The small Virginia town of Appomattox Court House, ninety miles west of Richmond, was the site of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia to Federal forces on 9 April 1865. A twelve-day campaign drew both armies away from the metropolitan area of the Confederate capital, before the Confederate army finally gave in to increasing Federal pressure and superior numbers. The Confederate surrender was the end of the Civil War in Virginia and marked the beginning of the end of the war across the South.

The Federal forces that gathered for the spring campaign in 1865 numbered just over 76,000 and were under the overall command of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. Grant’s army consisted of the Army of the Potomac, under Major General George G. Meade, the Army of the Shenandoah, under Major General Philip H. Sheridan, and the Army of the James, under Major General E.O.C. Ord. The Confederate forces of approximately 57,800 were led by General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. The Confederate ranks also included soldiers from the Department of Richmond, under Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, and the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, under Brigadier General Henry Wise.

The Campaign

The Appomattox Campaign began on 29 March 1865. Federal and Confederate forces had been entrenched around Petersburg since late spring 1864, but both sides expected decisive action in 1865.

The immediate goal of the Federal army at this time was to capture the Southside Railroad to cut off Petersburg from its major supply route. The larger objective of the campaign was to force Lee to stretch his thin forces to the point where the Confederates would have to abandon Petersburg and Richmond. Accordingly, Grant sent infantry and cavalry forces to the southwest of Petersburg, planning to flank and draw the Confederate forces out of their entrenchments. In the final days of March, several actions took place at Quaker Road, White Oak Road, and Dinwiddie Court House, all of which were preliminary to the decisive battle at Five Forks on 1 April.

The Confederate defeat at Five Forks left Petersburg and Richmond vulnerable to the strong Federal forces that now circled the two cities from the south. Lee advised President Jefferson Davis that the Confederate government should abandon the capital immediately, and on 2 April, a stream of political and civilian refugees began to pour out of the city. Petersburg was also evacuated that day, and Federal forces occupied both cities on 3 April. As for the Confederate army, its best hope was to move southwest out of Virginia and attempt to join Joseph Johnston’s forces in North Carolina. With this goal, Lee’s forces began a westward retreat, trying to stay ahead of the rapidly advancing Federal army.

The Confederate defeat at Five Forks left Petersburg and Richmond vulnerable to the strong Federal forces that now circled the two cities from the south. Lee advised President Jefferson Davis that the Confederate government should abandon the capital immediately, and on 2 April, a stream of political and civilian refugees began to pour out of the city. Petersburg was also evacuated that day, and Federal forces occupied both cities on 3 April. As for the Confederate army, its best hope was to move southwest out of Virginia and attempt to join Joseph Johnston’s forces in North Carolina. With this goal, Lee’s forces began a westward retreat, trying to stay ahead of the rapidly advancing Federal army.

In addition to meeting up with Johnston, Lee had the more immediate problem of feeding and supplying his troops. Over the next three days, the army moved west, toward Amelia Court House, engaging with Federal forces at Sutherland Station, Namozine Church, and Jetersville. Supplies were to be sent from Richmond to meet the army at Amelia. When the army arrived on 4 April however, there was no food waiting - ordnance and other supplies had been sent instead. The delay caused by this error cost Lee his small lead on the Federal forces. He was forced to redirect his army toward the next potential supply depot, Farmville.

On 6 April, as Lee’s army neared Farmville another fierce battle took place at Sayler’s Creek, culminating in another Confederate defeat. Some soldiers did receive rations at Farmville on 7 April, but the appearance of Federal troops forced the Confederates to move on, abandoning their supplies. Lee hoped that by crossing the Appomattox River and destroying the bridges he could cut off the Federal pursuit. One bridge was not destroyed in time, however, and the Federals were able to maintain their chase across the river. The Confederates had to keep going, fighting a holding action at Cumberland Church and making a hard night march toward their next supply stop, Appomattox Station. Meanwhile, fast-moving Federal cavalry remained south of the river and kept moving west to head off the Confederate forces.

By 7 April, Grant had begun to think that the Confederates might consider surrendering. He was told that the captured General Ewell claimed that the Confederates should have surrendered earlier, when they could have negotiated better terms. By the 7th, Grant had also been informed of Sheridan’s intention to capture several Confederate supply trains waiting at Appomattox Station. As a result of this information, Grant opened communications with Lee by sending a note requesting the surrender of his army, since further Confederate resistance appeared futile.

Lee was also considering his options, which were few and difficult. Ten days into this campaign, Lee’s army was rapidly losing its effectiveness. Lack of proper nourishment and hard marching were taking their toll physically, and the men began to drop from exhaustion. Morale was plummeting; the precarious position of the Confederacy had to have been evident to soldiers with the loss of Richmond, the flight of the government, and the Army’s own difficult campaign all combining to present a bleak prospect for the future. Soldiers began to desert in large numbers.

Lee was also considering his options, which were few and difficult. Ten days into this campaign, Lee’s army was rapidly losing its effectiveness. Lack of proper nourishment and hard marching were taking their toll physically, and the men began to drop from exhaustion. Morale was plummeting; the precarious position of the Confederacy had to have been evident to soldiers with the loss of Richmond, the flight of the government, and the Army’s own difficult campaign all combining to present a bleak prospect for the future. Soldiers began to desert in large numbers.

Surrender was a painful choice, but Lee’s other options were hardly more palatable. Should they not get through to North Carolina, the Army of Northern Virginia could engage in one final bloody battle that would probably destroy it completely; alternatively, soldiers could be ordered to return to their states to carry on the war by other means. That night, Lee responded to Grant’s note, saying only that in the interest of avoiding more bloodshed, he would like to know what terms Grant would offer.

Grant’s next communication, received by Lee on 8 April, stated that the only condition upon which he would insist was that the soldiers be disqualified from taking up arms against the U.S. government until properly exchanged. In this message, grant offered to meet with Lee or a representative to arrange the surrender.

Despite the formidable realities of his situation, Lee replied to Grant that perhaps the Federal commander had misunderstood; he still did not think that “the emergency has risen to call for the surrender of this Army” and had not proposed to arrange a surrender with his last note. However, he was willing to discuss peace terms generally and offered to meet with Grant the following morning at 10:00 a.m. Grant’s response, received on the morning of 9 April, was brief - he was not authorized to treat generally for peace, only for the surrender of the army, so there would be no point in meeting unless it was to discuss surrender.

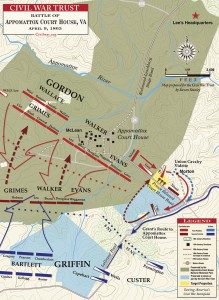

On the night of 8 April, Lee and his corps commanders decided to make one final attempt to break through the next morning. In their front, General John Gordon’s Confederate infantry division, supported by Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry, faced only Federal cavalry and would make the initial assault. A breakthrough here was considered the only feasible option. James Longstreet’s corps held the Confederate rear.

Unknown to the Confederates, however, Federal infantry was marching hard through that night to join Sheridan’s cavalry and reinforce their precarious position. More Federal infantry rapidly approached the Confederate rear guard. Once the forces were engaged very early on 9 April, Gordon sent word back to Lee that he did not think he could hold his position without support.

While waiting for the expected 10:00 a.m. meeting with Grant, Lee informally polled some of his commanders for their opinions on the situation. Longstreet and William Mahone counseled surrender. E. Porter Alexander opposed that view and encouraged Lee to disperse his forces and to carry on the fight however possible. Lee responded that to allow that would be to let loose on the countryside an undisciplined mob of soldiers who would rob and plunder to support themselves. Such actions would certainly bring retaliation from the enemy, and he could not allow such a state of affairs to develop. Later that morning, Lee received Grant’s note turning down the proposed meeting, yet the grim news from Gordon had left him little room to negotiate. Now with his forces pressed in on one another, there appeared to be no other option but to request explicitly a surrender conference, which Lee did in a final note.

While waiting for the expected 10:00 a.m. meeting with Grant, Lee informally polled some of his commanders for their opinions on the situation. Longstreet and William Mahone counseled surrender. E. Porter Alexander opposed that view and encouraged Lee to disperse his forces and to carry on the fight however possible. Lee responded that to allow that would be to let loose on the countryside an undisciplined mob of soldiers who would rob and plunder to support themselves. Such actions would certainly bring retaliation from the enemy, and he could not allow such a state of affairs to develop. Later that morning, Lee received Grant’s note turning down the proposed meeting, yet the grim news from Gordon had left him little room to negotiate. Now with his forces pressed in on one another, there appeared to be no other option but to request explicitly a surrender conference, which Lee did in a final note.

The response at Grant’s headquarters was subdued. Only a feeble cheer and some tears greeted the news that Lee would meet to discuss surrender, although Grant did declare that his migraine headache had miraculously disappeared. Further communications proposed that Lee and his staff should find a location; Grant would meet them where they indicated. White truce flags went out from both sides. As the news of the truce took time to disseminate, there was some disagreement whether particular units should surrender directly to one another or wait for orders. By the early afternoon of 9 April, much of the fighting had stopped in Virginia. It is estimated that at this time the Confederates had approximately 10,000 effective soldiers in the field; Union forces numbered more than 60,000.

The Surrender

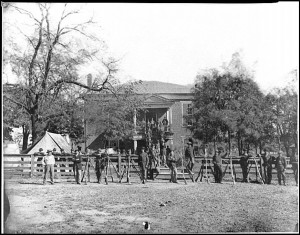

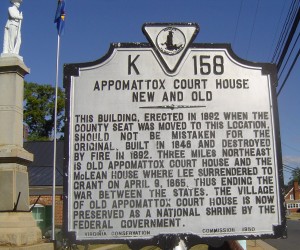

At midday, Lee and his aide Colonel Charles Marshall rode out on the road to Appomattox Court House. The first white civilian they encountered was local resident Wilmer McLean, who, when asked, initially offered a nearby outbuilding for the conference. When the shabby, unfurnished structure was declared unsuitable, McLean proffered his own, more comfortable home. What Marshall and Lee probably did not know is that McLean’s reluctance may have been a result of his earlier war experiences. By a remarkable coincidence, the McLean family had left a previous home after the house had served as a Confederate hospital and General P.G.T. Beauregard’s headquarters during First Bull Run, the first battle of the war in Virginia. Hoping to avoid the rest of the war, McLean had moved his family to Appomattox Court House in 1863.

A half-hour after Lee and Marshall arrived, Grant and his staff arrived at the McLean house at approximately 2:00 p.m. By all accounts, the contrast between the two commanders was extraordinary. Lee presented a dignified figure, tall and dressed in his best uniform, with a fine sword. In comparison, Grant was muddy from his long ride, wearing a simple soldier’s coat with only three-star shoulder straps to indicate his rank, and was swordless. While only Marshall accompanied Lee, Grant had a small entourage of staff and officers. These included Sheridan and Ord, as well as J.A. Rawlins, Rufus Ingalls, M.R. Morgan, Robert T. Lincoln (the president’s son), Adam Badeau, Orville Babcock, Horace Porter, Seth Williams, Theodore Bowers, and Ely Parker. There is some debate about other Federal officers and journalists who may or may not have been in the parlor during the conference.

A half-hour after Lee and Marshall arrived, Grant and his staff arrived at the McLean house at approximately 2:00 p.m. By all accounts, the contrast between the two commanders was extraordinary. Lee presented a dignified figure, tall and dressed in his best uniform, with a fine sword. In comparison, Grant was muddy from his long ride, wearing a simple soldier’s coat with only three-star shoulder straps to indicate his rank, and was swordless. While only Marshall accompanied Lee, Grant had a small entourage of staff and officers. These included Sheridan and Ord, as well as J.A. Rawlins, Rufus Ingalls, M.R. Morgan, Robert T. Lincoln (the president’s son), Adam Badeau, Orville Babcock, Horace Porter, Seth Williams, Theodore Bowers, and Ely Parker. There is some debate about other Federal officers and journalists who may or may not have been in the parlor during the conference.

After brief conversation about their mutual service in Mexico, Lee called Grant’s attention to the matter at hand by requesting his terms for surrender. Grant replied that they were as he had stated earlier: men and officers who surrendered were to be paroled and could not take up arms again until properly exchanged. Their arms and supplies were to be turned over as captured property. Lee asked Grant to write out the terms. In the written proposal, Grant added that officers would not have to surrender their side arms and may also keep their horses. Grant also stated that soldiers could go home and would not be disturbed by U.S. authority as long as they maintained their parole.

With this last condition, Grant exceeded his charter of negotiating only the surrender of the army. He effectively said that Confederate soldiers would not be treated as traitors by the U.S. government. Although Lincoln would probably have endorsed this decision, it was not Grant’s to make.

Lee commented that the terms would have a most happy effect on his army, but noted that in the Confederate army all cavalry and artillery horses were privately owned (as opposed to the army-owned Federal horses); did the terms mean that only officers could keep their horses? Grant considered, and he agreed that, as horses would be necessary in the coming months to the many small farmers in the ranks, they could be retained by all who claimed ownership. Marshall drafted a note of agreement, which Lee signed. Copies of the surrender terms and agreement were made, signed, and distributed. Marshall commented afterward: “There was no theatrical display about it. It was in itself perhaps the greatest tragedy that ever occurred in the history of the world, but it was the simplest, plainest, and most thoroughly devoid of any attempt at effect, that you can imagine.”

After the signing, the meeting began to dissolve into individual conversations between the officers present. Lee and Grant discussed the return of Federal prisoners, and the provision of rations by the well-supplied Federal army to the starving Confederate forces. There was no discussion of Lee’s surrendering his sword, despite the popular myth to the contrary. Lee met the other officers in the room, shaking hands with each before leaving the McLean house at approximately 3:00 p.m. Lee’s ride back to his camp through Confederate lines brought throngs of soldiers to the roadside, a few cheers, some tears, and much disbelief that the four years of intense combat had ended so abruptly.

After the signing, the meeting began to dissolve into individual conversations between the officers present. Lee and Grant discussed the return of Federal prisoners, and the provision of rations by the well-supplied Federal army to the starving Confederate forces. There was no discussion of Lee’s surrendering his sword, despite the popular myth to the contrary. Lee met the other officers in the room, shaking hands with each before leaving the McLean house at approximately 3:00 p.m. Lee’s ride back to his camp through Confederate lines brought throngs of soldiers to the roadside, a few cheers, some tears, and much disbelief that the four years of intense combat had ended so abruptly.

After Grant left the McLean house, Federal officers descended upon it, buying and taking the furniture as souvenirs. McLean tried to prevent the chaos, but his parlor was left a shambles. Grant cabled the news to Washington at 4:30 p.m. As word of the surrender spread through Federal lines, great rejoicing commenced, culminating in the firing of artillery salutes. Grant, sensitive to the proximity of his vanquished foe, quickly ordered the excessive exultation stopped.

The formal surrender ceremony took place on 12 April. General Joshua Chamberlain was given the honor of receiving the surrender, in this final encounter between the two armies. As the Confederate soldiers marched between the two liens of Federal soldiers, Chamberlain ordered his troops to display a carry arms salute. Confederate general John Gordon responded with an order in kind - “honor answering honor.” Confederate arms were stacked, banners laid on the ground, and the Southern soldiers began to go home. Approximately 28,000 Confederate soldiers surrendered at Appomattox. This number is higher than the effective number in the field at the truce because of the return of stragglers and deserters int he days between the cessation of hostilities and the surrender ceremony.

The surrender that took place at Appomattox Court House is remarkable for its lack of rancor between the two previously bitter enemies and for the dignity of the proceedings. Upon the appearance of flags of truce on the morning of the 9th, Confederate and Federal officers met between the lines to exchange greetings, information, and flasks. After the surrender, Federal soldiers freely shared the contents of their haversacks with their hungry Confederate counterparts. The surrender ceremony was marked by a profound respect on both sides. The choices made by the commanders of the two armies reflected an awareness of the long-term effects of the war on the nation. Grant could have treated the defeated Confederates far more harshly and deprived them of the basic necessities for starting their civilian lives again. Lee could have allowed his army to become a guerrilla fighting force, a decision that would have further embittered the two sides. Both commanders strove to set examples for their armies and their country to follow.

Other forces remained in the field, and it would be another year before Andrew Johnson could proclaim the insurrection at an end. Nonetheless, the end of the war in Virginia signaled the beginning of the end of the Confederate States of America.

- Lisa Lauterbach Laskin

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 67-72.]

Additional resources:

National Park Service - Appomattox Court House National Historic Park

Civil War Trust - Appomattox Court House

Civil War Trust - Grant and Lee Surrender Correspondence

Michael Haskew - Appomattox: The Last Day’s of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia