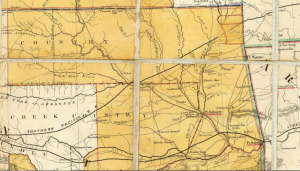

Inhabiting the area between the Arkansas and Canadian rivers in eastern Indian Territory, the people of the Creek Nation viewed the onset of the American Civil War with mixed emotions. Factions existed within the Creek Nation, but these divisions has endured since the mid-eighteenth century when English and Scottish fur traders established ties with the Lower Creeks in Georgia and Alabama. Intermarriage led to an increase of mixed-bloods among the Lower Creeks and the appearance of Creek leaders with the names such as McGillivray and McIntosh. The Lower Creeks voluntarily complied with the United States’ removal policy of the 1830s endorsed by their mixed-blood leaders, while the Upper Creeks had to be forcibly removed from their traditional homelands. These two Creek factions remained separated in Indian Territory, but they were able to put their animosity aside long enough to establish a seat of government, devise a phonetic written language, draft a slave code, and build schools (with the aid of missionaries) in the 1840s and 1850s.

On 10 July 1861, Principal Chief Motey Kinnard and Daniel N. and Chilly McIntosh (sons of William McIntosh – former principal chief of the Lower Creeks) met with Special Commissioner Albert Pike of the Confederate Bureau of Indian Affairs and together signed a treaty of alliance with the Confederacy. The McIntoshes also promised to raise a regiment of Creeks, provided they would only have to fight within the borders of Indian Territory. However, in the fall of 1861 thousands of loyal and neutral Upper Creeks refused to recognize the treaty of alliance with the Confederacy signed by the Lower Creeks, and prepared to march with their leader, Opothleyahola, to Kansas and safety. A force of Lower Creeks under the McIntosh brothers opposed them. In November, sporadic violence between the two factions began and quickly intensified. Pike ordered Colonel Douglas H. Cooper to take charge of the situation and restore tranquility among the Creeks while the special commissioner departed for the Confederate capital. Cooper called on other Indian home guard units to aid in his efforts to end the hostilities and prevent the Upper Creeks from leaving Indian Territory. In doing so, Cooper began what amounted to a civil war within the borders of the territory.

When Cooper arrived near the Canadian River, he discovered almost 4,000 Upper Creek men, women and children as well as Indians from assorted other nations crowded into encampments along with their livestock, wagons, and worldly possessions. About one-third of these Indians were armed. After failing to dissuade the Upper Creeks from their mission, Cooper chose to use force. Considering these Indians to be a threat to Confederate authority in Indian territory, Cooper assembled a body of 1,400 mounted soldiers composed of six companies of his Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment, Daniel McIntosh’s Lower Creek regiment, Chilly McIntosh and John Jumper’s battalion of Creeks and Seminoles, and 500 whites of the 9th Texas Cavalry. On 5 November 1861, the ever-growing group of loyal Creeks and refugees left their encampments and moved north toward Kansas. Two weeks later, Cooper attacked the slow-moving caravan at Round Mountain, near the junction of the Cimarron and Arkansas rivers. The loyal Creeks fought back, managing to escape at dusk after setting a prairie fire to impede Cooper’s progress.

Slowed but undaunted, Cooper resumed the chase, now reinforced by John Drew’s Cherokee regiment, which was ordered by Cooper to aid in the operation. On 9 December, Cooper found Opothleyahola and the loyal Creeks waiting for him at Chusto-Talasah, or Caving Banks, on Bird Creek near present-day Tulsa. Cooper engaged the Upper Creeks for four hours before Opothleyahola finally withdrew his band. All told, Cooper lost fifteen men killed and thirty-seven wounded, and failed once again to cut off the fleeing loyalists.

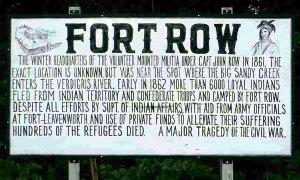

Although claiming a victory, Cooper nevertheless withdrew to Fort Gibson near Tahlequah and waited for reinforcements from Texas and Arkansas. With the arrival of 1,380 Confederate troopers under Colonel James McIntosh, Cooper had the luxury to plan a combined attack against Opothleyahola’s band utilizing the converging columns of his own and McIntosh’s troops. The Confederates once again took to the field, but unfortunately were unable to synchronize their convergence on the Creek camp at Chustenahlah. Rather than wait for Cooper’s badly delayed troops, McIntosh chose to engage Opothleyahola’s numerically superior forces on 26 December. Weakened by exhaustion, cold weather, and lack of adequate food, the loyal Creeks could not withstand the Confederate onslaught. Warriors mixed with men, women, and children fled the field in panic pursued by white Confederate cavalrymen and the recently arrived mixed-blood Cherokee regiment under Stand Watie. Watie’s 300 men killed or captured many of the stragglers who were too weak to flee. Those who did escape finally made their way to Kansas and safety. There they fared little better, owing to a lack of adequate food, clothing, and shelter for the winter. U.S. Indian agents in Kansas were unable to aid the refugees, whose numbers eventually swelled to over 10,000. Eventually hunger and disease took their toll.

In the spring of 1862, Brigadier General James G. Blunt, commander of the Union Department of Kansas, decided to return the loyal Indian refugees to their home in Indian Territory. The resulting operation resulted in frequent skirmishes with Confederate forces as the refugee column and its Federal escort entered Cherokee country north of the Arkansas River. The return of this contingent of loyal Creeks to Indian Territory fanned the flames of factionalism within the Creek Nation. While Creek soldiers participated in conventional military operations such as those that led to the Battle of Honey Springs on 17 July 1863, the real fateful combat for the two factions of the Creek Nation came in the form of guerrilla raids upon each other that sowed the seeds for continued strife well after the war’s end.

- Alan C. Downs in the Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History by David S. and Jeanne Heidler. pp. 518-519]

Additional Reading:

Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: December 9, 1861 - The Battle of Chusto-Talasah (150th Anniversary) | thisweekinthecivilwar

Great history, thank you very much!

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: November 19, 1861 - Battle of Round Mountain (150th Anniversary) | thisweekinthecivilwar

Pingback: On this date in the Civil War: December 26, 1861 - The Battle of Chustenahlah (150th Anniversary) | thisweekinthecivilwar

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: December 9, 1861 - The Battle of Chusto-Talasah (150th Anniversary) | thisweekinthecivilwar