Honey Springs was the most important Civil War battle fought in Indian Territory. It preserved Union ownership of Fort Gibson and dealt Confederate forces a blow from which they never fully recovered. It also opened the way for the Federal capture of Fort Smith, Arkansas, and helped justify the recruitment of black regiments by the Union army.

In April 1863, Colonel William A. Phillips and a Union column out of Kansas challenged Confederate authority in Indian Territory by occupying Fort Gibson on the Arkansas River. Confederate Brigadier General Douglas H. Cooper decided to retake that vital post, and he began gathering troops and supplies at Honey Springs, a Confederate depot twenty miles southwest of his objective.

By mid-July, Cooper had massed a mixed force of 6,000 Texans and Indians at Honey Springs. He also had a four-gun battery. Another 3,000 Confederate soldiers under Brigadier General William L. Cabell were enroute from Fort Smith, and Cooper expected them at Honey Springs sometime around 17 July. Once these reinforcements arrived, Cooper planned to advance on Fort Gibson, whose garrison barely numbered more than 3,000 men.

Unfortunately for Confederate hopes, Major General James G. Blunt, the aggressive commander of the Union District of the Frontier, learned of Cooper’s offensive preparations. Blunt realized that he had to smash the enemy at Honey Springs before Cabell arrived or forfeit Fort Gibson. Organizing a field force consisting of 3,000 men and twelve cannon, Blunt forded the Arkansas above Fort Gibson on 15-16 July and followed the Texas Road south. A rainy night march brought the Federals within six and a half miles of Honey Springs by daybreak on 17 July.

Blunt discovered that Cooper had advanced a mile and a half from Honey Springs to meet him at Elk Creek. Cooper took advantage of the timber fringing the north bank of the creek to deploy his Texans and Indians in a sheltered line one and a half miles long, but his position was not as strong as it looked. Blunt’s superiority in artillery offset the Confederates’ superiority in numbers. Furthermore, nearly a quarter of Cooper’s troops lacked serviceable firearms, and their gunpowder was an inferior brand imported from Mexico. An early morning rain turned much of this powder into useless paste, leaving many rebels virtually defenseless.

The battle opened at 10:00 A.M. with a one-hour artillery duel. The Confederates knocked out a Federal 12-pound Napoleon howitzer, but their main opponents responded by disabling a mountain howitzer. Dismounting his cavalry units to fight on foot, Blunt sent them and his infantry to rake Cooper’s line with rapidly delivered small arms fire.

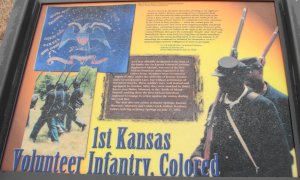

In keeping with his abolitionist principles, Blunt entrusted the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, the first black combat regiment in the Union Army, with holding the center of his line. After nearly two hours of fighting, Blunt directed the 1st Kansas to advance and capture the rebel artillery.

The black soldiers soon found themselves exchanging volleys with the dismounted 20th and 29th Texas Cavalry, posted in support of Cooper’s guns. In the midst of this standoff, the Union 2nd Indian Home Guard Regiment blundered into the 1st Kansas Colored’s field of fire. As the Indians scampered out of the way, the Confederates mistakenly assumed that Blunt’s entire line was giving way. The 29th Texas surged forward with a cheer. The 1st Kansas calmly permitted their opponents to close to twenty-five paces and then unleashed a series of destructive volleys that sent the Texans reeling to the rear without their regimental colors. A jubilant Blunt later reported: “I never saw such fighting as was done by the negro regiment. They fought like veterans, with a coolness and valor that is unsurpassed. They preserved their line perfect throughout the whole engagement and, although in the hottest of the fight, they never once faltered. Too much praise cannot be awarded for their gallantry.”

With the center of the Confederate line shattered beyond repair, Cooper retreated across Elk Creek. Blunt drove the Confederates past Honey Springs and managed to save much of the depot’s stocks of foodstuffs from fires hastily set by his beaten foes. The fighting ended at 2:00 P.M., two hours before Cabell arrived on the scene with his 3,000 men from Fort Smith.

At a loss of seventeen killed and sixty wounded, Blunt had saved Fort Gibson and the Union foothold in Indian Territory. Cooper admitted to 134 killed and wounded and forty-seven captured, but his army had suffered a major blow. Henceforth, Confederate forces in Indian Territory would confine themselves to hit-and-run raids against Union supply trains.

[Written by Gregory J.W. Urwin in the Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History by David S. and Jeanne Heidler. pp. 994-995]

For further reading:

Britton, Wiley. Memoirs of the Rebellion on the Border, 1863 (1993).

Cornish, Dudley Taylor. The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861-1865 (1966).

Fischer, LeRoy H. The Civil War Era in Indian Territory (1974).

Josephy, Alvin M. The Civil War in the American West (1991).

Rampp, Larry C., and Donald L. Rampp. The Civil War in Indian Territory (1975).

Pingback: Honey Springs to get 5,000 square foot visitor center | thisweekinthecivilwar

Pingback: Douglas Hancock Cooper biography | thisweekinthecivilwar

Pingback: Creek Indians in the American Civil War | thisweekinthecivilwar