Fort Pillow was located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, 40 miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. Constructed by Confederate General Gideon Pillow in 1861, it overlooked the river, and its principal function was to control river traffic on the Mississippi. On 12 April 1864, the fort became the site of one of the most controversial events of the American Civil War: the Fort Pillow massacre.

Fort Pillow was located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, 40 miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. Constructed by Confederate General Gideon Pillow in 1861, it overlooked the river, and its principal function was to control river traffic on the Mississippi. On 12 April 1864, the fort became the site of one of the most controversial events of the American Civil War: the Fort Pillow massacre.

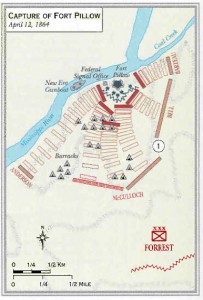

The fort consisted of a dirt parapet, approximately 6 to 8 feet high, and formed a 125-foot semicircle. Built on a steep bluff that descended rapidly to the Mississippi, the fort faced east. To the north, a small stream, Cool Creek, entered the river. To the south, a small town consisting of storage buildings and bunkhouses sat in a ravine below the fort.

The fort was protected by three semicircular lines of defense. The outer line spanned about two miles and ran from the small town to the south of the fortress to Coal Creek on the other side of the fort. The second line was approximately 600 yards inside the outer lines. The final line was the fort itself. The terrain around the fort was hilly with numerous ravines. The fort was manned by 580 Union soldiers; 285 belonged to the 13th Tennessee Cavalry, while 292 were African-American soldiers who were part of either the 6th U.S. Heavy Artillery or the 6th U.S. Colored Light Artillery. Major Lionel F. Booth commanded the fort, with Major William F. Bradford second in command.

The fort was protected by three semicircular lines of defense. The outer line spanned about two miles and ran from the small town to the south of the fortress to Coal Creek on the other side of the fort. The second line was approximately 600 yards inside the outer lines. The final line was the fort itself. The terrain around the fort was hilly with numerous ravines. The fort was manned by 580 Union soldiers; 285 belonged to the 13th Tennessee Cavalry, while 292 were African-American soldiers who were part of either the 6th U.S. Heavy Artillery or the 6th U.S. Colored Light Artillery. Major Lionel F. Booth commanded the fort, with Major William F. Bradford second in command.

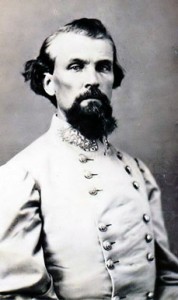

On the morning of 12 April, Confederate troops under Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who had been conducting raids throughout western Kentucky and Tennessee, surrounded the garrison on three sides. The Confederates had quickly seized the small town south of the fort and a ravine north of it. After waiting for his ammunition to be replenished, Forrest sent out a flag of truce at 3:30 that afternoon and demanded the garrison’s immediate surrender. He told the Federals that if they surrendered, they would be treated as prisoners of war, but, if they refused, they would be shown no quarter. Major Booth had been killed by sniper fire, so the decision fell to Major Bradford, who asked Forrest for 1 hour to deliberate. Suspecting that the Federals were stalling to procure the assistance of a Union gunboat (the New Era) on the Mississippi, Forrest gave Bradford 20 minutes to decide.

When Union forces refused to surrender, Forrest launched a vigorous assault on the fort. With good position and superior numbers, the Confederates quickly overwhelmed the Union forces. What made the assault on Fort Pillow infamous, however, was the manner in which it was conducted. As Confederate soldiers gained the parapet, panic seized Union soldiers, who hastily retreated down the bluff. Many Union soldiers jumped into the Mississippi River, hoping to swim to the New Era. Other Union soldiers laid down their weapons and attempted to surrender. Confederate troops, however, did not acknowledge surrender and subjected the garrison to a merciless fire of bullets. Many Union soldiers were gunned down after they had thrown away their weapons. Black soldiers were the especial target of Confederate wrath. Not only did the Confederate government refuse to recognize African-Americans as bona fide soldiers, the average Confederate soldier was particularly threatened by the sight of former slaves wearing Union blue. Cries of “No quarter” and “kill the damned niggers” punctuated the confusion. Countless accounts told of black soldiers gunned down or bayoneted in the most brutal fashion.

When Forrest finally gained control of the situation and ordered his forces to cease firing, close to 50 percent of the Federal troops had perished. The death rate for black troops, however, was significantly higher than for white soldiers (64 percent compared with 31 percent). In addition to high casualties, stories of all sorts of atrocities quickly spread throughout the North. These included such gruesome acts as live burials, the killing of women and children who were in the town south of the fort, and wounded soldiers being set on fire.

National Park Service historian emeritus Ed Bearss discusses the battle and massacre at Fort Pillow.

Northern public opinion was outraged, and in a public speech shortly after the massacre, President Lincoln threatened retaliation if the allegations were proved true. In Congress, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was directed to investigate the Fort Pillow massacre. After interviewing dozens of witnesses, the committee published a report in early May that charged that the Confederates were indeed guilty of many of the reported atrocities.

While the Lincoln administration threatened retaliation and discussed various options in cabinet meetings, nothing came of such threats. In the end, the administration realized that Richmond authorities would never recognize African-American soldiers as legitimate, and to avenge Fort Pillow would result in a cycle of meaningless reprisals.

Although reports of the massacre were not without exaggeration, particularly the accounts of live burials and the slaughter of women and children, most historians believe that soldiers, particularly African-Americans, were needlessly butchered. While historians sympathetic to Forrest argue that there was no “official” surrender of the garrison, there can be little doubt that many soldiers tried to surrender and were killed after they had thrown down their weapons. While Forrest may not have explicitly ordered the massacre, given the well-known attitude of Confederate soldiers toward African-American soldiers, Forrest understood what the outcome of an attack would be. Indeed, for numerous African-American soldiers, Fort Pillow became the rallying cry. There are numerous accounts of black troops going into battle crying “Fort Pillow.” Instead of unnerving black soldiers, as the Confederates had intended, the massacre at Fort Pillow had the opposite result.

- Bruce Tap

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 746-748]

Union and Confederate casualties from the Fort Pillow Massacre can be found here.

Additional resources:

River Run Red: The Fort Pillow Massacre in the Civil War by Andrew Ward

Fort Pillow, a Civil War Massacre, and Public Memory by John Cimprich

The River Was Dyed with Blood: Nathan Bedford Forrest and Fort Pillow by Brian Steel Wills