By Jeffrey S. Williams

Concordia University-St. Paul, Minn.

Written for Dr. David Woodard’s “Readings in American History” class - April 2011.

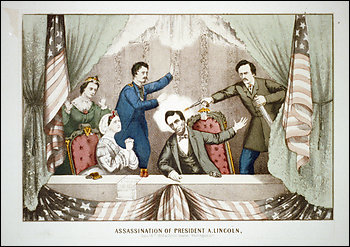

The Northern States were celebrating the end of the Civil War when President Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. shortly after 10 p.m. on April 14, 1865. When the president passed away at 7:22 a.m. the next morning, the celebration abruptly stopped and the nation mourned the passing of its wartime leader.

The Northern States were celebrating the end of the Civil War when President Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. shortly after 10 p.m. on April 14, 1865. When the president passed away at 7:22 a.m. the next morning, the celebration abruptly stopped and the nation mourned the passing of its wartime leader.

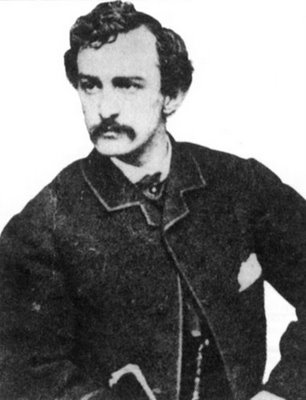

Conflicting eyewitness accounts of nearly every major news story happen frequently and the Lincoln assassination is no exception. Historians still differ on several points surrounding the events of April 1865. Did Laura Keene enter the Presidential Box and cradle Lincoln’s head in her lap (Harbin, 1966)? What was Mary Surratt’s role in the conspiracy (Larson, 2008)? Yet the one thing that all historians seem to agree on is that the man who pulled the trigger at Ford’s Theater on that fateful night was actor John Wilkes Booth.

President Lincoln wasn’t even buried when the first myths about his assassination began to surface.

The first myth was perpetuated by John Wilkes Booth himself. When his effects were brought to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, following the assassin’s death on April 26, 1865, Booth’s personal diary was among the artifacts. He wrote, “I shouted Sic semper before I fired. In jumping broke my leg. I passed all his pickets, rode sixty miles that night, with the bone of my leg tearing the flesh at every jump” (Kauffman, 2004, p. 399). Eyewitnesses immediately corrected the record about when Booth yelled “Sic Semper Tyrannus,” noting that it happened after the shooter landed on the stage. Yet nobody made a reference to Booth breaking his leg at that time (Kauffman, 2004).

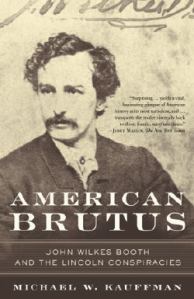

Michael W. Kauffman has studied the Lincoln assassination for three decades and believes that Booth’s broken leg didn’t occur at Ford’s Theater. In American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies (2004), he writes:

Flying through the door to Baptist Alley, Booth thrust his left foot into a stirrup and almost leaped into the saddle. His movement startled the mare, and she pulled out from under him, leaving him twisting with the full weight of his body on that (supposedly broken) left leg. Peanuts Borrows and Major Joseph Stewart both saw Booth’s struggle to throw himself onto the horse, and neither reported anything that suggests he was in pain. Nor did Sergeant Cobb notice any discomfort when Booth approached him to cross the Navy Yard Bridge. Not until Booth reached the tavern in Surrattsville was he clearly suffering from a painful injury. He told John Lloyd that his horse had fallen on him, and he boasted of killing the president. Booth and Herold had switched horses by then. Sergeant Cobb and others were positive that Booth had ridden away on a bright bay mare, and everyone agreed that Herold was on a roan. But outside the city, everyone who encountered them remembered it the other way around. In light of Booth’s broken leg, the switch made perfect sense. An injured man would certainly have preferred the gentle steady gait of a horse like the one Herold had rented. From Lloyd’s to Mudd’s, Booth stayed on that horse, and Herold rode the mare, who was now noticeably lame, with a bad cut on her left front leg. Clearly, she had been involved in an accident. (pp. 273-274).

When the film The Conspirator was released in April 2011, after shooting President Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth falls on the stage and clutches his leg. Even though Kauffman’s book has been on the market for seven years before the film’s release, the myth of Booth’s broken leg is still being perpetuated.

Early Writings

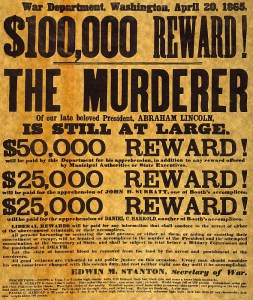

The earliest writings of the Lincoln Assassination were newspaper headlines and official dispatches from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Because of the rapidly moving news cycle and the slow telegraph technology, the early facts about the simultaneous assassination attempt of Secretary of State William H. Seward were incorrect, as the preliminary reports suggested John H. Surratt Jr., was the Seward assailant, instead of Lewis Thornton Powell. It took days before the War Department and the newspapers got the basic facts correct (Kauffman, 2004).

The real story of the assassination and the conspiracy didn’t start coming out until the trial of the conspirators - Mary Surratt, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, Dr. Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlin, Samuel Arnold and Edman Spangler, commenced a month later.

In The Trial of the Assassins and Conspirators at Washington City, D.C., May and June 1865, for the murder of President Lincoln (1865), the complete and unredacted transcript of the trial’s proceedings were published by T.B. Peterson & Brothers, shortly after the execution of Surratt, Atzerodt, Powell and Herold on July 7, 1865. This coincided with the release of the U.S. Army’s heavily edited transcript, The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators (1865), edited by Benn Pitman, the trial’s court reporter.

George Alfred Townsend, a veteran journalist during the Civil War, published the daily reports that he wrote for the New York Herald between April 17 and May 17, 1865, into one volume titled, The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth (1865). All three books are source documents for historians today.

George Alfred Townsend, a veteran journalist during the Civil War, published the daily reports that he wrote for the New York Herald between April 17 and May 17, 1865, into one volume titled, The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth (1865). All three books are source documents for historians today.

Townsend wasn’t satisfied with his coverage. He continued to hunt down leads and acquire information about the assassination throughout the remainder of his life. In 1883, he tracked down his biggest lead when he identified the person responsible for hiding Booth and David Herold for one full week they were on the run. Until then, nobody knew what happened to the pair of fugitives except that anonymous person. After repeated attempts at communication, Thomas A. Jones finally came clean and told his story to Townsend after keeping it a secret for 18 years (Swanson, 2006).

Osborn H.I. Oldroyd, a captain in the 20th Ohio Volunteer Infantry who began collecting Lincoln memorabilia in 1860, opened a small museum at the Abraham Lincoln House in Springfield, Illinois, in 1884. A decade later, he moved the museum to the Petersen House in Washington, D.C., where Lincoln died. Oldroyd ran the Petersen House Museum for three decades before selling his collection to the United States Government, which made it the backbone of their current artifact collection at Ford’s Theater (McAndrew, 2008).

Eleven years after Jones told his story to Townsend, the 74-year old Jones visited the Petersen House, viewed the museum’s artifacts, and examined the room where the late President breathed his last. He then introduced himself to Oldroyd and said, “My name is Thomas A. Jones, and I am the man who cared for and fed Booth and Herold while they were in hiding, after committing the awful deed” (Swanson, 2006, p. 245). Jones died the next year.

Another source document surfaced with the publication of Benjamin Perley Poore’s, Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis (1886), in which the newspaperman vividly recreated the scene in Washington, D.C., during the Civil War, including the Lincoln assassination; Lincoln’s state funeral; and trial of the conspirators; though he didn’t describe the actual hanging of the four conspirators – Surratt, Herold, Atzerodt and Powell. Nonetheless, his descriptions of the events continue to help modern historians paint an accurate picture of the people and places that existed at that time.

The Lincoln Centennial

After the turn of the century, Finis L. Bates wrote, The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth (1907), a largely fabricated story about Booth escaping from the Garrett Farm and fleeing to Enid, Oklahoma. Bates was so convinced that his subject, John St. Helen, was indeed the fugitive assassin that when St. Helen died in 1903, the author took possession of the mummified remains and put them in a traveling display (Bates, 1907). This was the first propagated myth suggesting that Booth might have escaped. The book’s source was an alleged granddaughter of John Wilkes Booth, with no proof of her actual relation to the assassin.

The attention to Bates’s book caught the attention of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation. In a redacted January 10, 1923 letter, BOI Director William J. Burns wrote:

The escape route of John Wilkes Booth and David Herold after the April 14, 1865 assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

I have gone over with considerable interest the volume entitled “The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth” by Finis L. Bates of Memphis, Tennessee, submitted by you. The work contains very strong evidence in support of the old belief that Booth did escape and live many years after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. This Department has no means of verification other than historic works, as the original case was handled by the military authorities. Thank you for bringing this to my attention (BOI, 1923).

This work led to a lawsuit filed by descendents of John Wilkes Booth’s brother, Edwin, to exhume the assassin’s body from Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery for identification purposes hoping to put the myth to rest. After a four-day trial in May 1995, Judge Joseph H.H. Kaplan denied the family’s petition (Wilner, 1996).

The Booth escape myth was propagated as recently as December 23, 2010, when the History Channel ran an hour-long special on Brad Meltzer’s Decoded. Despite numerous attempts by historians to rebut the story with evidence that existed in 1865, this is a story that won’t go away (Kauffman, 2004).

In February 1909, as the nation observed the 100th birthday of President Lincoln, an address was given to the New York Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. It was titled, Lincoln’s Last Hours, written and delivered by Dr. Charles A. Leale, the Army surgeon who attended to Lincoln at Ford’s Theater and the Petersen House. Leale claims that he was the one who, “pronounced my diagnosis and prognosis: ‘His wound is mortal; it is impossible for him to recover.’ This message was telegraphed all over the country” (Leale,, 1909, p. 6). Why did Leale wait for 44 years before recording his memories of that fateful night? It was announced in June 2012 that researchers had discovered his original 1865 report in a box that was stored at the National Archives. It was missing for 147 years. You can read that story here.

On April 17, 1865, a New York newspaper reporter called at my army tent. I invited him in, and expressed my desire to forget all the recent sad events, and to occupy my mind with the exacting present and plans for the future…Recently, several of our Companions expressed the conviction, that history now demands, and that it is my duty to give the detailed facts of President Lincoln’s death as I know them, and in compliance with their request, I this evening for the first time will read a paper on the subject (Leale, 1909, p. 1).

The Leale document is important because it gives historians a first-hand look at the medical care that the president received from the time he was shot until his death the following morning. It also gives historians and surgeons an opportunity to compare older brain trauma techniques with modern medicine.

Dr. Thomas M. Scalea, director of the University of Maryland’s Shock Trauma Center, believes that Lincoln could have survived the shooting if today’s technology had been available. Through Leale’s description of Lincoln’s condition, Scalea and other brain surgeons have determined that the round tore a path through the left side of the brain but did not hit the brainsteam or cross the midline, and stopped before entering the frontal lobes. They concluded that it was a survivable wound by modern standards (Brown, 2007).

After her brother was killed by Sgt. Boston Corbett, Asia Booth Clarke began to write her memoirs of growing up with John Wilkes Booth. Because of the public outrage over the assassination, Asia kept it to herself. Her work was not published until 1938. She solicited memories from her other brothers, Junius Jr., Edwin and Joseph. Edwin replied, “Think no more of him as your brother; he is dead to us now, as he soon must be to all the world, but imagine the boy you loved to be in that better part of his spirit, in another world” (Clarke, 1938, p. 92).

Modern Writings

Samuel J. Seymour was a five-year boy when his godmother took him to the theater that night. When he died on April 13, 1956, one day before the 91st anniversary of the assassination, the last witness to the assassination was gone (McClarey, 2011).

Samuel J. Seymour was a five-year boy when his godmother took him to the theater that night. When he died on April 13, 1956, one day before the 91st anniversary of the assassination, the last witness to the assassination was gone (McClarey, 2011).

Since the passing of Seymour and other witnesses, historians have taken a more objective look at the events of April 1865. The U.S. Government has opened its files to researchers, documents have been located in private collections and more attention has been given to deciphering the accuracy of information.

Michael W. Kauffman’s research has been instrumental in bringing new evidence to light. He has examined eyewitness testimony, government reports, transcripts of the conspirator trials, traced the route of Booth and Herold, including rowing a boat across the Potomac from the same location and in the same manner that the fugitives did. He purchased the rolls of microfilm from the National Archives that contain the 11,000 pages of the Lincoln Assassination Suspects file, and then built a custom database to sort and analyze all of his collected information.

The event-based system I designed was far different from the statistical models used by most historians, and it may actually be unique in the way it applies technology to the study of historical developments. Most important, it works. It brought to the fore new relationships among the plotters, unnoticed patterns in Booth’s behavior, and a fresh significance to events I once considered unimportant. All this has given me a clearer picture of the Booth conspiracy – including incidents no writer had previously noticed…By sorting events over time, I could see how one conspirator fades from the scene while another is shoved into his place. I got a sense of how much work and money went into the plot. I noticed how carefully choreographed the scheme really was. But most surprising of all, I learned how Booth managed to organize and run a dangerous plot – undetected – in the face of unprecedented government paranoia (Kauffman, 2004, pp. xiii-xiv).

It was this event-based system that allowed Kauffman to discover that Booth broke his leg in a riding accident after he crossed the Washington Navy Yard Bridge and before his arrival at the Surratt Tavern (Kauffman, 2004).

In American Brutus (2004), Kauffman spells out Booth’s conspiracy plot in great detail. With dates of meetings and performances, Booths’ travel schedule, money transfers and conversations with people, Kauffman succeeds in outlining the conspiracy with great suspense. However, he gives us only a brief glimpse about the reasoning behind Booth’s plot, and does not fully follow the investigators who were on the trail of the assassin.

In American Brutus (2004), Kauffman spells out Booth’s conspiracy plot in great detail. With dates of meetings and performances, Booths’ travel schedule, money transfers and conversations with people, Kauffman succeeds in outlining the conspiracy with great suspense. However, he gives us only a brief glimpse about the reasoning behind Booth’s plot, and does not fully follow the investigators who were on the trail of the assassin.

James L. Swanson spent nearly his whole life examining the life and death of Abraham Lincoln. Like Kauffman, his research is thorough and conclusions are concrete. While Swanson didn’t put together a significant database of information, he examined many of the same sources as Kauffman, plus looked closer at the newspaper articles from that time period. Swanson published, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer (2006), and picks up where Kauffman left off.

Swanson doesn’t spend much time on Booth’s background or his planning of the conspiracy plot. Swanson focuses on what happened April 14-26, 1865. He shows us what was going on with Booth and Herold during that time, along with the investigators who were examining leads, which eventually led to their apprehension. He also tells of the extreme difficulties that both the fugitives and the investigators faced during that time, and the overall result of Booth’s actions on American history.

John Wilkes Booth did not get what he wanted. Yes, he did enjoy a singular success: he killed Abraham Lincoln. But in every other way, Booth was a failure. He did not prolong the Civil War, inspire the South to fight on, or overturn the verdict of the battlefield, or of free elections. Nor did he confound emancipation, resuscitate slavery, or save the dying antebellum civilization of the Old South. Booth failed to overthrow the federal government by assassinating its highest officials. Indeed, he failed to murder two of the three men he had marked for death on that “moody, tearful night.” He did not become an American hero, but he elevated Lincoln to the American pantheon. And, in his greatest failure, Booth did not survive the manhunt. His was not a suicide mission. He wanted desperately to live, to escape, to bask in the fame and glory he was sure would be his. He got his fame, but at the price of his life (Swanson, 2006, pp. 385-387).

John Wilkes Booth did not get what he wanted. Yes, he did enjoy a singular success: he killed Abraham Lincoln. But in every other way, Booth was a failure. He did not prolong the Civil War, inspire the South to fight on, or overturn the verdict of the battlefield, or of free elections. Nor did he confound emancipation, resuscitate slavery, or save the dying antebellum civilization of the Old South. Booth failed to overthrow the federal government by assassinating its highest officials. Indeed, he failed to murder two of the three men he had marked for death on that “moody, tearful night.” He did not become an American hero, but he elevated Lincoln to the American pantheon. And, in his greatest failure, Booth did not survive the manhunt. His was not a suicide mission. He wanted desperately to live, to escape, to bask in the fame and glory he was sure would be his. He got his fame, but at the price of his life (Swanson, 2006, pp. 385-387).

While the bulk of the historical attention has been on John Wilkes Booth since 1865, two other conspirators had their biographies recently published. Alias Paine: Lewis Thornton Powell, the Mystery Man of the Lincoln Conspiracy (1993), was published by B.J. Ownsbey; and The Assassin’s Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln (2008) was published by Dr. Kate Clifford Larson.

The first part of Larson’s work was a disappointment. A careful reading of Kauffman’s and Swanson’s works, both of which were source documents for The Assassin’s Accomplice, would have corrected some of basic historical inaccuracies, including the Booth claim of breaking his leg at Ford’s Theater. However, she spends more than half of the book discussing the trial of the conspirators, the rules of evidence, brief profiles of the attorneys involved, the sentencing, plea for the writ of habeas corpus, and the hanging of the guilty, which more than makes up for the inadequacies in the beginning.

As a testament to Larson’s professionalism, she admits that she went into the project with preconceived notions of Mary Surratt’s innocence but was swayed by the evidence she uncovered during the trial and in her further research.

Today, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the evidence cannot be ignored. Mary Surratt did indeed keep “the nest that hatched the egg.” She could have chosen not to help Booth, but she decided to assist him in whatever way she could. In providing a warm home, private encouragement, and material support to Abraham Lincoln’s murderer, she offered more than most of Booth’s other supporters. For that, Mary Surratt lost her life and must forever be remembered as the assassin’s accomplice (Larson, 2008, p. 230).

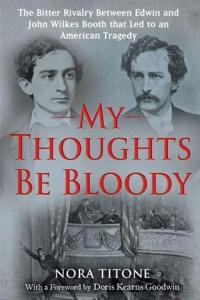

What influenced John Wilkes Booth enough to commit his heinous act? Nora Titone believes that it was a bitter rivalry between John Wilkes and his brother, Edwin, following the death of their father, the famed actor Junius Brutus Booth, that led to the assassination.

In My Thoughts Be Bloody: The Bitter Rivalry Between Edwin and John Wilkes Booth that Led to an American Tragedy (2010), Titone examines the relationship between the two brothers and draws some astonishing conclusions. She compares the careers of the two brothers and discovers that John Wilkes was always jealous of the success and accolades that Edwin received during his career, while Edwin dismissed his younger brother as undisciplined.

In My Thoughts Be Bloody: The Bitter Rivalry Between Edwin and John Wilkes Booth that Led to an American Tragedy (2010), Titone examines the relationship between the two brothers and draws some astonishing conclusions. She compares the careers of the two brothers and discovers that John Wilkes was always jealous of the success and accolades that Edwin received during his career, while Edwin dismissed his younger brother as undisciplined.

Since the assassination, historians have wondered why Secretary of State William H. Seward was a target for assassination while other cabinet members were not. She points out that Secretary Seward invited Edwin Booth to a private dinner on March 11, 1864, which was the beginning of a long friendship between the two men (Titone, 2010).

She also discusses Edwin’s plan for the three acting brothers to have separate territories in the country before the war. Junius Jr., who was already acting in the western United States, would continue to act west of the Mississippi River; Edwin would hold on to the lucrative Northeast; while John Wilkes was relegated to the southern and Midwestern states that were not as profitable. With John Wilkes touring in the south, he sympathized with them (Titone, 2010).

The history I tell is, in large measure, a theatrical history. For three generations, the Booths lived their lives on, and in the shadow of, the stage. To re-create their particular world, it was necessary to gather thousands of pages of primary sources from archives of nineteenth-century American theater history. Reminiscences of the famous clan abound, penned by fellow actors, by legions of journalists, by multitudes of contemporaries and friends. Most important, however, this narrative draws from over one hundred years’ worth of private letters, diaries, memoirs, account books, documents, and journals written by the Booths themselves, as well as from the family’s huge collection of playbills, paintings, statues, photographs, theatrical costumes, dramatic reviews, and stage props. My first debt is to librarians, curators, and archivists who guided me on a five-year search through this rich voluminous record (Titone, 2010, p. 457).

Titone gives us a fresh look at an event that has been well documented and heavily researched. Further investigation into some of the events, like the Seward dinner and the 1863 Draft Riots in New York City that had the entire Booth family, including Edwin and John Wilkes, hiding in fear for their lives, would, perhaps, give us a better indication of the reasons behind the assassination (Titone, 2010).

The Future

Even though nearly a century and a half has passed since the assassination of President Lincoln, historians like Kauffman, Swanson, Larson and Titone are only now scratching the surface in telling the story objectively.

However, little has been written about the involvement of other conspirators like John H. Surratt Jr., who was in Elmira, New York, when Lincoln was killed; George Atzerodt, who failed in his attempt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson; and David Herold, who spent 12 days in hiding with John Wilkes Booth. Other than Dr. Samuel Mudd, little has been written about the lives of Edman Spangler, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O’Laughlin (Kauffman, 2004).

With the release of The Conspirator, questions have been raised about the life of Frederick A. Aiken, Mary Surratt’s attorney. Other minor characters, like Thomas A. Jones, who hid Booth and Herold for seven days while they were fugitives from justice, along with certain myths that continue to be propagated today, are also worthy of further research.

Additional Lincoln Assassination resources can be found here.

References

Brown, D. (2007). Could Modern Medicine have saved Lincoln? The Washington Post. May 21, 2007.

Harbin, B. J. (1966). Laura Keene at the Lincoln Assassination. Educational Theatre Journal. Vol. 18, No. 1 (March, 1966). pp. 47-54.

McAndrew, Tara McClellan. (2008). The First Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum: How a deadbeat saved history. Illinois Times. Nov. 19, 2008.

McClarey, D. R. (2011). Last Eye Witness to the Lincoln Assassination. The American Catholic. February 2011.

Meltzer, B. (2010). Brad Meltzer’s Decoded. History Channel. Aired: Dec. 23, 2010.

Peterson, T.B. (1865). The Trial of the Assassins and Conspirators at Washington City, D.C.,

May and June 1865, for the Murder of President Lincoln. Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson & Brothers.

Pitman, B. (1865). The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trail of the Conspirators. New York: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin.

Poore, B.P. (1886). Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis. Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers.

Redford, R. (Director). The Conspirator [Motion Picture]. United States: American Film Company.

Swanson, J.L. (2006). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer. New York: Harper Collins.

Townsend, G.A. (1865). The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald.

Wilner, C.J. (1996). Reported in the Court of Special Appeals of Maryland, No. 1531, September Term 1995, Virginia Eleanor Humbrecht Kline et. al. v. Green Mount Cemetery, et. al., June 4, 1996.

United States Government. (1923). Letter from William J. Burns, Director of the Bureau of Investigation, Jan. 10, 1923. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Williams is the author of Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War. He devotes a chapter to this subject.

Pingback: Colonel Frederick A. Aiken biography | thisweekinthecivilwar

I have a memory that Mr. Seymour, who you note as having died in 1956, appeared on I’ve got a Secret probably about 1960, when the Civil War centennial was starting. And I have gotten interested in Harry Hawkes, who was on stage when Booth fired his shot. None of several Lincoln websites I once emailed(including Ford’s Theatre) knew a thing about him. I’m curious about who he was.

My great great (maternal) grandparents came to Wash. DC to escape Catholic persecution in Great Britain. I only have their last name: Mitchell. Stories have been passed down that grandfather guarded Mrs. Surratt during her imprisonment- I assume he was a civilian guard? Also, my grandmother used to prepare meals and bring them to Mrs. Surratt.

Our family’s parish was St. Dominics in SW. The Mitchell’s daughter, Ella, married Archibald Hutton and lived in a house he built on F Street. We have always longed to know the names of our British grandparents and what part of Britain they came from?

Having recently viewed the film ‘The Conspirator’ and read articles and biographies about Mary Surratt, Frederick Aiken, John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln assasination I have to say that it would be a novelty and quite refreshing for the film industry to make a movie that is true to the actual historical facts. Indeed, even with conflicting opinions as to some of the details and “myths” surrounding the Lincoln event, accuracy could have been achieved. I thought Robert Redford was better than this; he could have made a better movie with just a little more research.

Michael Kauffman is just another pseudo-intellectual academic egomaniac who is totally caught up in his own bullshit, just like the author of this ridiculous article. Finis Bates never talked to anyone purporting to be Booth’s daughter as the stimulus for his book; he spoke to the escaped J.W.B. himself.

Anyone who reads the testimony of Everett Conger, Willie Jett, and others, who say they got Booth at Garret’s farm, and can’t tell that they are lying through their teeth, has no business writing “history.” Yet, that’s all there are in academia - plagiaristic retards with no sense of discernment; mechanistic, egomanaical robots with the same “myth-breaking” bullshit year after year that passes as “history.” How sad and pathetic they are!

As one of those pseudo-intellectual academic egomaniacs who happened to write the above referenced article, I respectfully disagree.

Pingback: Assassin’s Accomplice: Mary Surratt & the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln (March 2013 discussion) | Bossard Booklovers