters and had little to eat. The 16th New York Cavalry caught up to them at the farm of Richard Garrett near Bowling Green, Virginia. Booth and Herold were sleeping in Garrett’s tobacco barn when the cavalry arrived after one o’clock in the morning.

Booth did not want to give himself up and a stand-off ensued. After the cavalrymen set fire to the barn he allowed Herold to surrender. Sometime around 3 A.M., Sergeant Boston Corbett, who had his carbine in the ready position through the gaps between the barn’s wooden slats, saw Booth raise a rifle. Corbett shot Booth in the neck. The assassin was now paralyzed and mortally wounded.

At first light on the morning of April 26, 1865, John Wilkes Booth, having been removed from the burning barn, told Luther Byron Baker, “Tell my mother – tell my mother that I did it for my country – that I die for my country.” A few minutes later, Booth looked at his paralyzed hands. Baker lifted them above the assassin’s face. “Useless. Useless,” were the last words uttered by John Wilkes Booth.

At first light on the morning of April 26, 1865, John Wilkes Booth, having been removed from the burning barn, told Luther Byron Baker, “Tell my mother – tell my mother that I did it for my country – that I die for my country.” A few minutes later, Booth looked at his paralyzed hands. Baker lifted them above the assassin’s face. “Useless. Useless,” were the last words uttered by John Wilkes Booth.

As the body of the fallen President lay in state at the Capitol, Mary Surratt was arrested and questioned regarding the conspiracy. She, along with David Herold, George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell were charged and convicted by a military commission for their roles in the plot. On July 7, 1865, all four were hanged for President Lincoln’s assassination.

However, questions have been raised as to whether it was John Wilkes Booth who was killed at the Garrett Farm.

In 1907, Finis L. Bates wrote, The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, which tells the story of Mr. John St. Helen, a Granbury, Texas man who admitted to being the Lincoln assassin. He made the confession to Bates in the 1870s, while St. John thought he was dying of a terminal illness. He left Granbury shortly after his recovery.

1931 photo of David George’s mummy.

In 1903, a man named David E. George, living in Enid, Oklahoma, admitted that he was John Wilkes Booth, and that he had changed his name from St. John. Shortly after the confession, George allegedly poisoned himself with arsenic. The arsenic reacted with the embalming fluids and the body was mummified. Bates identified the body as his former friend, St. John, and put the mummy on exhibit at carnival exhibitions around the country. It remained on tour until it disappeared in the 1970s.

Other theories about Booth’s escape abound. One story has it that Secretary of War Stanton arranged to have a Confederate named John W. Boyd brought up from a South Carolina prison, and that it is Boyd’s body that was recovered at the Garrett Farm. Booth is said to have been given an early warning and left the area before the cavalry arrived.

Another theory, as mentioned in a December 23, 2010 edition of Brad Meltzer’s Decoded on the History Channel, has Booth fleeing to India where he lived for another forty-one years and was sending payments home to his wife and children.

In an attempt to try to find out the truth, the descendants of the Booth family, including those who hold the 1869 certificate of ownership for the burial plot in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery, filed a petition with the Baltimore Circuit Court in 1995 requesting to have the remains of John Wilkes Booth exhumed.

Twenty-two of the Booth relatives supported the exhumation, including two as plantiffs, all hoping to find out whether the escape theory is the truth or a myth. The Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of Health and Medicine were two of the institutions where Booth’s remains would be examined by forensic scientists.

The case drew a high-powered panel of star historians to present the evidence. The petitioners brought up Dr. Douglas H. Ubelaker, a forensic anthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History; John E. Smialek, M.D., Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland; Dr. Paul Sledzik, a forensic anthropologist with the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Dr. Jean Baker, professor of history at Goucher College; Gus Russo, John F. Kennedy assassination investigator; and Nathaniel Orlowek, a John Wilkes Booth researcher and one of the original petitioners (he was removed as a petitioner at the request of the defendant). Green Mount Cemetery, the defendants in the case, also had an impressive lineup that included Dr. James Starrs, professor of law and forensic sciences at George Washington University School of Law; Steven Miller, a researcher who has examined the lives of the soldiers at the Garrett Farm; Dr. William Hanchett, professor of history- emeritus, San Diego State University; William C. Trimble Jr., president of Green Mount Cemetery; Michael W. Kauffman, a leading authority on the Lincoln Assassination and author of American Brutus; Dr. Terry Alford, professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College; and James O. Hall, one of the world’s foremost Lincoln Assassination experts.

The case drew a high-powered panel of star historians to present the evidence. The petitioners brought up Dr. Douglas H. Ubelaker, a forensic anthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History; John E. Smialek, M.D., Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland; Dr. Paul Sledzik, a forensic anthropologist with the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Dr. Jean Baker, professor of history at Goucher College; Gus Russo, John F. Kennedy assassination investigator; and Nathaniel Orlowek, a John Wilkes Booth researcher and one of the original petitioners (he was removed as a petitioner at the request of the defendant). Green Mount Cemetery, the defendants in the case, also had an impressive lineup that included Dr. James Starrs, professor of law and forensic sciences at George Washington University School of Law; Steven Miller, a researcher who has examined the lives of the soldiers at the Garrett Farm; Dr. William Hanchett, professor of history- emeritus, San Diego State University; William C. Trimble Jr., president of Green Mount Cemetery; Michael W. Kauffman, a leading authority on the Lincoln Assassination and author of American Brutus; Dr. Terry Alford, professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College; and James O. Hall, one of the world’s foremost Lincoln Assassination experts.

The petitioners sought to create a historical basis regarding whether Booth had escaped, while utilizing an exhumation and remains identification to determine whether or not they were those of John Wilkes Booth or some other person. Green Mount Cemetery, as the defendant, based their defense upon the documented positive identifications that existed from the time Booth died at the Garrett Farm until he was buried at Green Mount in June 1869.

Green Mount Cemetery believes they are the ones that John Wilkes Booth’s mother, Mary Ann Booth, entrusted to ensure that her son rests in peace. It is a contractual relationship between the cemetery and the Booth family that dates back to 1852 when the patriarch of the family, Junius Brutus Booth, was buried there. The cemetery board contends that it is from this contractual and trust relationship that they strive to “prevent distributing the remains of the deceased for frivolous unsubstantial reasons.”

After a four-day trial in May 1995, Judge Joseph H.H. Kaplan denied the petition in Kline v. The Green Mount Cemetery. In his judgment, Kaplan wrote:

To summarize, the alleged remains of John Wilkes Booth were buried in an unknown location some one hundred twenty-six (126) years ago and there is evidence that three infant siblings are buried on top of John Wilkes Booth’s remains, wherever they may be. There may be severe water damage to the Booth burial plot and there are no dental records available for comparison. Thus, an identification may be inconclusive. A distant relative is seeking exhumation and any exhumation would require that the Booth remains be kept out of the grave for an inappropriate minimum of six (6) weeks. The above reasons coupled with the unreliability of Petitioners’ less than convincing escape/cover up theory gives rise to the conclusion that there is no compelling reason for exhumation.

Mark S. Zaid, the Booth family attorney, said, “Everybody is very disappointed. The whole object was to try and allow the truth to prevail over myth. I have my doubts whether this decision will do anything to dispel the story.”

In May 1996, Zaid filed an appeal with the Special Court of Appeals requesting either the exhumation take place or a new trial ordered with specific instructions to the judge on proper legal standards. In the court filing, Zaid said that Judge Kaplan permitted the Green Mount officials an improper degree of intervention in the trial because a cemetery cannot block an exhumation if it’s requested by the family.

When the three-judge panel made its ruling, it cited numerous historical examples of John Wilkes Booth’s body identification by people who knew him; concurred with Judge Kaplan that the cemetery had the right to intervene based upon legal precedent; and ruled against the family. “For the reasons noted, we conclude that Judge Kaplan did not err in dismissing the amended petition,” the ruling said. “He properly allowed Green Mount Cemetery to participate actively in the case; his factual conclusions were supported by substantial evidence; his legal conclusions were correct; and the judgment call he made was entirely appropriate.”

Edwin Booth

With advances in science in the collection and analysis of DNA, the Booth family may try another route. The direct descendants of Edwin Booth have given their approval to exhume his remains to extract a DNA sample. The National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. has three cervical vertebrae, taken from the Garrett Farm body, that the family is hoping contains enough extractable DNA to prove or disprove the conspiracy theories.

The fact that John Wilkes Booth killed President Abraham Lincoln is indisputable. Whether Booth himself was killed at the Garrett Farm or made his escape to India, Texas, Oklahoma or parts unknown is still up for debate, though a vast majority of historians accept the version that he was killed by Sergeant Corbett and later buried in Green Mount Cemetery.

[Source: Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War by Jeffrey S. Williams] (Used with permission)

Click here for a list of additional Lincoln Assassination resources.