by Jeffrey S. Williams

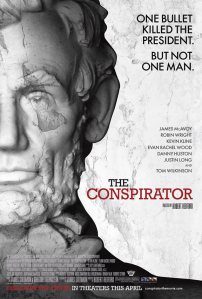

Okay, so we know that the James Solomon/Robert Redford film The Conspirator, now entering its second full weekend, has some inaccuracies to it. What are they?

Here are a few obvious ones that I remember from having watched the film a week ago.

Myth: When David Herold and John Wilkes Booth first arrived at the Surratt Tavern and met with John Lloyd, the film shows Lloyd walking out to the two men on horses, handing the rifles and whiskey and then going back indoors.

Fact: Booth stayed mounted on his horse while Herold dismounted and joined Lloyd inside of the tavern. After Lloyd retrieved the rifles and had a couple of shots of whiskey, they walked out and gave Booth some whiskey before leaving. Herold pitched Lloyd a silver dollar to cover the cost of the alcohol. Booth and Herold were at the tavern for approximately five minutes.

Myth: Booth did not break his leg while jumping from the Presidential box to the stage at Ford’s Theater, as has been commonly claimed.

Fact: According to Michael W. Kauffman, author of American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, “Booth and Herald had switched horses by then. Sergeant Cobb and others were positive that Booth had ridden away on a bright bay mare, and everyone agreed that Herold was on a roan. But outside the city, everyone who encountered them remembered it the other way around. In light of Booth’s broken leg, the switch made perfect sense. An injured man would certainly have preferred the gentle, steady gait of a horse like the one Herold had rented. From Lloyd’s to Mudd’s, Booth stayed on that horse, and Herold rode the mare, who was now noticeably lame, with a bad cut on her left front leg. Clearly, she had been involved in an accident.” Kauffman also states that the first reference to the fall at the theater came from Booth’s own diary entry written days after the incident. In the same entry, Booth writes that he yelled, “Sic Semper Tyrannus” BEFORE he shot President Lincoln, which, according to eyewitness accounts, was yelled after he landed on the stage.

In James L. Swanson’s Manhunt: The 12-day chase for Lincoln’s killer, Herold told Dr. Samuel Mudd that, “one of their horses had fallen, the man claimed, throwing the rider and breaking his leg.”

In James L. Swanson’s Manhunt: The 12-day chase for Lincoln’s killer, Herold told Dr. Samuel Mudd that, “one of their horses had fallen, the man claimed, throwing the rider and breaking his leg.”

Myth: Mary Surratt was put into a prison cell at the Washington Arsenal right after her capture, according to the film.

Fact: She was held at the Old Capitol Prison, currently the location of the U.S. Supreme Court building and formerly the site of the hanging of Andersonville prison camp commander, Henry Wirz, for thirteen days, before being transferred to the Arsenal. She was not at the Arsenal at the beginning of her incarceration but was tried and executed there.

Myth: The Washington Arsenal has a moat.

Fact: The Washington Arsenal was located on Greenleaf’s Point (also known as “Buzzard Point”) surrounded on three sides by the Anacostia River and the Washington Channel. It is currently the site of Fort McNair and the National War College.

Myth: Mary Surratt was unveiled during the trial.

Fact: With the exception of her plea, she was veiled the whole time, including when her daughter, Anna, was on the stand. It may make for a good Hollywood portrayal to have the heroine unveiled during her trial but it is far from historically accurate.

Myth: Mary Surratt wasn’t guilty of her role in the conspiracy.

Fact: This is the whole crux of the debate that has existed since July 7, 1865. The fact is when the detectives first searched the boarding house, Surratt herself was said to exclaim, “For God’s sake! Let them come in. I expected the house to be searched” (Swanson, 119). The movie excluded a lot of other testimony which gave more conclusive proof of Surratt’s guilt and failed to include that. The film IS correct in asserting Reverdy Johnson’s plea that the trial was unconstitutional because she was a civilian being tried in front of a military tribunal, which was the heart of Johnson’s argument throughout the trial, but the defense team examined numerous witnesses which only further concluded Surratt’s guilt. In fact, while trying to portray her as a pious Catholic church-goer, her defense team called up five priests, none of whom could testify that they knew her for any length of time. In essence, her own defense team unknowingly worked against her.

Myth: A secret message was delivered to John Surratt appealing to his mother’s aid.

Fact: This seems quite far-fetched. It is inconceivable that a message could be sent and received to a person on the run in Canada in the course of 12-hours even using the most modern transportation system at that time. This was most-likely a made-up scene to give intrigue to the film.

Myth: The steam locomotive in the film was the same type that was used in the Lincoln Funeral Train.

Fact: This is partially true. It is a similar reproduction and considering the number of years that have passed, would be nearly impossible to reproduce while keeping the film on-time and on-budget. (The Strasbourg Railroad in Strasbourg, Pennsylvania, often makes reproduction steam locomotives for use

in movies – including the one used in the Will Smith film, Wild Wild West.) The Lincoln Funeral Train was pulled by

4-4-0 wood-burning steam locomotives. From Washington to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania - the train was pulled by B&O Railroad locomotive No. 238 with it’s sister engine No. 239 running ten minutes ahead as the advance. From Harrisburg to Jersey City, N.J., the train was pulled by Pennsylvania Railroad locomotive No. 331. The funeral car and Pullman business car were ferried across the river to New York City. From NYC to Albany, N.Y. it was pulled by the “Union” of the Hudson Railroad with the “Constitution” in advance. The Albany to Erie, Pennsylvania leg had the New York Central’s “Dean Richmond” at the helm, though another locomotive might have switched in Buffalo. The next leg was from Erie to Cleveland, Ohio, the duty fell to the Cleveland, Painsville and Ashtabula Railroad’s “William Case.” The “Nashville” of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad took the train from Cleveland to Columbus with the “Louisville” in advance. I’m not sure at this point which locomotive took the train to Lafayette, Indiana, but that’s where the “Persian” of the New Albany and Chicago railroad took over on the journey to Michigan City, Indiana. From Michigan City to Chicago, the Michigan Central railroad’s “Ranger” took the lead. The final leg from Chicago to Springfield and Lincoln’s final resting place was led by the Chicago and Alton’s engine No. 58 with engine No. 40 in advance. The train in the film appeared to be a coal-burner of a later vintage than any of these locomotives. I’ll post more information on the Lincoln Funeral Train at a later date.

Myth: Frederick Aiken was a young idealist unprepared for the U.S. government’s seeming disregard of Surratt’s rights.

Fact: According to Kate Clifford Larson, author of Assassin’s Accomplice, “In reality, Aiken and [John] Clampitt, convinced of their duty to defend Mary to the best of their abilities, lacked experience as trial attorneys and were left to defend her against great odds. But some of that responsibility must be placed squarely with Senator Reverdy Johnson. His actions may have ultimately doomed her. From my perspective, she did little to aid her own defense, and an attorney can only do so much if the client is not cooperative. Indeed, it was later reported that Aitken and Clampitt were frustrated by Mary’s silence.” While little information currently exists about the biography of Frederick Aiken, the stuff that we do have suggests that he was not necessarily a young pro-Union idealist. He was known to have been at-odds with Lincoln and his administration long before he was chosen as Mary Surratt’s attorney by Reverdy Johnson. However, more research needs to be done on Aiken’s biography.

Myth: There were no doctors present at Ford’s Theater.

Fact: Dr. Charles Leale, a 24-year-old Army surgeon, attended the performance that night and was the first to reach the Presidential box to attend to the fatally wounded President. Because he was the first attending physician on the scene, he took the lead in patient care over all the other physicians who were in attendance that night. Dr. Charles Taft was also at Ford’s that night and became the second to reach Lincoln. Taft deferred to Leale at all phases. It was Leale who decided that Lincoln would not survive the trip to the White House on the rutted roads and opted for the boarding house instead. It was Leale’s suggestion that the President be moved out of the theater to the boarding house across the street (the first boarding house was locked and the Petersen House next door was chosen by Leale instead). The other doctors arrived later, but Lincoln was already under the care of two trained medical professionals.

Myth: General Grant and his family were heading to Philadelphia.

Fact: General Grant was heading to his house at 309 Wood Street in Burlington, New Jersey, a house he bought in 1864. The film was correct in that Charles Dana, the Assistant Secretary of War, sent the telegraph to Philadelphia. Uninformed movie-goers might interpret this to mean that Grant’s destination was Philadelphia, which was not the case.

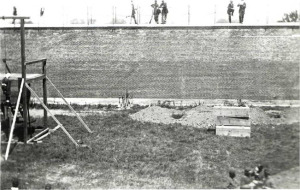

Another thing that the film got wrong was the “sterilized” look. Everything was too clean. Hey, this took place at the end of four years of war. The uniforms were not new. They were well-worn, torn and dirty. I can tell you that as a long-time Civil War reenactor, my uniform is well-worn, torn and dirty. Every reenactor goes through that, and we are clean by Civil War standards as happy “weekend warriors” who don’t live, march and sleep in the same clothing for weeks on end. If you want an accurate portrayal in the film, make sure that the clothes are worn BEFORE shooting begins, and the dust is everywhere. I noticed that in the courtroom scene, they are thick on the cigar smoke. Is this to cover up a lack of dust? But it gets worse - even the graves are perfectly dug. Even Alexander Gardner, who (thankfully) they properly portrayed in the film, took photos of the three graves. The coffin position was correct in the film, but the dirt taken out of the ground was piled too neatly. This is contrary to the photograph that Gardner took July 7, 1865.

There were things that the film got right.

- The casting was extraordinary, minus the miscast Booth, who didn’t seem to fit in despite having such a prominent role in the actual plot.

- The reenactors were used correctly. Unlike other period films with mis-cast reenactors, they blended into the scenery like they belonged there (which they did).

- Secretary of State Seward’s assassination attempt by Louis Powell was correct. Seward was at home recovering from a carriage accident and had a metal brace connected to him that saved his life. Secretary of War Stanton left Seward’s house an hour before the assassination attempt happened.

- Reverdy Johnson was a pro-Confederate Maryland U.S. Senator.

If you do go to see The Conspirator, remember to separate the fact from fiction. Mary Surratt was tried, convicted and hanged - probably with good reason.

Jeffrey S. Williams is the author of Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War, and a member of the Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force. He holds a B.A. in History from Concordia University-St. Paul, and is currently pursuing his M.A. in History at St. Cloud State University.

Pingback: The Conspirator [Movie Review] | thisweekinthecivilwar

I saw The Conspirator recently and liked it very much, I was especially interested in it because my great grandfather was one of the soldiers that guarded her during her time in prison. He also was required to march her to the gallows. This troubled him very much because he felt she was not guilty. His name was Alexander Barber. My mother was raised in his home and over heard him talk about his experiences in the war when other soldiers visited in his home.

I find it hard to believe that the soldiers on station in Washington DC at war’s end would not have access to uniforms in good condition. Obviously they were not the same ones they put on four years earlier. And it’s much easier to knock a good movie than make it! Try raising the finance in Hollywood for something that has no love interest and other mindless stuff that appeals to the masses.

Great article. I was interested in seeing the film, but have had a debate with mother, who is now unfortunately convinced by this fictional somewhat based on an actual event film that Mary Surratt was framed. Mrs. Surratt’s actions did meet a legal standard of guilty for that era — I doubt in any modern era she would have been sentenced to death, instead of receiving a long and deserved prison sentence, just as I don’t think Julius and Ethel Rosenberg would be executed for treason today.

From what I recall, Mrs. Surratt took firearms out to her tavern that she rented out, and also lied by claiming that she didn’t know Louis Powell/Paine when he came to her door after attacking Seward. It seems that Powell may have made later claims that Mrs. Surratt wasn’t involved, simply due to the pleas of her daughter.

My mother also mentioned that in the film, the boarder, Lewis Weichmann, is shaded in as an accomplice to the conspiracy, which also doesn’t have much credible evidence supporting that conclusion. And kudos if Alexander Gardner, the more prolific photographer of that era, is getting some recognition, instead of the overly lauded Matthew Brady. While it’s nice to see a historical event based film instead of all those damned pirate films, the basic principle applies — don’t believe everything you see on film or television.

Even though I am not a historian, I have read much on the Lincoln assassination & the conspirators that planned his first, kinapping and secondly, murder.

Though the film seems to lean on the side of Mary Surratt knowing about the plan to kidnap Lincoln, it leans towards making her sound like she didn’t know about the plan to murder Lincoln. Personally, I tend to think she was guilty — spending so much time talking to Booth, expecting the police to come to question her etc. & taking the shooting irons & whisky to Lloyd. I guess we’ll never know what full facts.

A fascinating story — well done movie, I think.

Pingback: » Die Lincoln Verschwörung (2010) - Historienschinken -

I noticed how grand her boarding house looked. In real life, it is no where near as big.

Just saw this film.. finally. My takeaway was that her guilt or innocence mattered less than the manner in which she was tried.. and the barbarity of all killings, including executions by the state. Similar to what we still face today with Gitmo and al Qaeda.

Is there ever a “good reason” for the state to kill someone?

I would have to say that Booth DID break his leg in the jump. He wrote that in his diary. Wouldn’t that be the best historical evidence?

“I struck boldly and not as the papers say. I walked with a firm step through a thousand of his friends, was stopped, but pushed on. A Col- [Colonel] was at his side. I shouted Sic semper [“Thus always to tyrants”] before I fired. In jumping broke my leg. I passed all his pickets, rode sixty miles that night with the bones of my leg tearing the flesh at every jump.Thus always to tyrants”

Not necessarily due to a couple of things. 1. Could he have WANTED it to sound that way to try to make himself sound braver than he is? 2. When you are in pain and have the adrenaline rush from being a fugitive, a lot of times the mind plays tricks, making everything jumble together. Could Booth have gotten things out of order because of the panic? 3. Would the historical narrative change if Booth would have admitted that he fell off his horse? Yes, it would have. I think taken together, Booth wanting to sound braver, not admit that he was a poor horseman, and got the sequence of events mixed up because of adrenaline and pain is a plausible explanation for why he wrote it wrong.

The eyewitness accounts of people at the Theater mention how he ran past them quickly and jumped onto his horse. You don’t run fast and jump on a horse when you have a broken foot, even with the adrenaline rush. The sentry at the gate at the river said he was on one color horse and the barkeep at the Surratt Tavern said he was on another. David Herold admitted that his partner was pinned underneath a horse - he told this to the barkeep at the tavern and to Dr. Samuel Mudd. Medical evidence also suggests that the broken foot was more in-line with a horse accident rather than jumping from an 11-foot balcony. I trust the accounts of the eyewitnesses, sentry, barkeep, Mudd and Harold more than I trust what Booth wrote in his diary. The others are also historical accounts. That also goes for when he shouted sic, semper, tyrannus - he states in his diary that it was BEFORE he shot Lincoln, but numerous eyewitness accounts state that it was AFTER he shot Lincoln.

What about the idea that the committee leaned towards life in prison, but the Secretary of War convinced them otherwise? Also, did the attorney manage to get a writ, only to be denied by the President?