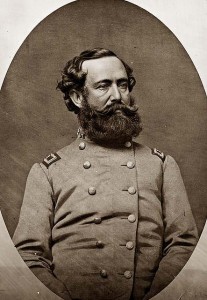

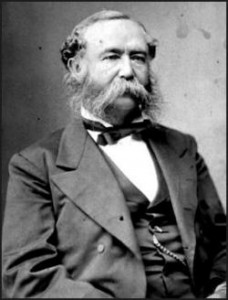

Born Wade Hampton III in Charleston, South Carolina, the man who would assume J.E.B. Stuart’s mantle had much to live up to even at birth. His grandfather, the first Wade Hampton, had served in the American Revolution, and both his father and grandfather had fought in the War of 1812. Along the way, the Hampton family had amassed an enormous fortune from cotton plantations in South Carolina and Mississippi and a profitable sugar plantation in Louisiana. This fortune would propel the scion of the family to a series of terms in both houses of the South Carolina legislature between 1852 and 1860.

A large slaveholder, Hampton yet evinced Unionist political sympathies throughout his political career. However, when his native Palmetto State seceded, Hampton quickly threw in his lot with the Confederacy, using his own personal fortune to raise and equip a force of infantry, cavalry, and artillery known as Hampton’s Legion. A number of South Carolina’s important, and colorful, brigadiers, including Martin W. Gary and Matthew C. Butler, would cut their teeth in Hampton’s Legion during the early days of the war.

Shortly after receiving a colonelcy, Hampton first saw combat at the battle of First Bull Run. On 19 July, he moved his troops from the environs of Richmond to Manassas Junction, detraining in the midst of the fight. Late in the day on 21 July, Hampton suffered the first of his many war wounds, a minie ball cutting down the colonel as he led his infantry against Henry House Hill. Hampton would receive another slight wound the following June at Seven Pines.

In May 1862, Hampton was promoted to brigadier general and granted command of one of Jeb Stuart’s two cavalry brigades, the other being commanded by Fitzhugh Lee. This undoubtedly suited the six-foot tall South Carolinian, who had spent much of his youth atop a horse, avidly engaged in all manner of field sports. One observer of the general’s equestrian acumen noted that Hampton upon a horse looked like nothing so much as a centaur.

In June of 1863, Hampton’s performance at Brandy Station provided a glimmer of his possibilities as a cavalry commander. This engagement also foreshadowed the personal tragedy that would stalk him throughout the war, one of his brother’s fell in a confused exchange of fire just five miles south of the main engagement. Later that month, Hampton played an important role in Stuart’s efforts to contain the increasingly professional Federal cavalry while the Confederate army moved down the Shenandoah Valley into Pennsylvania. The South Carolinian led a charge at Ashby’s Gap that confirmed to many observers his personal battlefield charisma.

The battle of Gettysburg saw the genesis of a controversy with Fitzhugh Lee that would dog Hampton during the remainder of his tenure with the Army of Northern Virginia. The young Lee had ordered a calamitous charge in Hampton’s presence and Hampton suffered perhaps his worst wounding of the war, at least two saber strokes to the head and a shrapnel wound in the leg, while attempting to retrieve and rally his cavalry. During Hampton’s convalescence, both he and Fitz Lee received promotion to major general, a move intended to salve hard feelings between the two cavalrymen and to transform the Confederate army’s cavalry arm into a clearly defined command corps.

After the death of Stuart at Yellow Tavern in 1864, Robert E. Lee again attempted to navigate choppy waters by appointing neither his nephew nor Hampton to command the cavalry, instead ordering both to report directly to him. This state of affairs continued until the cavalry engagement at Trevilian Station in June. Hampton’s hard fighting and dexterous use of the topography in his role in checking Philip Sheridan’s charge on Richmond seems to have convinced Lee to grant Hampton command of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Corps in September 1864.

The defense of Petersburg showed Hampton at his best, carrying out a series of sorties, raids, and flank actions that did much to sustain the Confederacy’s tenuous morale. The most audacious of these actions came to be known as the Hampton Beef Raid. In a spectacular move worthy of the indefatigable Stuart, Hampton led three brigades in a raid around the Federal left, rustling 2,500 beeves grazing six miles to the rear of Ulysses S. Grant’s City Point headquarters. In late October, Hampton brilliantly checked a probing attack on the Confederate army’s south flank in the battle of Burgess Mill. The cost of this success, however, proved prohibitively high for Hampton personally, as one of his sons, Frank Preston Hampton, fell to a volley of Federal fire that also gravely wounded another son, Wade Hampton, Jr.

Hampton was transferred to Joseph Johnston’s command in January 1865. Lee and Johnston hoped that the Carolinian could stir his native state to resist Sherman’s advance, to that end promoting Hampton to lieutenant general in February. Little came of these hopes, and Hampton spent much of the remaining months of the war helping to orchestrate a series of often unsuccessful retreats. Hampton was not interested in surrendering with the army he had served in since the early days of the war. After both Lee’s and Johnston’s surrender, the one-time Unionist exchanged correspondence in April with a fugitive Jefferson Davis, correspondence in which he urged Davis to continue the fight in the Trans-Mississippi. Missing Davis’s small band at Charlotte as the president of the fallen Confederacy moved South to eventual capture, Hampton seems to have realized that the cause had truly become lost.

The end of the war found the once wealthy Hampton destitute, a number of his plantations destroyed, and the family home of Millwood near Columbia burned by Sherman’s troops. Though never able to recoup his financial losses, Hampton played a central role in redeeming South Carolina from its Reconstruction government and became governor in 1876. Hampton later served as a U.S. Senator, earning a reputation throughout his political career for both honest fiscal policies and racial moderation and being one of the few Bourbon Democrats to appeal for the votes of emancipated blacks. Hampton died at his Columbia home in 1902.

- W. Scott Poole

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 920-922]

Hampton is buried in Trinity Episcopal Cathedral Cemetery in Columbia, South Carolina.

Further reading:

- Cisco, Walter Brian. Wade Hampton: Confederate Warrior, Conservative Statesman. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2004.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee’s Lieutenant’s: A Study in Command

- Longacre, Edward G. Gentleman and Soldier: A Biography of Wade Hampton III. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- Meynard, Virginia G. The Venturers, The Hampton, Harrison and Earle Families of Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas, Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, Inc., 1981.

- Swank, Walbrook Davis. Battle of Trevilian Station: The Civil War’s Greatest and Bloodiest All Cavalry Battle, with Eyewitness Memoirs. Shippensburg, PA: W. D. Swank, 1994.

- Wellman, Manly Wade. Giant in Gray: A Biography of Wade Hampton of South Carolina. Dayton, OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1988.

- Willimon, William H. Lord of the Congaree, Wade Hampton of South Carolina. Columbia, SC: Sandlapper Press, 1972.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Final Campaign. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2006.