Manassas Junction, Virginia, was the magnet that attracted the armies of North and South to the banks of Bull Run in July 1861. There two railroads, the Manassas Gap and the Orange & Alexandria, connected thirty miles southwest of Washington, D.C. The Orange & Alexandria was a natural line of advance for a Union army marching southward from Washington, while the Manassas Gap was important because Confederate forces in northern Virginia were divided. Eleven thousand men under Joseph E. Johnston guarded the Shenandoah Valley, while Pierre G.T. Beauregard had 22,000 men at Manassas, Centreville, and Fairfax Court House. The Manassas Gap linked these two armies and made it possible for the South to concentrate its forces wherever the threat was greatest.

Manassas Junction, Virginia, was the magnet that attracted the armies of North and South to the banks of Bull Run in July 1861. There two railroads, the Manassas Gap and the Orange & Alexandria, connected thirty miles southwest of Washington, D.C. The Orange & Alexandria was a natural line of advance for a Union army marching southward from Washington, while the Manassas Gap was important because Confederate forces in northern Virginia were divided. Eleven thousand men under Joseph E. Johnston guarded the Shenandoah Valley, while Pierre G.T. Beauregard had 22,000 men at Manassas, Centreville, and Fairfax Court House. The Manassas Gap linked these two armies and made it possible for the South to concentrate its forces wherever the threat was greatest.

The commanding general of the Union army, Winfield Scott, opposed an offensive into Virginia. Such a move, Scott feared, would only exacerbate sectional tensions. He also had little faith in the ninety-day volunteers that had been gathering around Washington since April. President Abraham Lincoln, however, believed a quick offensive against Manassas was worth a try and ordered Union general Irvin McDowell to organize a 35,000-man army for an operation against Manassas. McDowell shared Scott’s apprehensions over the reliability of his untrained army, but received little sympathy from Lincoln, who admonished, “You are green it is true, but they are green also.”

On 16 July, McDowell’s army began its march out of Washington, but did not reach Fairfax Court House until the evening of the seventeenth, giving the Rebels time to evacuate their advanced outpost there. McDowell’s lead division, under Daniel Tyler, reached Centreville the following day and found Beauregard had already evacuated the town to concentrate behind Bull Run. Tyler then pushed on toward the Bull Run crossings, provoking a sharp skirmish at Blackburn’s Ford, in which the Confederates thrashed Tyler’s force and forced it to withdraw back to Centreville.

Beauregard’s army was now positioned in an eight-mile line that was strong on the right, where the Orange & Alexandria Railroad crossed Bull Run and a series of fords – Mitchell’s, Blackburn’s, and McLean’s – provided convenient crossing points. Alone at the far left was Nathan G. Evan’s brigade overlooking a stone bridge where the Warrenton Turnpike crossed Bull Run.

After the setback at Blackburn’s Ford and reconnaisances demonstrated that Beauregard’s right was too strong to be attacked, McDowell learned that Sudley Ford, a few miles upstream from the stone bridge, was weakly defended and offered a convenient route around the Confederate left. So on 20 July he drew up a battle plan that called for Tyler to march his division west along the Warrenton Turnpike from Centreville toward the stone bridge, followed by David Hunter’s and Samuel Heintzelman’s divisions. Tyler would make a demonstration at the bridge to make Beauregard think the main attack would come there, while Heintzelman and Hunter turned north and moved to Sudley Ford. There they would cross the run at 7:00 and then march south along the Manassas-Sudley Road to crush Beauregard’s left and rear.

It was a good plan. However, its success, like McDowell’s entire campaign, depended upon whether Robert Patterson’s army in the Valley could prevent Johnston from reinforcing Beauregard. Unfortunately for McDowell, Patterson failed, and on 19 July units from Johnston’s army began boarding railroad cars bound for Manassas.

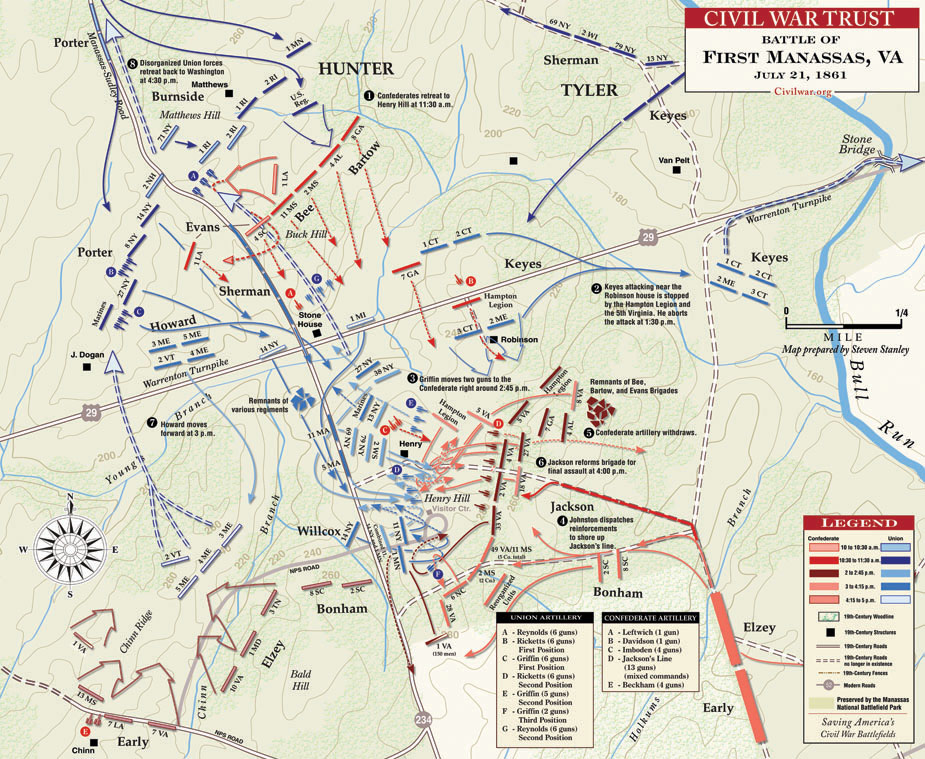

To make matters worse for McDowell, his plan began unraveling from the minute he awoke his men at 2:00 A.M. on 21 July. First, it took an hour for Tyler to get on the road toward the stone bridge. His division then marched at a snail’s pace through the pitch black night until it finally reached the stone bridge at 5:30 A.M. Yet the flanking force had only just begun moving north toward Sudley Ford. At 6 A.M. Tyler began his demonstration by firing an artillery shell across Bull Run; Hunter’s lead brigade under Union General Ambrose Burnside was three miles from Sudley Ford. To make matters worse, Burnside found the road leading to their crossing point was little more than a cart path. Not until 9:30 A.M. – over two hours behind schedule – did the 13,000-man Union flanking force begin crossing Bull Run.

By 8 A.M. Evans had begun to suspect that Tyler’s force at the stone bridge was in fact a feint, a suspicion that was confirmed by a warning from a Confederate signal station: “Look out for your left, you are turned.” Leading 200 men to watch Tyler, Evans led 900 men north to Matthews Hill. By midmorning, the Confederate force on Matthews Hill had swelled to 2,800 with the arrival of Francis Bartow’s and Barnard Bee’s brigades. Their goal was simply to slow down the Federal army and buy time for Beauregard and Johnston to shift forces north to save the Confederate flank.

They bought an hour and a half. By 11:30 A.M. McDowell’s flanking force had crushed the Confederate line on Matthews Hill and sent the Rebels fleeing southward. “Victory! Victory!” an ecstatic McDowell shouted to his men on Matthews Hill. “The day is ours.”

This was not how Beauregard had expected the battle to develop. He had massed his forces on the right so he could attack McDowell’s left and rear and won the approval of Johnston, who had arrived at Manassas on 19 July to assume overall command, for the scheme. Yet, the complex and confusing orders Beauregard issued for the operation and the crisis on Matthews Hill compelled the Southern commanders to abandon this plan and begin shifting forces northward.

The Henry House and the Bull Run Monument on the Manassas Battlefield during a Spring storm. (Photo by Rob Shenk)

Henry Hill, approximately a mile and a half south of Matthews Hill and six miles north of Manassas Junction, would be the key to the battle. If McDowell could capture it, his victory would be complete. But instead of immediately pushing his 18,000 men southward to drive the beaten and disorganized remnants of Evans’s, Bartow’s, and Bee’s commands off Henry Hill, McDowell decided to have only James B. Ricketts’s and Charles Griffin’s batteries fire at the hill from Dogan’s Ridge.

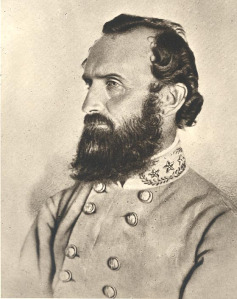

Beauregard and Johnston took full advantage of McDowell’s generosity and began moving reinforcements to Henry Hill. The most important to arrive, Thomas J. Jackson’s brigade, reached the hill around noon. Upon his arrival, Jackson ordered his five regiments of infantry to take cover on the reverse slope of Henry Hill and began rounding up artillery pieces. By the time McDowell decided that he would have to fight for Henry Hill, Jackson had thirteen guns in position.

At around 2 P.M. McDowell ordered the batteries on Dogan’s Ridge to Henry Hill so they could blast Jackson’s line at short range. Ricketts arrived on the hill shortly thereafter and placed his guns south of Henry House, with three hundred yards of open ground between him and Jackson. Griffin’s battery then arrived on Ricketts’s left and a massive duel commenced between their eleven guns and Jackson’s artillery.

The Confederates got the better of the exchange. The Federals were now within range of Jackson’s smoothbore cannon, which they had not been on Dogan’s Ridge, and began taking significant casualties. At the same time, the Confederate line was now too close for the rifled Federal guns to be effective and most of their shells sailed harmlessly over the heads of the Confederates. To make matters worse, McDowell’s efforts to push up infantry support to Ricketts and Griffin were unsuccessful, while Jackson’s line grew stronger by the minute.

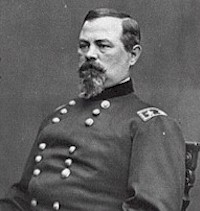

General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson got his nickname at First Bull Run/First Manassas (Library of Congress)

Then, as the guns roared, a legend was born that would fire Southern hearts for years to come. As he rallied his troops behind Jackson’s line, General Barnard Bee beseeched them to “follow me back to where the fighting is.” When they asked there that was, Bee dramatically pointed to his left and shouted, “Yonder stands Jackson like a stone wall; let’s go to his assistance.”

As this was going on, Griffin concluded that a change of tactics was necessary if the Federals were going to break the Confederate line. He then took two guns back to the Sudley Road, turned south, swung around Rickett’s guns, and positioned them on a slight rise to Ricketts’s right. From here, Griffin hoped to hit Jackson’s line with a destructive enfilade fire.

At approximately 3 P.M. Griffin observed an unidentified force moving toward his new position from the right. Although a number of men in this force were wearing blue uniforms, Griffin deduced that it was hostile and ordered his men to load their guns with canister. Just then, McDowell’s chief of artillery, William Barry, told Griffin: “Don’t fire there. Those are your battery support.” Griffin disagreed. “They are Confederates,” he protested, “as certain as the world.” Barry was adamant: “I know they are your battery support.” Griffin reluctantly yielded to the judgment of his superior.

The unidentified force was in fact Confederate William Smith’s battalion of Virginia troops. Seventy yards from Griffin’s position they stopped, lowered their muskets, and fired a devastating volley at the Federal gunners. Smith and Arthur Cummings’s 33d Virginia Infantry Regiment then charged and captured Griffin’s guns. Sensing the tide had turned, Jackson then ordered two of his regiments to charge Ricketts’s battery. Soon Ricketts’s guns were in Rebel hands as well.

Just then McDowell finally managed to get infantry up to his beleaguered artillerymen and a desperate struggle ensued in which the guns changed hands several times. The Federal effort was fatally compromised, however, by McDowell’s failure to commit fully his superior numbers and the fact that, although McDowell managed to get fifteen regiments into the battle, not once did more than two join the fight together. Finally, at around 4 P.M. a spirited charge by two regiments from Confederate colonel Phillip St. George Cocke’s brigade pushed the last Union forces off Henry Hill.

As the battle raged on Henry Hill, McDowell ordered Oliver O. Howard’s brigade to Chinn Ridge. If Howard could seize the ridge, he would be on the western flank of Henry Hill and in an ideal position from which to deliver a decisive stroke against the Confederate line. Just then, however, Arnold Elzey’s and Jubal Early’s brigades, the last Confederate reinforcements from the Shenandoah Valley, reached the battlefield. At 4 P.M. they arrived on Chinn Ridge and crushed Howard’s command. Beauregard then ordered his entire line forward. This convinced McDowell that his army had enough for one day, and at 4:30 P.M. the Federal retreat began.

With their army “more disorganized by victory than that of the United States by defeat,” the Confederate high command was unable to organize an effective pursuit. The Federals were thus able to recross Bull Run well enough, but then a Confederate artillery shell capsized a wagon on the Cub Run Bridge, creating a bottleneck on their line of retreat. Whatever order had existed until then evaporated as panic gripped the exhausted Union troops and the civilians who had come out to Centreville to watch the battle. The retreat degenerated into a chaotic flight back to Washington, and what had been a closely fought battle became a decisive Southern victory. Altogether, nearly 900 men had been killed and over 2,700 wounded, numbers that would pale in comparison to later battles, but nonetheless shocked a nation that had naively expected a relatively bloodless war.

Southerners had anticipated that one victory such as Bull Run would persuade the North to abandon the effort to restore the Union by force. Lincoln, however, made it clear after the battle that he would continue the fight by organizing new armies for the long war to come. Thirteen months later the men in blue and gray would beet again in battle on the plains of Manassas.

Written by Ethan S. Rafus for Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2000) (pp. 312-316).

For further reading:

Davis, William C. Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War (1977).

Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee’s Lieutenant’s: A Study in Command, vol. 1 (1942-1944).

Hennessy, John. The First Battle of Manassas: An End to Innocence July 18-21, 1861 (1989).

Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence Clough Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers (1887-1888).

U.S. War Department. War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (1880-1901).