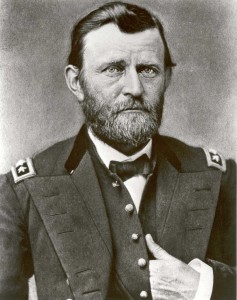

Born Hiram Ulysses Grant, he unprotestingly accepted the clerical error changing his name to Ulysses Simpson Grant when he entered West Point in 1839. His new name, U.S. Grant, lent itself to his Old Army nickname, Uncle Sam Grant, or simply Sam Grant, and to his Civil War nickname, Unconditional Surrender Grant. Such names symbolize Grant: as a soldier, his loyal patriotism and relentless pursuit of victory; yet as a man, his unchallenged acceptance of a bureaucratic blunder changing his identity rather than risk his opportunity for advancement.

Advancement at first appeared unlikely for this eldest child of Jesse Root Grant and Hannah Simpson Grant. Born 27 April 1822 in Point Pleasant, Ohio, and raised in Georgetown, Ohio, he grew up in modest circumstances that hardly portended his future greatness. However, opportunity rose in 1839, when his ambitious father obtained for him appointment to the U.S. Military Academy as the best means to get a good education for free.

Grant’s years at West Point proved solid but not outstanding. He excelled only in horsemanship, reflecting his lifelong love of animals, but he worked sufficiently diligently in his studies and deportment to rank midway in his class. Out of sixty-three cadets entering the Military Academy in 1839, he placed twenty-first among the 39 who actually graduated in 1843. More important than his studies or standing were his ability to master the rigors of discipline and education, his exposure to a wider world than small-town Ohio, and his friendship with classmates who became comrades during the Civil War, especially Rufus Ingalls, Isaac Quinby and Frederick Steele. Evidence also suggest that, even when General-in-Chief, he continued according undeserved admiration to the head of his Class of 1843, William B. Franklin.

Two other cadets with whom he enjoyed not only life-long friendship but also family ties were James Longstreet, Class of 1842, his future wife’s cousin; and Frederick Dent, grant’s own roommate and his future brother-in-law. Grant met Dent’s sister Julia in 1843 while serving as a second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry Regiment at Jefferson Barracks, south of St. Louis. Grant soon began courting Julia, and on 22 August 1848 they married. Four children were born to their union: Frederick, 1850; Ulysses Jr., 1852; Ellen, 1855; and Jesse, 1858. Sam and Julia remained in love for the rest of their lives. she would prove an inspiration during his introduction to warfare in Mexico, a comfort during low points of his life, a reassurance during the trials of senior leadership, and a helpmeet to whom he could unburden himself openly and unreservedly.

By the time they married, Grant had experienced war. In May 1844, his regiment transferred from Missouri to Natchitoches, Louisiana, then America’s southwestern frontier. After Texas joined the Union, the 4th Infantry became part of Zachary Taylor’s army at Corpus Christi Grant, who always admired Taylor’s “rough and ready” ways, participated in that general’s splendid victories at Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey. Transferred with most Regular regiments to the army of Winfield Scott, whom he respected but did not like, Grant fought in the great campaign from Vera Cruz to Mexico City. These operations earned him brevets as first lieutenant for Molino del Ray and as captain for Chapultepec, and he received the substantive rank of first lieutenant as of 16 September 1847, two days after the enemy capital fell.

Politically, Grant opposed war with Mexico. Militarily, however, the Mexican War proved critical to his soldierly development. It showed him that battlefields were horrid yet survivable. It demonstrated how using the tactical and strategic initiative could dominate an enemy, even deep in enemy territory. and, equally importantly, it made him appreciate the critical importance of logistics. as regimental quartermaster of the 4th Infantry from camargo until the Americans evacuated Mexico in 1848, and again from November 1848 to August 1853, he gained experience and understanding of supplying troops in wartime and peacetime. Such understanding set him apart from so many other Civil War generals, whose grandiose concepts of grand strategy collapsed for lack of logistical undergirding.

Following the Mexican-American War and marriage, Grant served with his regiment at East Pascagoula, Mississippi; Fort Wayne, Michigan; and Madison Barracks, New York. Then in 1852 the 4th Infantry transferred to the Pacific Coast, where Grant eventually served at Fort Humboldt, California. The transfer brought promotion to captain on 5 August 1853. It also necessitated separation from his beloved Julia. Separation, isolation, and lack of prospects for future promotion weighed heavily on grant. Like many other Regular officers, before and after the Civil War, he turned to the bottle. Drinking further depressed morale and performance. On 31 July 1854, he resigned from the Army under a cloud. To help pay his fare back to Missouri, he had to rely on the generosity of his fellow officer and friend since West Point, Simon Bolivar Buckner.

Missouri brought him reunion with Julia but not success. He merely eked out an existence farming at Hard Scrabble near the Dent plantation, White Haven, and he was denied a coveted county job. In 1860, economic straits and increasing uneasiness with secessionist St. Louis made him move to Galena, Illinois, to work as a clerk in his father’s leathergoods store.

From cadet to captain to clerk, Sam Grant had risen from obscurity on the Ohio River to serve his country well from the Rio Grande to Mexico City, but now he was sinking back into oblivion on the upper Mississippi. Had he died in 1860, he would rate no more than a footnote in Mexican-American War histories and a brief paragraph in West Point alumni directories.

The Civil War rescued Grant from such anonymity and afforded him opportunity to earn the highest military and civil offices the United States can bestow. Context and circumstance created that opportunity, but it was Grant’s abilities both innate and acquired, which enabled him to succeed in a war where so many officers with far more illustrious records at West Point and in the Old Army would fall short.

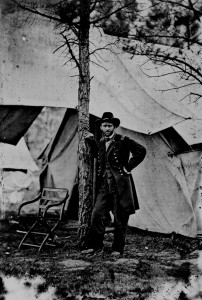

Some of those officers suffered the disadvantage of immediate elevation to high command in 1861. Grant, in contrast, worked upward from modest beginnings. His first service came as Galenans selected him to preside over a patriotic meeting when war erupted. He declined command of Galena’s company (later Company F/12th Illinois Infantry Regiment), but he did train that outfit. he also accepted Governor Richard Yates’s appeal to make his experience available to the state Adjutant General in raising and organizing Illinois’ first sixteen regiments. The national government proved less interested in Grant, as both the War Department and George B. McClellan, commanding the Department of the Ohio, ignored his offers of service in May. Again, it was Yates who recognized Grant’s ability. On 15 June 1861, the governor appointed him colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry at Springfield. Grant promptly shaped up that refractory regiment. On 28 June, he and the unit were mustered into Federal service. Within days, the 21st was deemed ready to go to war. But was Grant himself ready?

In the summer of 1861, Kentucky’s neutrality skewed the Western theater into borderland operations in western Virginia and Missouri. Ohio and Indiana troops covered the Appalachian sector. It fell to Illinois and Iowa to secure Missouri. Grant’s regiment was ordered to Quincy on 3 July. Nine days later, it crossed into Missouri to help guard the Pacific Railroad. General Thomas A. Harris’s pro-Secessionist Missouri State guard division threatened the railroad. On 17 July, Grant advanced against Harris at Florida on the Salt River. Grant had fought in many battles in Mexico but always as a subaltern. This was his first operation as commander, and the responsibility of command weighed heavily upon him.

“As we approached…Harris’ camp…,” Grant later remembered, “my heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on. when we reached a point from which the valley below was in full view I halted. The place where Harris had been encamped a few days before was still there…but the troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards. From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.”

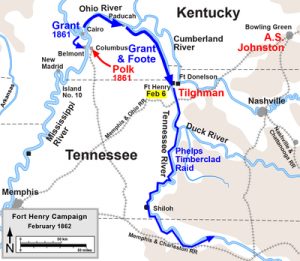

Due not so much to this victory at Salt River as to influential Congressman Elihu b. Washburne of Galena, who would prove a continuing benefactor, Grant was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers on 31 July, ranking from 17 May. He briefly commanded at Ironton, Jefferson City, and Cape Girardeau. On 1 September, he took charge of the District of Southeast Missouri, including southern Illinois, headquartered at Cairo. This new responsibility put him in position to confront the Confederate invasion of Kentucky, which ended that state’s neutrality. Without awaiting authorization, Grant boldly countered by occupying Paducah on 6 September, thus forestalling Southern efforts to seize the mouth of the Tennessee River.

Such boldness recurred almost as rashness, as on 7 November, when he led five regiments down the Mississippi against the camp at Belmont, Missouri. Grant overran the camp but was lucky to escape before reinforcements from the nearby Confederate stronghold of Columbus, Kentucky, could intercept him. Despite its limited achievements, the Belmont foray shone forth amid a series of Union defeats that summer and autumn. It marked Grant as one commander who did not insist on perfection but who was willing to advance with the resources at hand.

The Belmont expedition proved only the first of Grant’s many operations along navigable western rivers. In early February, he led two divisions up to the Tennessee River against Fort Henry. The nearly flooded fort surrendered to the cooperating Federal navy on 6 February, before the army could engage. Grant then boldly moved overland against Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Although the Graycoats repulsed Union warships on 14 February and nearly rolled up Grant’s right on 15 February, he contained their river breakout and captured some trenches. In a cowardly collapse of will, the two senior Southern commanders fled. On 16 February, the ranking remaining officer, Simon B. Buckner - Grant’s Old Army friend - asked for terms of capitulation. “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted,” replied Grant; “I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Rather than face further assault, Buckner surrendered approximately 17,000 men.

Losing Forts Henry and Donelson broke the Confederate defense line in Kentucky, doomed Nashville, and forced the military frontier back to the Memphis-Corinth-Chattanooga line. Those victories instantly made Grant a national hero and gave him the nickname Unconditional Surrender Grant. It also brought promotion to major general of volunteers, as of 16 February. By mid-March he was the senior subordinate in the Western theater under overall commander Henry W. Halleck. Along with new rank came a new name for his command. Technically, he operated against Henry and Donelson while heading the District of Cairo, as his expanded territory had been known since 23 December. On 17 February, however he assumed command of the new District of West Tennessee, “limits not defined.” In eventually defining its limits as the district expanded into the Army of the Tennessee, grant would create one of the great combat forces of American history.

That army and its achievements lay in the future. Grant barely survived that long, indeed barely lasted beyond his February triumphs. When Grant visited occupied Nashville Halleck unjustly suspected that he was abandoning his command to resume drinking. General-in-Chief McClellan uncritically authorized Halleck to arrest or relieve Grant. Halleck would not go that far, but on 4 March he ordered Grant to remain at Fort Henry and to turn over to Charles F. Smith command of the field army then preparing to advance up the Tennessee River. Smith had been commandant of cadets while Grant was at West Point and had led a light battalion with great distinction in 1847. Many officers, including Grant, thought Smith was worthy of army command.

Yet Grant was severely struck by such a slur so soon after his splendid successes and sought to be sent from Halleck’s department. The senior soldier, however, relented and restored him to command of the field army on 11 March. By the time the Illinoisan rejoined his forces on 17 March, smith was fatally ill and would die on 25 April. Both Grand and the Union would miss the old hero in upcoming operations.

The army had now grown from three divisions at Donelson to six. Five divisions concentrated at Pittsburg Landing on the west bank of the Tennessee, preparing to attack the key rail junction at Corinth, Mississippi. The remaining division stayed farther north. Grant’s own headquarters, too, were downriver. Immediate command at Pittsburg Landing rested with William T. Sherman who had headed the District of Cairo during Donelson and who was now beginning decades of service and friendship with Grant.

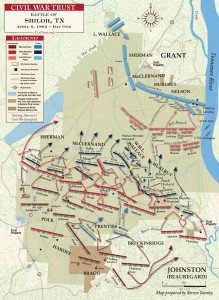

Neither Grant nor Sherman fortified the landing. They thought primarily of attacking Corinth once Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio arrived from Nashville. However, Albert Sidney Johnston’s Butternuts planned to strike first. He not only reconcentrated his troops from Kentucky but also summoned reinforcements from the Gulf coast and Arkansas. Without awaiting the Trans-Mississippi column, Johnston attacked on 6 April. Desperate fighting drove Union troops from their camps back toward the Tennessee River. Grant arrived during the battle to help rally his men. Equally important was the arrival of Buell’s vanguard. The next day, Grant led the combined armies counterattacking. The exhausted Confederates eventually withdrew to Corinth, leaving Grant holding the field.

This battle of Shiloh was the largest, bloodiest battle in American history up to then. It awoke both nations to the reality of war and to each side’s commitment to its cause. Both Grant and Sherman bristled at charges of being taken by surprise. Tactically, they were not surprised. But unquestionably, they were caught off guard, strategically. They so focused on their own preparations to gain yet another victory at Corinth that they did not take account of Confederate capability to concentrate and counterattack. Southern misdeployments and miscalculation, Johnston’s death, Federal forces’ bravery, and Grant’s own determination not to flee but to fight back and to counterattack on 7 April, all cost Graycoats, but to their great gamble, and enabled Yankees to claim at least limited success. In reflecting upon the battle decades later, Grant wrote that “The troops on both sides were American, and united they need not fear any foreign foe It is possible that the Southern man started in with a little more dash than his Northern brother but he was correspondingly less enduring.”

Halleck reached Pittsburg Landing on 11 April and assumed direct command of the “gray group” threatening Corinth (Army of the Ohio, Army of the Tennessee, and soon John Pope’s Army of the Mississippi. Grant became second-in-command, an office without responsibility, and his beloved army of the Tennessee passed to George H. Thomas - a change perhaps explaining Grant’s enduring resentment of Thomas. Grant played virtually no role in Halleck’s sluggish campaign that finally occupied Corinth on 30 May. That figurehead status proved to galling that Grant considered taking prolonged leave just to get away. Fortunately for the Union, Sherman and Halleck persuaded him to remain.

Halleck reached Pittsburg Landing on 11 April and assumed direct command of the “gray group” threatening Corinth (Army of the Ohio, Army of the Tennessee, and soon John Pope’s Army of the Mississippi. Grant became second-in-command, an office without responsibility, and his beloved army of the Tennessee passed to George H. Thomas - a change perhaps explaining Grant’s enduring resentment of Thomas. Grant played virtually no role in Halleck’s sluggish campaign that finally occupied Corinth on 30 May. That figurehead status proved to galling that Grant considered taking prolonged leave just to get away. Fortunately for the Union, Sherman and Halleck persuaded him to remain.

Grant’s situation improved over the summer as Halleck and Pope went to Washington and as Buell advanced against Chattanooga, taking Thomas with him. Three of Pope’s other two divisions under William S. Rosecrans remained with Grant who resumed direct command of his District of West Tennessee. Grant’s mission was defensive: guarding Federal conquests of the past twelve months, from Paducah and Columbus to Corinth and Memphis. When Sterling Price’s Butternuts passed through the region toward Middle Tennessee, Grant struck them at Iuka, but they repulsed Rosecrans and escaped on 19 September. Two weeks later, Price and Earl Van Dorn pounced on Rosecrans at Corinth. The Yankees saved the city, but the secessionists eluded Grant’s efforts to intercept their retreat.

Standing on the defensive would never conquer the Confederacy and risked losing earlier gains. In autumn, federal armies from Virginia to Missouri resumed advancing. Grant’s mission was to move southward along the Mississippi Central Railroad against Jackson, thence westward against Vicksburg. His command was designated the Department of the Tennessee on 16 October, and either days later it was named the XIII Corps. Calling an army of ten divisions one corps was incongruous. The addition of four more divisions in December made that appellation even more inept. On 18 December, the War Department ordered the Army of the Tennessee divided into the XIII, XV, XVI, and XVII Corps. Two divisions each from Arkansas, Missouri, and Kentucky joined Grant in 1863. at the height of the Vicksburg campaign, his field army contained sixteen divisions, and six other divisions served elsewhere in his department.

Such force increases reflected the growing success of Grant’s Vicksburg campaign. Those operations, however, began badly The farther he penetrated along the Mississippi Central Railroad, the more vulnerable his supply line became. When Van Dorn’s and Bedford Forrest’s cavalry cut those communications in December, Grant had to abandon his overland campaign and withdraw to Memphis. In doing so, he learned to live off the land, without formal supply lines and depots. He would use that experience well in later operations against Vicksburg.

Sherman’s repulse at Chickasaw Bayou, 27-29 December, and the advent of Grant’s former subordinate and enduring rival John A. McClernand to command the drive down the Mississippi led Grant himself to take charge of all forces on both banks of that river, including McClernand’s. Grant spent early 1863 in four fruitless attempts to reach firm ground east of Vicksburg. Finally, in mid-April, the U.S. Navy, with which Grant always maintained effective cooperation, ran the Vicksburg batteries. His army then marched down the Louisiana side of the river, and on 30 April, the navy began ferrying the forces to the left bank. “When this was effected,” Grant later recalled, “I felt a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since…I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.”

On dry ground at last, Grant then conducted one of the most brilliant strategic campaigns in American military history. First, he defeated local Butternut defenders at Port Gibson on 1 May. Then he turned east and dispersed Confederate reinforcements gathering near Jackson on 12-14 May. Next, he struck back westward, routing the main Southern army on 16-17 May, and drove it into Vicksburg. his two assaults failed on 19 and 22 May, but he relentlessly besieged the city, while providing Sherman sufficient force to counter Confederates reassembling at Jackson. On 4 July, Vicksburg’s army of four divisions surrendered. Five days later, the last Secessionist position on the Mississippi also capitulated. As President Lincoln said, “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” Achieving this great result, so vital to Midwesterners and so crippling to Southerners, brought Grant promotion to major general in the Regular Army, ranking from 4 July, and assured his place in American history.

Sherman then chased away the small Confederate army in Jackson. grant wanted to attack Mobile promptly, but General-in-Chief Halleck again scattered the large army, just as after Corinth. Seven divisions were diverted to Kentucky, Arkansas, and West Louisiana, and Grant’s remaining forces went on the defensive. The general himself recuperated from a severe injury while visiting New Orleans.

Grant did not long remain idle. He already ranked as the most successful Federal general of the war. Washington again turned to him after disaster struck Rosecran’s army at Chickamauga on 19-20 September. On 18 October, Grant was assigned to command the new Military Division of the Mississippi, embracing the entire Western theater from teh Appalachians to the Mississippi. he promptly removed his rival Rosecrans and then concentrated on relieving besieged Chattanooga. Four divisions from his own army, now under Sherman, and four divisions from Virginia under Joseph Hooker reinforced Thomas’s beleaguered Army of the Cumberland. Hooker promptly opened better supply routes into the city. In late November, Grant broke out at Orchard Knob, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge, sending the routed Secessionists streaming into Georgia. He then dispatched Sherman to relieve the Army of the Ohio in Knoxville, saving that city, too.

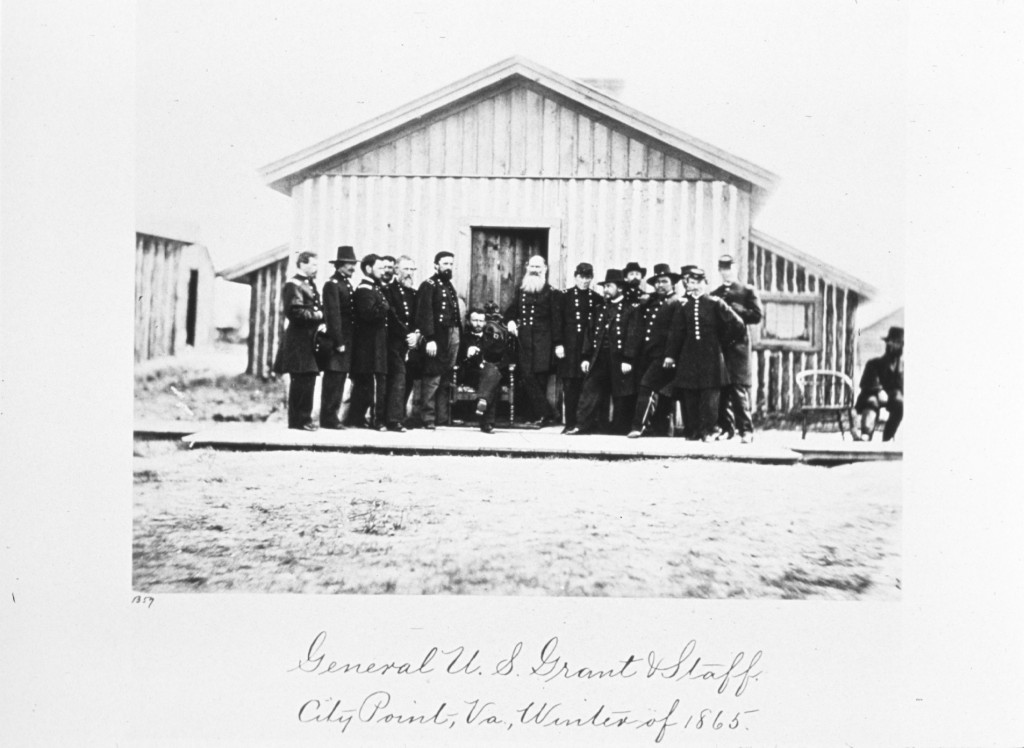

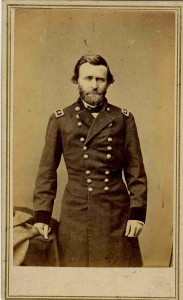

Henry, Donelson, Shiloh, Corinth, Vicksburg, now Chattanooga and Knoxville - everywhere Grant had gained tactical success, usually accompanied by profound strategic success which secured federal conquests, dealt devastating blows to the Confederacy, and netted many Southern prisoners. No Butternut army or general in the West could withstand him. Only one Confederate army and general continued enjoying success. Grant had earned the right to challenge that army and that commander. On 10 March 1864, he was promoted to general-in-chief of all federal armies with the rank of lieutenant general (dating from 2 March), the first American officer holding that grade since George Washington in 1798-1799. Unlike Halleck, Grant would not make this a desk job. Unlike Sherman, grant would not insist on remaining in the West. The Illinoisan understood his place and his mission: the Eastern theater with his “headquarters, armies in the field,” fighting to the death with General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

Henry, Donelson, Shiloh, Corinth, Vicksburg, now Chattanooga and Knoxville - everywhere Grant had gained tactical success, usually accompanied by profound strategic success which secured federal conquests, dealt devastating blows to the Confederacy, and netted many Southern prisoners. No Butternut army or general in the West could withstand him. Only one Confederate army and general continued enjoying success. Grant had earned the right to challenge that army and that commander. On 10 March 1864, he was promoted to general-in-chief of all federal armies with the rank of lieutenant general (dating from 2 March), the first American officer holding that grade since George Washington in 1798-1799. Unlike Halleck, Grant would not make this a desk job. Unlike Sherman, grant would not insist on remaining in the West. The Illinoisan understood his place and his mission: the Eastern theater with his “headquarters, armies in the field,” fighting to the death with General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

To attack Lee and the Confederate power center, Virginia, Grant developed a dual approach. Grand strategically, he concerted all Union armies to strike simultaneously. “There were…seventeen distinct [Yankee] commanders,” Grant later wrote. “Before this time these various armies had acted separately and independently of each other, giving the enemy an opportunity often of depleting one command, not pressed, to reinforce another more actively engaged. I determined to stop this. To this end I regarded the Army of the Potomac as the centre, and all west to Memphis…the right wing; the Army of the James…as the left wing, and all the troops south, as a force in rear of the enemy…My general plan now was to concenetrate all the force possible against the Confederate armies in the field…Accordingly, I arranged for a simultaneous movement all along the line [in early May].

His keen perception of all federal forces as one concerted grand army finally allowed the North to bring its manpower and materiel superiority to bear. This approach, moreover, threatened all Graycoat armies east of the Mississippi, thus allowing none to reinforce another more endangered. Most significantly as events actually developed, Grant’s grand strategy undercut the Virginia powerbase by devouring the rest of the Confederacy, on which the Old Dominion depended for manpower and supplies.

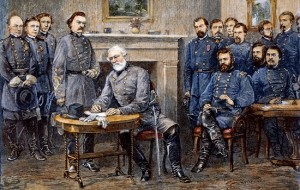

An illustration of Robert E. Lee's surrender to Ulysses Grant based on an 1887 illustration by Alfred R. Waud

Yet Grant also determined to defeat Lee directly. The Illinoisan became an “army group” commander in central Virginia, initially coordinating George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac and Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps and after mid-June Meade’s army and Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James (later Edward Ord’s). Grant left grand tactics and minor tactics to his army and corps commanders. The lieutenant general concentrated on theater and front strategy. whether to strike, when to attack, where to advance, who to command, how to allocate forces among sectors and fronts and theaters, and which reinforcements to obtain - these were the elements of strategic leadership which he exercised.

Right away, his deep understanding of logistics, founded in Mexico and forged in Mississippi, led him to abandon the vulnerable Orange & Alexandria Railroad, along which Pope and Meade had suffered setbacks. He instead advanced by his strategic left flank so as to draw supplies along Virginia’s tidal rivers, from the Potomac to the James, invulnerable supply lines which the Secessionists could never sever.

To use such lines of communications, Grant risked entering the tangled Wilderness of Spotsylvania. He hoped to hurry through there and battle Lee in more open country father south. Grant felt confident of battering the Butternuts badly enough that they could not keep the field but would have to retreat into Richmond, where he hoped to capture them as he had bagged two other armies in Donelson and Vicksburg.

Now as always, however, Lee fought back. The great Virginian struck the Yankees in the Wilderness, where terrain offset manpower and artillery preponderance. Massive attacks and counterattacks, 5-6 May, proved bloody but inconclusive. Clearly, the opening battle did not bring Grant the expected victory. After such a mauling, all his predecessors against Lee withdrew and rested for months. The Illinoisan paused only one day. Then he moved - not rearward but forward more deeply into Virginia. Stymied tactically, he retained the initiative strategically. he never relinquished it (save for three weeks in July) until he finally destroyed the Army of Northern Virginia.

Heavy fighting erupted again at Spotsylvania during 8-19 May; the North Anna, 23-24 May; and throughout Hanover County, 27 May-3 June. On every field, Grant was checked, tactically. From every field Grant advanced, strategically. In one month, he carried the war from central Virginia to Richmond’s outskirts. He thereby nullified Lee’s proven strategy of protecting Richmond from afar and forced upon the Virginian the constricting inperative of his capital’s close and immediate defense.

These bloody battles, from 5 May to 3 June, cost Grant perhaps 53,000 casualties. Ever since, critics called him a “butcher,” heedlessly slaughtering his own men to inflict irreplaceable losses on the South. The final futile assault at Cold Harbor on 3 June supposedly epitomizes Grant’s mindless “war of attrition.” In truth, Cold Harbor no more characterizes Grant than Malvern Hill typifies Lee. Both officers were far superior generals than those two battles would suggest. Grant, after all, had seen the tactical offensive succeed splendidly from Belmont to Missionary Ridge. Understandably, then, when he first came East, he applied the approach which served him so well in the West. But the East was not the West; the Army of Northern Virginia was not the Donelson garrison; and Robert E. Lee was not John B. Floyd, John C. Pemberton, or Braxton Bragg. These terrible truths Grant learned from spring’s sanguinary struggles. One of his greatest strengths, not only against Vicksburg but throughout the Civil War, was his ability to perceive and apply the lessons of experience.

After 18 June, Grant never assaulted frontally a fortified position thought to be strongly defended until the final grand onslaught of 2 April 1865. Throughout the summer and autumn, his orders to Meade and Butler brimmed with explicit prohibitions against frontal attacks. The general-in-chief was far too protective of his soldiers’ lives to risk them in further onslaughts.

Grant’s war of attrition was never waged tactically. Rather was his war of attrition fought and won in the strategic arena. Grant deprived Lee of the strategic initiative; pinned him in place strategically; ate away at his communications and attenuated his army; and relied on Federal armies elsewhere - principally the Shenandoah Valley, Middle Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas - to consume the Confederacy while he fixed Lee in Virginia. “My own opinion,” Grant informed Sherman on 18 December 1864, “is that Lee is averse to going out of Virginia and if the cause of the South is lost, he wants Richmond to be the last place surrendered. If he has such views it may be well to indulge him until we get everything else in our hands.”

Long before the Illinoisan so summarized his grand strategy, he shifted from above Richmond to below the James River. After resting eight days around Cold Harbor, he daringly struck across the peninsula and over the James against Petersburg, rail center for Richmond. His vanguard overran outer fortifications on 15 June, but the defenders retained Petersburg itself and its three most important railroads, repulsing the great attack of 18 June - the futile assault that persuaded Grant to prohibit further such onslaughts. The defeat of his latest effort to extend his left around the Graycoat right, on 22-23 June, moreover, made him pause to rest his weary armies.

With this pause, the mobile warfare of spring stagnated into the siege of summer. Like all of Grant’s Virginia operations, the siege of Petersburg was not tactical but strategic From his great entrenched camp east of the city and on nearby Bermuda Hundred, he launched intermittent offensives into lightly defended and often unfortified country north of the James River and south of Petersburg. Highlights were his Fourth Offensive, 14-25 August, cutting the Weldon Railroad; his Fifth Offensive, 29 September - 13 October, nearly netting Richmond; and his Seventh Offensive, 5-7 February, extending his left flank southwestward to Hatcher’s Run. From July’s Third Offensive to October’s Sixth Offensive, the timing of his two-pronged strikes north and south of the James evolved from sequential to simultaneous blows. The Sixth Offensive’s total failure, 27-28 October, taught Grant a more fundamental lesson. He thereafter relied on massive first strikes with his left wing: the strategy that carried him to Hatcher’s Run in February and to total victory in April.

Throughout these operations against Lee, Grant continued performing his responsibilities as general-in-chief. He diverted some of his own forces to the Shenandoah Valley, first to contain and then to crush that granary’s defenders. He coordinated with his friend Sherman in capturing Atlanta, marching to the sea, and driving northward through the Carolinas to threaten Lee’s rear. He fumed at subordinates’ tardiness in invading Alabama. And he begrudged great victories to his rivals Rosecrans and Thomas, who helped destroy the last invasions of Missouri and Tennessee late in 1864.

By spring 1865, most of Philip Sheridan’s victorious valley veterans had rejoined Grant. Other Federal armies threatened Virginia from the northwest, west, and south. Grant unleashed his final offensive, 29 March. skillful and determined as always, Lee fought back and stopped one Union drive after another. But the Northerners kept coming. Sheridan crushed Lee’s last mobile reserve at Five Forks on 1 April. even more decisively, Meade stormed outer Confederate defenses at Boisseau’s House and severed the last outside railroad into Petersburg 2 April. Overnight on 2-3 April Lee abandoned Petersburg, James River, and Richmond itself, and desperately dashed toward North Carolina.

Grant, whose sound strategy placed many Federal forces including cavalry south of the secessionists, blocked Lee at Jetersville. Too weak to break through, the Butternuts fled westward. Grant ripped their rear at Sayler’s Creek on 6 April. First Sheridan and then Ord headed them off at Appomattox Station and Court House during 8-9 April. With Ord in his front and Meade threatening his rear, Lee was trapped. The great Confederate soldier met with Grant, 9 April 1865, and surrendered the once might Army of Northern Virginia. Relentless in war, Grant proved reconciling in victory and accorded the Graycoats honorable terms of surrender.

Appomattox doomed the Confederacy. Within weeks all other Southern armies surrendered or disbanded. Conscious of the war’s great cost, financial as well as human, Grant promptly returned to Washington to begin downsizing the Union army. His presence in the North almost proved fatal when he was singled out as a target in the assassination plot against President Lincoln. Grant’s assassin, however, lost his nerve, and the Victor of Vicksburg lived for another twenty years.

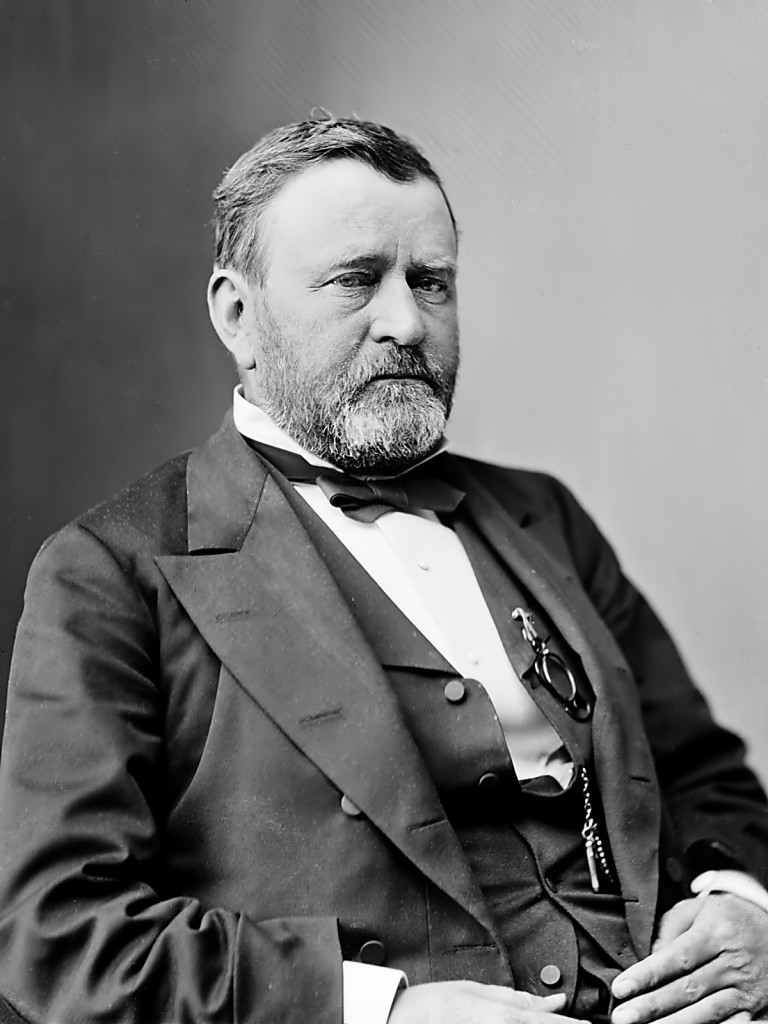

Grant’s great contributions in winning the Civil War earned him promotion to full general on 25 July 1866, the first American officer to achieve four-star rank. Both political parties also sought him as presidential candidate. His increasing alienation from Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction made him more comfortable with Republicans. He was elected eighteenth president of the United States on 3 November 1868. On assuming that office on 4 March 1869, he vacated the generalcy-in-chief.

Grant was reelected on 5 November 1872, and he even considered running in 1880. During his two terms, Colorado joined the Union, and the last four “unreconstructed” ex-Confederate states - Virginia, Georgia, Texas, and Mississippi - reentered Congress. The Fifteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution. On the other turbulent frontier, the West, major victories were won over Indians (despite Little Big Horn), and the policy of putting tribes on reservations began. Internationally, the Alabama Claims, concerning commerce raiding in the Civil War, were arbitrated in America’s favor. Yet his administration was rocked with scandals. His Reconstruction policies, moreover, proved alternately repressive or conciliatory but ultimately ineffective. And the Panic of 1873 caused a major financial downturn throughout his second term. On balance, Grant is not regarded as a great or even successful president.

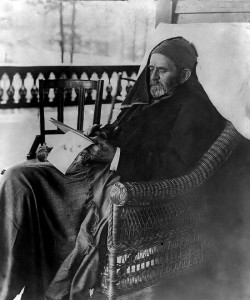

His subsequent career as financier proved disastrous because of dishonesty by those he trusted. His one final success came in writing The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, one of the great autobiographies in American history, made all the more memorable because he wrote it with death imminent. Ulysses S. Grant died of cancer at Mount McGregor, New York, 23 July 1885. He is buried in Grant’s Tomb in New York City. the magnificence of the mausoleum and the memorability of the memoir continue to attract attention - not, however, because of Grant the president but because of Grant the general.

U.S. Grant was the quintessential U.S. general of the nineteenth century. Neither soldier-king nor military genius, he was fundamentally a citizen of the republic, who, will millions of other Americans offered to serve his country in time of crisis. In 1861, he emerged from the obscurity of a small mining town. During the next four years, he led Federal forces to victory. Had he, like Lincoln, been assassinated on 14 April 1865, history would forever honor the greatness and lament the loss of further accomplishments of those two citizens from Illinois.

What elevated Grant above the millions of other soldiers and enabled him to achieve so much was only partially his military background. Unquestionably, his Mexican War experience on the battlefield and as supply officer benefited him in the Civil War. His West Point education cannot have hurt, but that undergraduate institution marked the extent of his schooling. In the mid-nineteenth century, the American military profession was still maturing and had yet to develop the advanced officer education system which highlighted the armed forces from the 1880’s onward. Nor did Grand observe foreign wars, visit foreign armies, or even devote personal study to the profession of arms the way many brother officers who also became Civil War generals did.

Rather did Grant the professional soldier succeed in the sixties because of the innate qualities of Grant the man. In wartime (far more than in peacetime) he understood himself and was comfortable with himself and with exercising command. Because he knew that he was not a luminary of the Old Army, he realized that he had to apply himself all the more diligently during the Civil War in order to succeed. Far from relying on reputation or professional education - let alone, genius - Grant benefited from his especial aptitude for learning from wartime experience, particularly his own. He could perceive and apply approaches that worked and could modify or discard approaches that did not.

Searching for effective approaches, then applying or adapting them, made him responsive to new realities. His flexibility of process, moreover, excellently complemented his fixity of purpose. his unshakable resolve to press on to victory was legendary - highlighted in his campaign against Vicksburg, epitomized in his summation at Spotsylvania: “I…propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” This resolve, like so much of Grant’s generalship, operated in the strategic realm, not the tactical. The mindless massacre of Burnside’s brigades at Marye’s Heights was diametrically opposite to Grant’s approach to warfare.

In pursuing whatever approach would produce the ultimate victory which he felt sure lay ahead, Grant did not dwell on setbacks, linger over battles at hand, or dread possible dangers. The man who never turned back never looked back but always faced forward in search of future opportunity to win battles, campaigns, the war itself. Indeed, so confident was he of eventual victory that even positional disasters (for example, Monocacy) which many Unionists regarded as calamities Grant perceived as opportunities to attack the attacking Southerners.

Such certainty of success strengthened Grant in adversity or inspirited him to victory. Hooker’s hollow boasting or Sheridan’s appalling arrogance had no counterpart in Grant’s character. Rather was his certainty grounded in calm, quiet, self-assured confidence that he could do the job. “Our work progresses here slowly, and I feel will progress securely until Richmond finally falls,” he wrote to Julia as the Petersburg siege began; “the task is a big one and has to be performed by some one.” Month after month, the siege continued. That Christmas eve, he wrote her, “I know how much there is dependent on me and will prove myself equal to the task. I believe determination can do a great deal to sustain one, and I have that quality certainly to its fullest extend!”

Grant’s self-assurance, willingness to look forward, and moral courage in combining flexibility of method with fixity of purpose understandably manifested themselves in onward movement. Grand strategically, strategically, grand tactically, and tactically, he carried the conflict to the Confederates. Maintaining the initiative offensively enabled him to control the course of operations dominate the strategic and tactical domains, and compel the Secessionists to react to him. This approach he summarized in recounting his first (overland) drive against Vicksburg: “My entire command was no more than was necessary to hold these [extended supply] lines, and hardly that if kept on the defensive. By moving against the enemy and into his unsubdued, or not yet captured, territory, driving their army before us, these lines would nearly hold themselves; thus affording a large [Federal] force for field operations.”

Grant’s self-assurance, willingness to look forward, and moral courage in combining flexibility of method with fixity of purpose understandably manifested themselves in onward movement. Grand strategically, strategically, grand tactically, and tactically, he carried the conflict to the Confederates. Maintaining the initiative offensively enabled him to control the course of operations dominate the strategic and tactical domains, and compel the Secessionists to react to him. This approach he summarized in recounting his first (overland) drive against Vicksburg: “My entire command was no more than was necessary to hold these [extended supply] lines, and hardly that if kept on the defensive. By moving against the enemy and into his unsubdued, or not yet captured, territory, driving their army before us, these lines would nearly hold themselves; thus affording a large [Federal] force for field operations.”

His broadening responsibilities, moreover, enabled him to bring increased force to bear against the Confederacy. His grasp of grand strategy caused him to concert the armed might of the Union. His understanding of logistics led him to keep his forces well supplied. Throughout the Civil War, the North enjoyed vast preponderance of manpower and materiel. One of Grant’s greatest strengths, which elevated him above other Yankee generals, was his ability to convert these potential advantages into positive achievements.

He was, furthermore, permitted to apply his strengths, approaches, and self-confidence because he understood that his national enemy was centered in Richmond, not Washington. Like Lee and unlike McClellan Rosecrans, P.G.T. Beauregard, Joseph E. Johnston, and other talented generals on both sides, Grant recognized that in a wartime republic, the president is never a meddler. The president has the right to involve himself in national strategy and the conduct of war. Great generals like Grant and Lee worked with their respective presidents instead of fighting them. Grant earned Lincoln’s trust while first serving in the West; he kept that confidence after coming east. By making clear he welcomed the president’s involvement, Grant was actually accorded greater latitude to apply his abilities than were generals whose resistance provoked their presidents to rein them in. Indeed, the effective working relationship between Lincoln and Grant (and the comparable relationship between Jefferson Davis and Lee) exemplifies how a constitutional commander-in-chief and a uniformed general-in-chief should work together in wartime.

Grant’s command relations with his brother officers were more mixed. Here his great sense of loyalty and his fixity of determination sometimes served him and the Union well but not always. In some cases, he recognized able officers and advanced them to increasingly more responsible positions, such as Sherman, Sheridan, Ord, Steele, James B. McPherson, James H. Wilson, George Crook, and Chief of Staff John A. Rawlins. He also shunted aside more marginal generals McClernand, Stephen A. Hurlbut, and Charles S. Hamilton. Less laudably, howver, Grant sidetracked some sound soldiers who crossed him or apparently rivaled him: Rosecrans, Thomas and Gordon Granger. Only Lew Wallace managed to fall from Grant’s grace and then restore himself during the war. Then, too, Grant continued according undeserved admiration to such officers as David Hunter and Franklin long after their wartime record made clear they were not living up to prewar reputations. Even for generals whom he respected, such as Meade, he sometimes showed unintentional insensitivity that bruised that highly competent but high-strung commander. This decidedly mixed record with subordinates and staff presaged the poor personnel selections scarring his presidency.

Nor was Grant a great leader of men. Qualities which bonded other commanders to their soldiers - Lee’s awe-inspiring nobility, McClellan’s captivating magnetism, Sheridan’s rousing electricity - were lacking int eh general from Galena. Grant never inspired his soldiers to love him, and only one great occasions did they cheer him, certainly not every time he passed marching columns. But neither did they hate him as they hated Buell, Charles Gilbert, or Irvin McDowell. and in his own quiet way he loved them: not in the hot, effusive shouting love of parades and rallying cries but in a calm, dedicated determination to provide for them, to care for them, to uphold their rights when captured even after military necessity made him cancel prisoner exchanges, to use them in battle when necessary but never to squander their lives needlessly. “Grant the Butcher” was far too devoted to his soldiers ever to risk their lives without good cause.

Yet his war of attrition unquestionably took its toll. Although he waged that war strategically against the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederacy, the severe fighting, 5 May - 18 June 1864 inflicted heavy losses on both sides tactically. Such casualties were not just quantitative but qualitative, often claiming the best officers and the bravest soldiers. Some returned to duty; all too many were killed, captured, or wounded out. Those losses dulled the fighting edge of his forces and impeded his ability to shorten the war.

His willingness to incur such casualties in order to help produce victory was both a weakness and a strength in his generalship. His aforementioned mixed record in dealing with fellow officers also dimmed the luster of his leadership. Grant would readily acknowledge that he was not a perfect general any more than that he was a perfect person. Yet, on balance, his many strengths as a commander, which derived largely from his many strengths of character, accomplished great results that were central to Federal victory. These achievements mark Ulysses S. Grant as the greatest general of the Northern army and one of the greatest generals of American military history.

-Richard J. Sommers

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 863-872]

For further reading:

Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. 1885.

Flood, Charles Bracelen. Grant’s Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant’s Heroic Last Year. Da Capo Press. 2011.

Kaltman, Al. Cigars, Whiskey and Winning. Leadership Lessons from Ulysses S. Grant. Prentice Hall Press. 2000.

Smith, Jean Edward. Grant. Simon & Schuster. 2002.

Pingback: Bombardment of Fort Henry (Feb. 2-6, 1862) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, C.S.A. (Jan. 18,1816- May 16,1863) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: This Week in the American Civil War - Feb. 12-18, 1862 | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: March 6-8, 1862-Battle of Pea Ridge | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: Battle of Fort Donelson (Feb. 13-16, 1862) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Battle of Fort Donelson (Feb. 13-16, 1862) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: This Week in the Civil War - April 2-8, 1862 (150 years ago) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history – Lee Surrenders at Appomattox Court House – April 9, 1865 | This Week in the Civil War