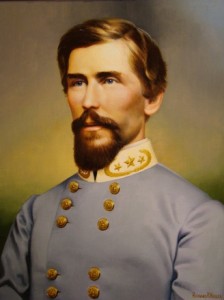

One of the more interesting and tragic figures of the Civil War, Pat Cleburne earned a fame that derived from four circumstances: his Irish birth, his remarkable effectiveness as a division commander in the Army of Tennessee, his proposal in January 1864 that the South free its slaves and incorporate them into the Confederate army, and his dramatic death in the ill-fated charge at Franklin, Tennessee, on 30 November 1864.

Cleburne was born on 16 March 1828 near Ballincollig in County Cork, Ireland. His father was a Protestant country physician and his mother was the daughter of a prominent Irish Protestant family. His mother died when he was only 19 months old, but not long afterward his tutor became his stepmother and the woman he called “Mamma” all his life. From age twelve to fifteen, Cleburne attended the private Greenfield School, but after his father died in 1843, the family could no longer afford the school fees and he took a job as an apothecary’s assistant in Mallow. Later he traveled to Dublin to seek admission to the Apothecaries College. Rejected, he joined the British army.

Cleburne spent two and one-half years in Her Majesty’s 41st Regiment. It was an unhappy duty. Instead of journeying to exotic far away places, the regiment was assigned to constabulary duty to keep the peace in an Ireland ravaged by the potato famine. At age twenty-one, Cleburne inherited a small legacy from his father’s estate and he used it to buy his way out of the army. He and his siblings then took passage to the United States and arrived in New Orleans on Christmas Day 1849.

The Cleburne siblings scattered to various parts of America. After a brief sojourn in Cincinnati, Cleburne settled in Helena, Arkansas, where he managed a drug store and later became a lawyer. When Arkansas seceded and war appeared imminent, Cleburne joined the local militia company and was elected its captain. When, after the outbreak of war, that company was amalgamated with nine others to form a regiment, Cleburne was elected its colonel, and when that regiment was brigaded together with three others under the overall command of the professional soldier William J. Hardee, that officer recommended Cleburne for command of the brigade.

Cleburne saw his first important action in the battle of Shiloh on 6-7 April 1862. His brigade was in the front rank during the surprise morning attack on 6 April. Despite horrific casualties, he pressed his command forward until nightfall, when his remaining troops bivouacked on the battlefield. The next morning, Ulysses S. Grant’s counterattack forced Cleburne’s brigade back along with the rest of the army to its starting point. Of the 2,750 men in his six regiments, 1,043 were killed, wounded, or missing – losses of 38 percent. Cleburne’s leadership in this, his first battle, was marked more by enthusiasm than judgment, but he absorbed several valuable lessons that he subsequently applied in other battles. In particular, these included using artillery with the advance and developing a specialized group of sharpshooters.

During the Confederate invasion of Kentucky in late summer, Cleburne commanded a small division consisting of his own brigade plus that of Preston Smith. His division led the advance northward from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Richmond, Kentucky, where Cleburne’s small division played the central role in defeating and pursuing a disorganized Federal division on 29-30 August 1862. While preparing the attack, Cleburne was wounded in the face. A minie ball pierced his left cheek, smashed several teeth, and exited through his mouth. He recovered in time to participate on 8 October 1862 in the battle of Perryville, where again his command broke the enemy line, though this time the Federals did not abandon the battlefield. In both of these fights, Cleburne demonstrated his ability to apply practical lessons of combat by making effective use of both artillery and sharpshooters.

Promoted to major general and the permanent command of a division in November, Cleburne embarked on a series of remarkable battlefield performances. In the battle of Stones River (or Murfreesboro) on 31 December 1862 – 2 January 1863, his division routed the Union right wing and drove it four miles back onto the Nashville Pike. In the battle of Chickamauga on 19-20 September 1863, his division assailed with such ferocity an entrenched force significantly stronger than his own that the Federal commander, William S. Rosecrans, pulled forces from other parts of the field to reinforce the position on Cleburne’s front. That opened the way for the successful Confederate counterattack that won the day.

Cleburne’s military prowess was most evident in the battles for Chattanooga. On the north end of Missionary Ridge on 25 November 1863, Cleburne’s single reinforced division hurled back repeated attacks by William T. Sherman’s four divisions in what was supposed to be the major Federal effort that day. Failing to move Cleburne off Tunnel Hill, Sherman asked Grant for support, and Grant authorized a feint by George Thomas’s corps in what became the charge up Missionary Ridge. After the rest of the Confederate army broke, Cleburne was assigned the task of defending the rear guard, including the army’s wagon trains. In that role, Cleburne’s division beat off a concerted attack by Joseph Hooker’s Corps at Ringgold Gap on 27 November 1863. Twice in three days, therefore, Cleburne’s division saved the Army of Tennessee from destruction.

Though Cleburne’s own prestige was at an all time high in the winter of 1863-1864, the Confederacy itself faced a bleak future. In an effort to solve the Confederacy’s desperate problem of personnel shortages, Cleburne in January 1864 asked for a meeting of the army’s senior officers. At that meeting he formally proposed that the Confederacy abolish slavery and recruit black troops for the Confederate army. He argued that, along with generating a potential half million new soldiers, such a step would pave the way for recognition by Britain and France and strip the Lincoln administration of a moral issue. The horrified reaction of most of those present showed him that this was an issue whose time had not yet come, and all present were ordered to keep the proposal a secret.

Cleburne remained an active and effective division commander in the campaign for Atlanta during May-July 1864, winning important tactical victories at Kennesaw Mountain on 27 June and the battle of Atlanta (or Bald Hill) on 22 July. In the battle of Jonesboro on 31 August – 1 September 1864, he commanded a corps in battle for the only time in the war. None of those battles was a clear Confederate victory, however, and on 1 September 1864 John Bell Hood was forced to evacuate Atlanta.

Cleburne’s division took the lead again during Hood’s desperate invasion of Tennessee in the fall of 1864. Hood held him partly responsible for the “escape” of the enemy at Spring Hill on 29 November 1864, and both Hood and Cleburne may have conceived of the charge at Franklin the next day to be an opportunity for Cleburne to atone. In that attack, Cleburne’s division held the position of dubious honor in the center of the Confederate line as it swept forward across two and one-half miles of open ground against well-prepared entrenchments. About fifty yards from the Federal line, Cleburne fell with a bullet in his chest, one of six Confederate generals to die in that assault.

- Craig L. Symonds

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 455-457.]

Cleburne is buried at the Confederate Cemetery in Helena, Arkansas according to the website Find A Grave.

Symonds, Craig L. Stonewall of the West: Patrick Cleburne and the Civil War.

Gillum, Jamie. Major General Patrick R. Cleburne’s Last Days in Life and Death: Contemporary Accounts of Cleburne and his Division. (The 1864 Tennessee Campaign) (Volume 2)

U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Patrick R. Cleburne and the Tactical Employment of His Division at Chickamauga.