By Darryl Sannes

Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force

The Second Minnesota Volunteer Infantry distinguished itself during actions at the Battle of Mill Springs, Ky., 150 years ago Thursday. The regiment faced Confederate soldiers from Mississippi and Tennessee during the battle, and captured the colors of a Confederate regiment.

The Second Minnesota Volunteer Infantry distinguished itself during actions at the Battle of Mill Springs, Ky., 150 years ago Thursday. The regiment faced Confederate soldiers from Mississippi and Tennessee during the battle, and captured the colors of a Confederate regiment.

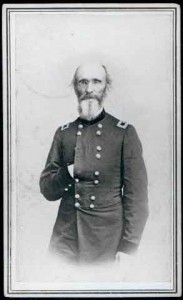

The Second Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment was organized in the summer of 1861 with Col. Horatio Phillips Van Cleve selected to command the regiment by Governor Alexander Ramsey.

On September 22, 1861, all of the detached companies of the regiment were recalled from post and garrison duty at the frontier forts in Minnesota and ordered to report to Fort Snelling. On October 14 the regiment boarded steamships with the intention of being sent to Washington, D.C. to join the Army of the Potomac, but their orders were changed en route and the regiment was sent instead to Louisville, Kentucky to join the Army of Ohio under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas.

On January 17, 1862, when the Union forces marched to within nine miles of the Confederate entrenchments, at Mill Springs, Ky., Confederate Maj. Gen. George Bibb Crittenden ordered his division commander, Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, to leave the camp and attack Thomas’s Division before they could mass and assault them. During the night of Jan. 18, Confederate forces left their camp and marched for a surprise attack in the morning.

At first light on the morning of Jan. 19, the Second Minnesota soldiers awoke to the sound of gunfire. It was the first hostile gunfire they ever heard. The soldiers quickly sprang into the lines and marched quickly to the battlefield where they were placed to the left of the Ninth Ohio Infantry and were personally ordered into the fight by General Thomas.

Through the dimly lit woods and the morning haze, the Second Minnesota advanced along the Mill Springs Road until coming upon a rail fence and an open field. At a distance of approximately 150 yards, the regiment immediately exchanged fire with a line of nearby Confederates, which quickly disappeared. This happened to be the Confederate regiment’s second line, while the Confederate’s first line suddenly appeared in the rear of the Minnesota regiment.

The Confederate’s Twentieth Tennessee Infantry Regiment arrived at the fence about the same time and the opposing forces had surprised each other. In his official report, brigade commander Col. Robert McCook wrote, “Along the lines of each of the regiments, and from the enemy’s front a hot and deadly fire opened. On the right wing of the 2nd Minnesota regiment the contest was at first almost hand-to-hand; the enemy and the 2nd Minnesota were poking their guns through the same fence. However, before the fight continued long in this way, that part of the enemy contending with the 2nd Minnesota regiment, retired in good order to some rail piles hastily thrown together.” The fighting lasted a half hour.

The left of the Confederate line was flanked by the Ninth Ohio and the right by the Second Minnesota, which caused the entire Confederate line to break and retreat to their entrenchments along the Cumberland River. The Second Minnesota, with the rest of the Union Army, pursued the retreating Confederates to the brink of the entrenchments, until darkness interrupted the advance.

Captain Judson Bishop of Company A recalled his experiences during the Mill Springs battle. “The condition of things could not and did not last long after our boys really discovered and got after them; many of the enemy were killed and wounded there, but more after they got up and were trying to get away,” he wrote in the regiment’s history, Service of the Second Regiment Minnesota Veteran Volunteer Infantry In the Civil War of 1861 to 1865.

“One lieutenant, as the firing ceased and the smoke lifted, stood a few feet in front of Company ‘I’ of the 2nd and calmly faced his fate. His men had disappeared and he was called on to surrender. He made no reply but raising his revolver fired into our ranks with deliberate aim, shooting Lieut. Stout through the body. Further parley was useless and he was shot dead where he stood. He was young Bailie Peyton, the son of a noble sire, whose sword, presented by the citizens of New Orleans for his gallant service in the Mexican war, was here found on the dead body of his son. We met his father later at his home near Gallatin, Tennessee. He was one of the foremost Union men of his state and it was an inexpressible grief to him that his only son should have enlisted in the Rebel cause. He said that his only comfort was, in the reflection that he did not die as a coward,” Bishop added.

Lieutenant Stout’s body was placed onto a stretcher and removed from the battlefield. One of the stretcher bearers was none other than Minnesota State Treasurer Charles Scheffer, who visited the regiment in order to receive the soldier’s allotments that were to be paid to their families back home.

The body of Peyton was passed through the lines to the Confederates along with that of Brig. Gen. Zollicoffer, who was shot in the heart by 4th Kentucky Infantry Col. Speed Smith Fry, after the Confederate general accidentally wandered into Federal lines.

“The body had been dragged out of the way of passing artillery and wagons, and lay by the fence, the face up-turned to the sky and bespattered with mud from the feet of marching men and horses. It was decently cared for later, and, with that of Lieut. Bailie Peyton, was sent through the lines to Nashville for internment… The battle was over, and the mob of demoralized fugitives in the distance were rapidly getting out of sight,” Bishop recalled.

The next morning the Federal forces marched into the abandoned Confederate camp, since the Confederates had escaped across the Cumberland River during the night. Of the 600 Minnesotans engaged in the battle, 12 were killed with 33 wounded. Total Federal losses were 39 killed and 207 wounded.

The Confederates lost 600 total, but their biggest loss was General Zollicoffer.

In their hurried retreat the Confederates had left virtually everything in their camp. Union forces took possession of 12 artillery pieces with their caissons packed with ammunition, a large amount of small arms and ammunition, 150 to 160 wagons and more than 1,000 horses and mules. Federal troops also took possession of six Confederate battle flags including one captured by the Second Minnesota.

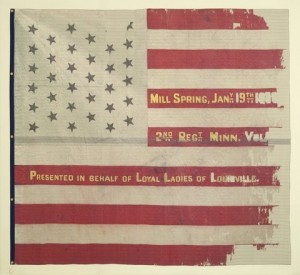

Battle Flag of the 2nd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry - part of the Civil War Battle Flags conservation project, Minnesota Historical Society

The Battle of Mills Springs was the first Union victory of the war and gave a glimmer of hope to the American people and Union forces that had only experienced defeat to this point. At the close of the Mill Springs Campaign in February, 1862, the Second Minnesota returned toLouisville. While there they were presented with a beautiful silk banner, presented by the Loyal Ladies of Louisville, after the regiment had helped win the Battle of Mill Springs and had become known as the “Saviors of Kentucky.”

The Second Minnesota would go on to distinguish itself in many more battles throughout the Civil War. Col. Van Cleve was promoted to brigadier general on March 21, 1862 for his regiment’s actions at Mill Springs and was promoted to major general following the war. Bishop later led the regiment as it’s colonel before the war’s conclusion. Mill Springs was the first combat action for both men.

[amazon_enhanced asin=”0878391266″ /]

List of 2nd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry soldiers

killed and wounded at Mill Springs

Private H. C. Reynolds, Company B – Killed

Private Milo Crumb, Company B – Killed

Private William H. H. Morrow, Company D – Killed

Private Fred Bohmbach, Company G – Killed

Private John B. Cooper, Company B – Killed

Private Andrew Dresco, Company B – Killed

Private H. R. Thompson, Company E – Killed

Private Gustave Rommel, Company G – Killed

Private Fred Stomshorn, Company G – Killed

Private Jacob Warner, Company G – Killed

Private Samuel H. Parker, Company I – Killed

Private Frank Schneider, Company I – Killed

Captain William Markham, Company B – Wounded

2nd Lieutenant Tenbroek Stout, Company I – Wounded

Corporal Ed Cooper, Company B – Wounded

Private W.C. Smith, Company B – Wounded

Private Ira G. Walden, Company B – Wounded

Private John Etzel, Company B – Wounded

Private Cornelius White, Company B – Wounded

Private J. B. Chamber, Company B – Wounded

Private John Mabold, Company E – Wounded

Private J. R. Brown, Company E – Wounded

Private O. P. Renne, Company E – Wounded

Sergeant Anton Morgenstern, Company G – Wounded

Private Frank Kiefer, Company G – Wounded

Private Charles Schultz, Company G – Wounded

Private Charles Vanke, Company G – Wounded

Private Henry H. Hammen, Company G – Wounded

Private William Kemper, Company G – Wounded

Private George Dehnning, Company G – Wounded

Private Henry Clinton, Company I – Wounded

1st Sergeant Thomas McDonough, Company K – Wounded

Corporal F. V. Hotchkiss, Company K – Wounded

Corporal Alexander Grant, Company K – Wounded

Corporal J. B. Pomeroy, Company K – Wounded

Private John Benson, Company K – Wounded

Private Henry F. Cook, Company K – Wounded

Private Alexander Partman, Company K – Wounded

Private W. K. Haskins, Company K – Wounded

Private John Smith, Company K – Wounded

Private P. S. Barnett, Company K – Wounded

Private Thomas Johnson, Company K – Wounded

Private G. Plowman, Company K – Wounded

Private C. F. Westland, Company K - Wounded

For information on the Civil War Trust’s effort to save 16 acres of the Mill Springs battlefield, click here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * **

THE BATTLE OF MILL SPRING, KY.; PART TAKEN BY THE MINNESOTA SECOND.

Published in the New York Times February 16, 1862.

The following extract from a private letter written by a member of the Minnesota Second Regiment, gives some interesting particulars of the battle of Mill Spring:

The Eighteenth Regulars have, in one or more accounts, received the credit of the fight; in others it is stated that they made a forced march of twenty-five miles to be at the fight, but arrived too late. They made only the usual day’s march which they would have made if there had been no battle, and did not get within twelve miles of the battle-field for two days after it occurred.

WOOLFORD’s Cavalry have also received great glorification. They were the first to meet the enemy, and they were the first and best runners of the day. They are mounted rifles, in fact, and ought to have fought step by step, the whole ground, but they did not fight well.

The next in was the Tenth Indiana, two of whose companies were on picket, and the Lieutenant-Colonel sent another to their support, and then detached another company still, after the enemy had engaged his regiment, to check a regiment of rebel horse that was turning his right flank. He found his men scattered, of course, for he had scattered them, and they soon broke and took to fighting on their own hook.

The fourth Kentucky then came into action, and if the Tenth had been together, they could have kept their form, but as it was (with the dispositions of their officers) they could not help going in on their own individual nerve, men and all, and they became a mere rabble, which the enemy had, with a little loss, already reached, and were about to slaughter as they ran, when the Ninth Ohio and our Second Minnesota came into play. Right up to the ground occupied by these two regiments we came, having met man after man of WOOLFORD’s Cavalry and of the Tenth Indiana running with good will and breath, who cried out, “For God’s sake, hurry up!” “We are all cut up!” “Go in, boys, you’ll get all you want!” “We are all whipped again!” (“You’re a d — d liar!” replied one of the Second Minnesota,) and such things.

Just as they reached the mob of the Tenth and Fourth aforesaid, they got a volley from the enemy, and the Tenth and Fourth fell through their ranks, and our boys pitched in. Both forces were about equally near to a fence, (rail, Virginia, you know,) but the rebels did not, except the more hardy, get nearer to it than they were at first — about twelve yards — except in one place, where the ascent to it had been easier; and there they lay right behind it, at the first volley from us. File-firing instantly became the order of the day. The men picked out the nearest cover — log, tree, fence-rail, or whatever — and would load kneeling; then step out to a clear view to fire, every time getting nearer and nearer to the fence, and with every round, getting less and less careful of going under cover to load. They did not, one-fourth of them, ever fire a shot without having just seen a “secesh” in the place aimed at. They were as cool as boys shooting at squirrels. They quarreled with each other for particularly eligible spots for aiming, and the enemy heard them telling each other the casualties as they occurred, and exhorting each other to “give ’em hell for JIM’s sake.”

The blaze of the guns mingled, and in some places the gun-barrels actually rested across, the same fence-rail which fired at the hostile forces, at one and the same instant. For a half hour the Second Minnesota fought thus, while the Ninth Ohio, which was on their right in the woods, met an enemy also in the woods. They were not so near as the Second, and both parties took to trees when firing. But in a little while the Ninth fixed bayonets, and charged on the rebels. The enemy were not so numerous who opposed them, and the Dutchmen are rough-looking fellows on a charge.

The “secesh,” at the same moment, in front of the fire of the Second and the bayonets of the Ninth, remembered some unfinished business, which would not admit of delayed attention, over in the vicinity of their camp about nine miles, and laying down their guns and equipments, they hurried off to attend to those duties.

The Twelfth Regiment had been sent to flank their right, but having woods and every sort of obstacle in their way they did not arrive in time to be of any service, except to pick up a dozen or two prisoners. The Second Minnesota was in the closest and hottest of the fight, and though engaged for only a short half-hour, and in a peculiarly sheltered position — having one company absent on picket duty — only six hundred and twenty-one men engaged — and three companies so sheltered that not a man was touched — it lost most men killed, and second wounded, (I believe first in both.) Twelve fell and expired on the field, thirty-three were wounded.

Five regiments were engaged, and I claim that the Second Minnesota and Ninth Ohio won the fight, and I admit that one would have been roughly handled without the other; but no three rebel regiments can whip the two. The next in deserving was the Fourth Kentucky and the men of the Tenth Indiana. I cannot say the officers were of any use to them. The men had a hard position, and did as well as they could while distracted by such diverse and bewildering orders of mad, hair-brained officers. Several other regiments would have had a chance in if the enemy had not left in such haste.

The Second Minnesota had the enemy nearer than any other regiment, a rest for their aim almost always, and the rebels in an open field, although behind logs and stumps. The most of the dead and wounded were in front of their lines, and I claim that it inflicted the most damage on the enemy. It was the Mississippi Tigers, with their 16-inch knives, that lay behind every log and stump in front of us.

So much for the truth of history. ARGUS.

Pingback: On this Date in Civil War History: January 19, 1862 - Battle of Mill Springs (150th Anniversary) | This Week in the Civil War