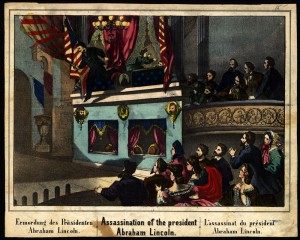

President Abraham Lincoln knew that the possibility of his assassination was a constant possibility. In his desk drawer was an envelope marked “Assassination,” full of threats written to him during his administration. On the evening of Good Friday, 14 April 1865, Lincoln attended a production of Our American Cousin starring Laura Keene at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., with his wife, Mary. The Lincolns enjoyed the theater and went as often as possible. A young army officer named Henry R. Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, daughter of Senator Ira T. Harris of New York, accompanied them.

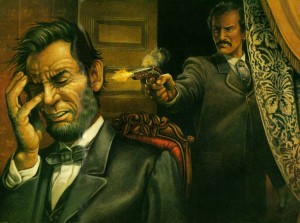

Ironically, the theater was full that evening because many expected Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife to be in attendance. While Lincoln was a familiar sight, Grant was not. The Grants canceled at the last moment to travel out of town. The performance had begun at 7:45 p.m., and the Lincolns arrived late, at 8:15. Two hours later, at approximately 10:15, as he sat in his presidential box, Lincoln was shot once in the back of the head at close range by a .44-caliber single-shot muzzle-loading derringer fired by John Wilkes Booth.

Ironically, the theater was full that evening because many expected Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife to be in attendance. While Lincoln was a familiar sight, Grant was not. The Grants canceled at the last moment to travel out of town. The performance had begun at 7:45 p.m., and the Lincolns arrived late, at 8:15. Two hours later, at approximately 10:15, as he sat in his presidential box, Lincoln was shot once in the back of the head at close range by a .44-caliber single-shot muzzle-loading derringer fired by John Wilkes Booth.

Unlike other presidential assassins, Booth was a prominent figure. One of the best-known actors of his time, he was the son of famed tragedian Junius Brutus Booth and brother of Edwin Booth, America’s best-known Shakespearean actor. Booth himself had performed in front of Lincoln.

The bullet entered near the president’s left ear and lodged behind his right eye. Rathbone rushed the assassin and was wounded in the left arm by a large knife brandished by Booth. Several hundred theater-goers heard Booth utter “sic semper tyrannis” (“so always to tyrants”), the motto on the state flag of Virginia, and saw him leap almost twelve feet to the stage floor below, breaking his right leg in the process. In the confusion, many in the audience thought for a moment that this was part of the theatrical production. Despite his injury, Booth was able to escape out a rear door of the theater.

The bullet entered near the president’s left ear and lodged behind his right eye. Rathbone rushed the assassin and was wounded in the left arm by a large knife brandished by Booth. Several hundred theater-goers heard Booth utter “sic semper tyrannis” (“so always to tyrants”), the motto on the state flag of Virginia, and saw him leap almost twelve feet to the stage floor below, breaking his right leg in the process. In the confusion, many in the audience thought for a moment that this was part of the theatrical production. Despite his injury, Booth was able to escape out a rear door of the theater.

At almost the same time, co-conspirator Lewis Paine (whose real name was Lewis T. Powell) was breaking into the home of Secretary of State William H. Seward, where he attacked the secretary with a knife but failed to kill him. A neck collar the bedridden secretary was wearing at the time, the result of a carriage accident he had suffered several days earlier, saved Seward’s life. Paine also fled into the night.

The mortally wounded president was immediately attended to by an army surgeon, Dr. Charles Leale, and two other doctors in attendance, Dr. Charles A. Taft, also an army surgeon, and Dr. A.F.A. King, of Washington. They ordered the wounded president transported to a bedroom across the street in the Petersen house, where six soldiers carried him. The sixteenth president of the United States died at 7:22 the following morning. The Reverend Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, was in attendance and offered a prayer. Standing at Lincoln’s bedside, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton exclaimed, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

The mortally wounded president was immediately attended to by an army surgeon, Dr. Charles Leale, and two other doctors in attendance, Dr. Charles A. Taft, also an army surgeon, and Dr. A.F.A. King, of Washington. They ordered the wounded president transported to a bedroom across the street in the Petersen house, where six soldiers carried him. The sixteenth president of the United States died at 7:22 the following morning. The Reverend Phineas D. Gurley, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, was in attendance and offered a prayer. Standing at Lincoln’s bedside, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton exclaimed, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

On 18 April, thousands viewed the remains of the president in the East Room of the White House. Funeral services were held there the next day. On 20 April, thousands more viewed the casket in the rotunda of the Capitol. On 21 April, Lincoln’s body began the long 1,700-mile journey back home to Illinois on board a funeral train that traveled through Philadelphia, New York, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Chicago. He was laid to rest on 4 May at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

After the shooting, Booth rendezvoused with co-conspirator David Herold, and together they traveled to the Surratt Tavern, a gathering spot for Confederate operatives in Surrattsville (modern Clinton), Maryland. The tavern sat about a dozen miles from Ford’s Theater and was owned by Mary Surratt. Her son John Surratt, Jr., was a known Confederate agent. Booth and Herold next traveled to the home of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd just outside Bryantown, Maryland, fifteen miles south of the Surratt Tavern. Here in the early morning hours of 15 April, Dr. Mudd set Booth’s broken leg. Mudd’s role in the conspiracy has been the object of much debate. Mudd claimed to have known nothing of the assassination and said that Booth wore a false beard when he set his leg. Much circumstantial evidence tends to cast doubt on Mudd’s claims.

Leaving Mudd’s, the pair traveled to the home of Samuel Cox near Bel Alton, Maryland, where they hid in a pine thicket for several days. They were provided a rowboat with which to cross the Potomac River into Virginia by Cox’s foster brother Thomas A. Jones, a Confederate spy and blockade runner. In Virginia they hid out near Port Royal in a tobacco barn owned by Richard Garrett. It was there that Booth and Herold were cornered by Federal troops on 26 April. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused to give up, and the barn was set on fire. Booth was shot to death by soldier Boston Corbett, who fired against orders through a small opening in the barn wall.

After Booth’s death, details began to emerge about the chain of events that led up to the assassination of President Lincoln. Late in 1864 Booth had devised a plot to kidnap the president and exchange him for Confederate prisoners of war. In August 1864, General Grant had terminated prisoner exchanges, reasoning that the numerical superiority of Union troops made it unnecessary. Booth had apparently felt that extreme steps were necessary to replenish Confederate ranks.

Besides Herold, Booth’s group of conspirators in the kidnapping plot included Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlin, former schoolmates who had fought for the Confederacy. Lewis Paine was a Confederate deserter from Florida. George Atzerodt was a German immigrant whose role was to ferry the kidnappers across the Potomac River. John Surratt was a Confederate agent and courier. The conspirators met frequently at the boarding house of Mrs. Mary Surratt, mother of John, in the city of Washington.

After at least two failed attempts to kidnap Lincoln in January and March 1865, Booth ran out of time. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on 9 April signaling an end to the war in Virginia. In a rage, Booth changed his kidnapping plot to murder. He awaited his opportunity, and his chance came on 14 April when he picked up his mail at Ford’s Theatre and discovered that the president and Mrs. Lincoln would be attending that evening. Quickly searching out his former group of kidnap conspirators, he found that Paine, Herold, and Atzerodt were available. Arnold and O’Laughlin had tired of Booth’s schemes and left town. They quickly drafted a plan that called for Paine to murder Secretary of State Seward and Atzerodt to murder Vice President Johnson, while Booth would shoot Lincoln. The entire government would be brought down at once. As it happened, only Booth would succeed in carrying out his part of the scheme. Paine wounded Seward but did not kill him. Atzerodt got drunk and never even approached Johnson.

The Assassination Conspirators Hang - from left: Mary E. Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold. Photo by Alexander Gardner.

Hundreds of individuals were arrested and questioned, but most were eventually released. On 10 May, a military tribunal was convened to try Herold, Mary Surratt, Lewis Paine, George Atzerodt, Edman Spangler, Michael O’Laughlin, Samuel Arnold and Samuel Mudd for their roles in the conspiracy to assassinate the president. (John Surratt would evade capture for two years and would be released when his trial ended in a hung jury.) All were convicted, and on 7 July Atzerodt, Herold, Paine, and Mary Surratt were hanged for their part in the assassination. Historians have long debated whether Mary Surratt deserved the death penalty, for her role might have been marginal. The remaining defendant all received life sentences, except Spangler, who was sentenced to six years in prison for helping Booth escape from Ford’s Theatre. President Johnson pardoned all in 1869 except O’Laughlin, who had died of yellow fever in prison in 1867.

In the years since the assassination, a number of theories have arisen regarding additional individuals who possibly may have been involved in the plot to kill Lincoln. The government clearly believed that Lincoln was simply the victim of a conspiracy organized by Booth, and that all participants were identified. A number of works would support this theme, among them The Great American Myth by George S. Bryan (1940, reprinted in 1990); The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and its Expiation by David M. DeWitt (1909); and The Death of Lincoln: The Story of Booth’s Plot, His Deed, and the Penalty by Clara Laughlin (1909).

Vice-president Andrew Johnson was an early suspect. There is evidence that Booth and Johnson may have known one another, but a congressional investigation looked into the relationship and found nothing suspicious. Mary Todd Lincoln for years continued to suspect that the vice-president had a part in her husband’s death.

Chemist and armchair historian Otto Eisenschiml in his 1937 work, Why Was Lincoln Murdered, points blame at Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Stanton, according to Eisenschiml, did not feel that Lincoln was prepared to go far enough to punish the South in his Reconstruction policies and so sought to remove him from office by any means. According to this theory, Stanton maneuvered Grant away from Ford’s Theater on the fateful evening, because Grant’s presence would require military guards. He refused to allow Major Thomas T. Eckert to accompany the Lincolns to the theater, even after Lincoln had personally requested him. He refused to notify guards at the Navy Yard Bridge, which Booth used as an escape route. He tampered with Booth’s diary and may have been responsible for arranging to have Booth shot before he could be brought to trial.

Later research would first support and later contradict Eisenschiml’s position. The Web of Conspiracy: The Complete Story of the Men Who Murdered Abraham Lincoln by Theodore Roscoe (1959), and The Lincoln Conspiracy

by David Balsinger and Charles E. Seller (1977) expanded on Eisenschiml’s thesis, but William Hanschett’s landmark work The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies (1983) demolished it. Hanschett examines the Eisenschiml thesis point by point and finds numerous errors and distortions of fact. Stephen B. Oates’s Abraham Lincoln: The Man behind the Myths (1998) finds that many of Stanton’s acts at the time have innocent explanations or were mere coincidence. Stanton is today no longer considered a suspect in the Lincoln assassination.

Several recent publications have argued that a broader Confederate conspiracy existed in the assassination of President Lincoln. The most prominent of these are Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln by William A. Tidwell, James O. Hall and David Winfred Gaddy (1988); Tidwell’s April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War (1995); and Wilkes Booth Came to Washington by Larry Starkey (1976). According to this theory, Lincoln was considered a war target and fair game for assassination. Papers found on the body of Ulric Dahlgren after his part in Judson Kilpatrick’s failed raid on Richmond allegedly outlined a plan approved by Lincoln to murder Jefferson Davis, though there is some question as to their authenticity. Whether the Confederate government directed Booth’s plans, was aware of them, or whether Booth worked alone remains unclear.

- Steven Fisher

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1192-1196]

Click here for a list of additional Lincoln Assassination resources.