Ball’s Bluff was a small battle by the standards of the Civil War, but it had ramifications far beyond its size. It was only the second significant battle in the east, and received a great deal of attention in both North and South. Edward Baker, a senator from Oregon and close personal friend and political ally of President Lincoln, was killed during the battle and became a martyr to those who took a hard line against the Confederacy. Perhaps most importantly, the defeat spurred the creation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War by Congress; the Committee became a persecutor of those who were considered to be soft on defeating the Confederacy and destroying slavery.

Ball’s Bluff was a small battle by the standards of the Civil War, but it had ramifications far beyond its size. It was only the second significant battle in the east, and received a great deal of attention in both North and South. Edward Baker, a senator from Oregon and close personal friend and political ally of President Lincoln, was killed during the battle and became a martyr to those who took a hard line against the Confederacy. Perhaps most importantly, the defeat spurred the creation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War by Congress; the Committee became a persecutor of those who were considered to be soft on defeating the Confederacy and destroying slavery.

George McClellan took command of Union forces around Washington, D.C., in the wake of the defeat at Bull Run in July 1861. He immediately set about training and improving the state of his army. As the good campaigning weather of fall 1861 passed, however, he began to feel pressure to advance on the Rebel forces just across the Potomac River from Washington. Probes and raids by Yankee forces over the Potomac combined intelligence gathering with training. On 19 October McClellan ordered General George McCall to conduct a reconnaissance toward the village of Dranesville, Virginia, covering a topographical survey of the area. McClellan alerted neighboring commander General Charles P. Stone of the movement and told him to keep a vigilant watch on the town of Leesburg; if the Rebels evacuated it, he could move in. A “light demonstration’ on Stone’s part would help move them on.

Stone moved one brigade to the Potomac opposite Leesburg. When an inexperienced scouting party crossed into Virginia during the night of 20 October, it mistook shadows for an unguarded Confederate camp. Stone ordered Colonel Charles Devens and 300 men to make a dawn attack. If no other Confederate forces were found, Devens was to stay on the Virginia side and conduct a further reconnaissance. When Devens found no camp, he pushed on to Leesburg, which he found empty of enemy troops. Devens requested reinforcements so that he could hold Leesburg.

When Stone ordered additional troops to join Devens, only three boats were available to ferry soldiers to the Virginia side and so movement was slow. Colonel Edward Baker was ordered to take command of the larger force, totaling 1,640 men. Baker was an inexperienced soldier, but he was also an old Illinois friend of President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln, in fact, had named his second son after Baker. After he had moved west, Baker was elected senator from Oregon. He had turned down a commission as brigadier general, because it would require his resignation from the Senate. An outspoken enemy of any who would compromise with the slaveholding South, he looked forward to an opportunity to prove his point in battle.

Baker ordered his men to form a line of battle in a clearing near the river. Immediately in the rear of his position was 100-foot Ball’s Bluff; a single narrow path led down to the Potomac. More experienced officers worried about a wooded ridge immediately in front of Baker’s line. Confederates on that height would be able to shoot down at the Union soldiers in the clearing below.

Baker ordered his men to form a line of battle in a clearing near the river. Immediately in the rear of his position was 100-foot Ball’s Bluff; a single narrow path led down to the Potomac. More experienced officers worried about a wooded ridge immediately in front of Baker’s line. Confederates on that height would be able to shoot down at the Union soldiers in the clearing below.

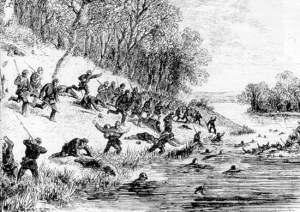

Actually, Confederate units under the command of Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans were slowly arriving on the battlefield and exchanging shots with the Yankees. At 3:00 p.m. the Confederates launched a general assault on the four regiments at Ball’s Bluff. Soon, Evans’s 1,600 Rebel soldiers in wooded cover were pouring shot into Baker’s forces in the open. For three and one-half hours, the Union soldiers held on. Baker was killed around 5:00 p.m. Unable to stand the fire and unable to retreat in an orderly manner, the Yankee formation began to crumble. Some leaped off the bluff in an attempt to reach the river, and many were killed or injured by the fall. Others climbed safely down Ball’s Bluff, but the few boats were swamped by the numbers trying to regain the Maryland side. As the Confederates fired down from the top of the bluff, boats sank and scores drowned in the river. By 7:00 p.m. the battle was virtually over and most Federal survivors were prisoners.

Union losses totaled 49 killed, 158 wounded, and 714 captured or wounded. Confederate casualties amounted to 33 killed, 115 wounded, and one man missing. The obvious disparity in losses was clear to all and trumpeted by the Confederates, while the defeat having occurred so near to Washington ensured that newspaper reporters would quickly spread the news to the rest of the country.

The effects were quickly felt in the north. For Lincoln, Baker’s death was a personal blow. When informed, Lincoln stood stunning and silent for several minutes. He walked slowly back to the executive mansion with bystanders noting tears rolling down his face. Baker was buried in a state funeral attended by the president, vice president, congressional leaders, and the Supreme Court. He immediately became a martyr to the cause of the Union, despite the fact that his inexperience had contributed to the disaster.

Nonetheless, the political establishment was intent on discovering darker motives for the disaster. Although many regular officers blamed Baker, Republicans who favored a hard war policy and the destruction of slavery blamed McClellan and Stone. On 20 December, Congress created the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Representatives from both the Senate and the House of Representatives thus formed a permanent committee to inquire into and investigate how the war was being directed. Investigations were conducted in secret, and the committee was soon persecuting those suspected of having Southern sympathies.

Their first victim was General Charles P. Stone. Witnesses denounced Stone, alleging that he secretly communicated with unnamed Southerners and returned runaway slaves to their owners. He was also blamed for failing to reinforce Baker at Ball’s Bluff. The Committee took their findings to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who ordered Stone relieved of command and arrested on 8 February 1862. Stone was never tried, but enough testimony was released to the newspapers to paint him as a traitor. Stone was released from prison in August 1862, and though he served again, his military career was virtually at an end. Stone’s experience remained an example and warning to Union commanders throughout the remainder of the war.

- Tim J. Watts

Additional Links:

The U.S. Army has a detailed look at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff that was published previously as Ball’s Bluff: An Overview and is now on line. You can find that here.

The Civil War Trust has a webpage dedicated to the Battle of Ball’s Bluff with additional resources, including recent efforts to preserve the historic battlefield from development encroachment. You and find their Ball’s Bluff page here.

The Balls’ Bluff National Cemetery contains 25 burial plots containing the remains of 54 soldiers. Only one, plot #13, is identified as James Allen, a soldier from the 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

The Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority began its Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Restoration program in 2004, to restore the park’s appearance to what it looked like in 1861. You can find more information about those efforts here.

You can read a brief biography of Senator-Colonel Edward Dickinson Baker here.

For further reading:

Farwell, Byron. Ball’s Bluff: A small Battle and Its Long Shadow (1990).

Grimsley, Mark. “The Definition of Disaster.” Civil War Times Illustrated (1989).

Holien, Kim Bernard. Battle at Ball’s Bluff (1985).

Stears, Stephen W. “The Ordeal of General Stone.” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History (1995).

Tap, Bruce. Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War (1998).