Lieutenant General John Bell Hood stood on the high slope of Winstead Hill, just south of Franklin, Tennessee, on the afternoon of 30 November 1864. Hood appeared older than his thirty-three years, as he leaned on a crutch supporting the stump of an amputated leg, while a useless arm hung by his side, the results of wounds at Chickamauga and Gettysburg, respectively. He stood on the approximate site of present-day battlefield map, holding a pair of field glasses to his eyes as he surveyed the Federal line on the southern edge of the little town. Immediately to the front and below Hood, two corps of the Confederate Army of Tennessee were assembled. The general was deciding whether to attack the Union position, where artillery bristled through strong earthworks fronted by abates. Cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest, infantry corps commander General Benjamin F. Cheatham, and probably others, had advised him not to make a frontal assault. But the young general did not accept their advice. Returning the field glasses to a leather case, Hood announced something to the effect that the army would make the fight.

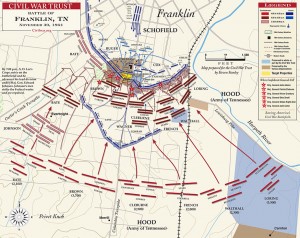

Shortly after 4:00 P.M., on that Indian summer day, the Confederates moved forward, bands playing and regimental flags waving, as they marched across the bluegrass fields toward Franklin, where the Yankee troops waited in their formidable entrenchments. For the attackers the battle would be a terrible defeat – in some ways the worst fight in which the Army of Tennessee was ever engaged. Of a total force of about 23,000, there were 1,750 Southern troops killed. Another 5,500 men were wounded or captured. Six generals were killed, five wounded and one captured. Of 100 Confederate regimental commanders, more than 60 were killed or wounded. The Federals, with more than 15,000 engaged, suffered approximately 2,500 casualties, with about 200 of those killed. Clearly, General Hood had made an awful mistake in launching a frontal assault at Franklin.

The background for the Franklin campaign began with the conclusion of the Atlanta campaign. After the Confederate evacuation of Atlanta, Hood hoped to draw General William T. Sherman away from that city by attacking his railroad supply line in north Georgia. Sherman sent some forces to give chase, briefly, but then stopped, complaining that Hood could twist and turn until his army would be worn out in pursuit. Besides, Sherman had something else in mind. He “would infinitely prefer to…move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea.” For such a march, Sherman did not need a railroad, nor a base. His men would take what they needed from the countryside. In his own words: “I can make that march and make Georgia howl!”

The background for the Franklin campaign began with the conclusion of the Atlanta campaign. After the Confederate evacuation of Atlanta, Hood hoped to draw General William T. Sherman away from that city by attacking his railroad supply line in north Georgia. Sherman sent some forces to give chase, briefly, but then stopped, complaining that Hood could twist and turn until his army would be worn out in pursuit. Besides, Sherman had something else in mind. He “would infinitely prefer to…move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea.” For such a march, Sherman did not need a railroad, nor a base. His men would take what they needed from the countryside. In his own words: “I can make that march and make Georgia howl!”

Meanwhile, General Hood moved into north Alabama. He planned to march his army into middle Tennessee, capture Nashville, and continue north into Kentucky, maybe even Ohio, or turn east to join forces with Robert E. Lee. Hood believed that Sherman would be compelled to come after him. It was not to be. By mid-November, Sherman was moving toward Savannah and Hood toward Nashville. Sherman, ironically, thought that Hood would probably follow him. If not, General George H. Thomas must shoulder the responsibility of dealing with Hood and the Army of Tennessee.

Thomas was then at Nashville in command of the Department of the Cumberland. While he was in overall charge of the Federal troops that would be massing in Tennessee’s capital to stop Hood, the actual field commander of forces deployed south of Nashville to delay Hood’s advance was John M. Schofield. Schofield had been a classmate of Hood’s at West Point. He had been detached by Sherman to help Thomas defend against Hood, and he commanded the IV and XXIII Army Corps, along with a small contingent of cavalry.

Thomas was then at Nashville in command of the Department of the Cumberland. While he was in overall charge of the Federal troops that would be massing in Tennessee’s capital to stop Hood, the actual field commander of forces deployed south of Nashville to delay Hood’s advance was John M. Schofield. Schofield had been a classmate of Hood’s at West Point. He had been detached by Sherman to help Thomas defend against Hood, and he commanded the IV and XXIII Army Corps, along with a small contingent of cavalry.

A Confederate flanking march almost cut Schofield off at the Duck River. Hood came even closer at Spring Hill on the afternoon of 29 November, but somehow failed – a failure never fully explained – to block the road north to Franklin. Thus Schofield’s forces marched through the little town during the night. By the morning of 30 November, the Federals were in Franklin, where they occupied and strengthened the earthworks that had been prepared more than a year before. By noon the Union position was formidable.

Hood was enraged when he learned that the Federals had marched by him during the night. Proceeding to blame nearly everyone except himself, he then put the Confederates in motion toward Franklin. Somehow, by afternoon, Hood had convinced himself that for purposes of discipline and restoration of élan what the army needed was to make a frontal assault. Yet he did not do the things that might have enabled a frontal assault to succeed.

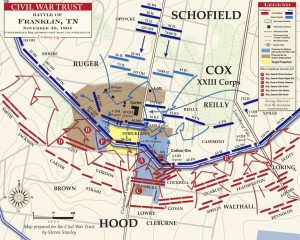

When Hood gave the signal for the advance, most of Stephen D. Lee’s corps was not present, but still on the march south of Franklin. Also, most of the army’s artillery was not up, but in the process of being brought forward with Lee’s Corps. Thus Hood would assail the Franklin works with only two of his three corps, and artillery support would be virtually nonexistent. Worst of all, Hood did not position his troops properly for a successful attack. His hope for smashing the Federal center along the Columbia-Franklin Pike depended upon two divisions, one advancing on each side of the pike. Together, the two divisions possessed only seven brigades of the total of eighteen infantry brigades that Hood had on the field. His forces were not properly massed to achieve their objective.

The Confederate attack was in near perfect alignment, an unforgettable martial display, according to numerous witnesses. It was the last grand charge of the war. The rebel leading units overwhelmed the Federals who were stationed about a third of a mile in front of their main line and chased them into the works along the Columbia-Franklin Pike. The Confederates charged through the yard of the Carter House (still extant) only to be met by the countercharging brigade of Colonel Emerson Opdycke. Other Federals quickly rallied to drive back the Confederates and close the penetration in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. The Southerners hung on at the outer ditch of the main earthworks, only to find, some of them, that they were subjected to enfilading fire. The reels at different points along the line made numerous separate charges until about 10 P.M., when the sounds of guns gradually died away.

In the outer ditch, Confederate dead and dying laid five or six deep in some places. Wounded soldiers of both sides suffered further as the temperature dropped through the night. During the night, General Schofield, as he had intended all along, pulled his army out and headed for Nashville. The Confederates advanced to Nashville the next day, but the Army of Tennessee never recovered from the battle of Franklin.

— James L. McDonough

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 771-772.]

Among the dead were six Confederate generals including Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, who is considered to be the “Stonewall of the West.”

For further information:

Civil War Trust’s Battle of Franklin page.

Battle of Franklin Trust website.

Jacobson, Eric A., For Cause & for Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill & the Battle of Franklin.

Jacobson, Eric A., Baptism of Fire.

Eric Jacobson’s books are also available at the Battle of Franklin Trust’s web bookstore, with proceeds benefiting the Trust.