Pleasant Hill was the last major battle of the Red River campaign of 1864. Persistent if not talented, Union Major General Nathaniel P. Banks still held onto his scheme to take Shreveport, Louisiana, despite his loss to Confederate Major General Richard Taylor at Mansfield on 8 April. By rejoining his Red River Expeditionary Force with Admiral David D. Porter’s gunboat fleet and Brigadier General Thomas Kilby Smith’s detachment of XVII Corps at the Red River, he believed he could salvage his expedition. Under cover of darkness during the night of 8-9 April, Banks evacuated his rear guard positions for Pleasant Hill, some fourteen miles to his rear. To mask his withdrawal, two divisions under Brigadier Generals W.H. Emory and J.A. Mower remained behind.

Although significantly outnumbered, the aggressive Taylor pressed his pursuit in expectation of destroying Banks’s forces. At dawn Taylor, accompanying Major General Thomas Green’s cavalry, led two brigades of Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill’s division under Mosby M. Parsons and James C. Tappan in pursuit of the Federals’ rear guard. Having suffered heavy losses the day before at Mansfield, Major General John G. Walker’s and Brigadier General Camille de Polignac’s Divisions brought up the Confederate rear.

Arriving at Pleasant Hill’s outskirts at about 9 A.M., Taylor was somewhat surprised to find the Federals forming a line of battle. As Taylor waited for Churchill’s Division to come up, reconnaissance forays by Brigadier General Hamilton P. Bee’s cavalry confirmed that Banks’s troops were indeed occupying formidable defensive positions. Attackers would be forced to cross an open field in the face of fire from skirmishers concealed in a ravine that, in turn, fronted a low plateau on which Banks had placed his artillery and main infantry positions. Still, Taylor remained firmly convinced that he could exploit the momentum from the morale advantage he had gained from his success at Mansfield.

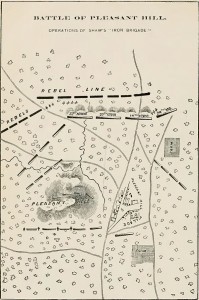

Taylor’s troops, however, were exhausted. Polignac and Walker’s men had fought a pitched battle the previous day and Churchill’s had marched forty-five miles in thirty-six hours. Reluctantly, Taylor was forced to allow his troops, now reinforced to some 13,500 men, two hours’ rest before opening his attack. At 3 P.M., disregarding his opponent’s superior position and numbers, Taylor set his attack in motion. Pinning his strategy on Churchill’s relatively fresh troops, he ordered his two divisions southward in a flanking maneuver. Within an hour and a half, Churchill’s force, led by Tappan and Parsons, stood in line of battle across the Sabine Road. Taylor’s plan called for Churchill’s troops to launch a decisive attack on the Union southern flank, rolling it upon itself. As the enemy line collapsed, Walker was then to throw his division at Banks’s center while Bee’s Texas Cavalry was to exploit any breakthrough with a mounted saber attack. Polignac’s survivors, who had borne the worst of the fighting at Mansfield, were to rest as reserves on the Confederate far left.

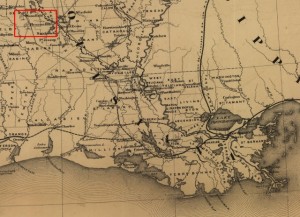

Map from the book “History of Iowa” showing the positions of Iowa regiments during the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

Confederate attack opened at 4:30 P.M. as Taylor’s artillery commander, Major Joseph Brent, ordered his gunners to pull their lanyards and the infantry stepped off into a hail of Union fire. Parsons and Tappan achieved initial success on the Confederate right as they overwhelmed the brigade of Colonel Lewis Benedict who was killed in the fighting. Taylor saw less success on his left as Union troops repulsed savage assaults by Walker’s infantry and Bee’s ill-fated cavalry charge. After over an hour of desperate and costly fighting, Churchill’s command under Parsons and Tappan was making headway on the Confederate right but the Confederate assaults on the Union center had made little progress. As Walker’s brigade commanders struggled to maintain their momentum, Taylor ordered up Polignac’s Division. Polignac formed his line between General Thomas Green’s now dismounted cavalry under Brigadier General James Major and Walker’s left brigade under Colonel Horace Randal. Meeting Polignac’s, Walker’s and Green’s combined onslaught, Colonel William T. Shaw’s 2nd Brigade of Brigadier General A.J. Smith’s XVI Corps 3rd Division, which had broken every assault Taylor had thrown against them, finally was exhausted and grudgingly gave way in the center. At the same time, the Federal left collapsed under pressure from Churchill’s two brigades. Churchill’s advantage, however, was short-lived. Just as he sensed victory, a determined counterattack by veteran regiments of A.J. Smith’s XVI Corps emerged from the woods to slam into Parson’s right flank. As Parson’s troops gave way, the momentum shifted to the Federals as Mower led the Union center forward. The Federal counterattack crushed Taylor’s critical flanking movement and with it hopes of adding a second victory to Mansfield. Although Taylor continued to press the Union center, fatigue, disorganization and the approaching nightfall soon dictated the battle’s end.

Despite having won a tactical victory at Pleasant Hill, a demoralized Banks withdrew under cover of night to Grand Ecore and eventually on to Alexandria. Taylor, although disappointed in not having destroyed Banks, contented himself with having finally driven the Federals from western Louisiana. Both sides had suffered heavily during the two days’ fighting. Federal records added 152 killed, 859 wounded and 495 captured at Pleasant Hill to the losses of the previous day at Mansfield. Taylor estimated his total losses at 2,200.

- Jeff Kinard

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1528-1529]

Battle of Pleasant Hill Reenactment Website

Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War (contains a chapter dedicated to the Battle of Pleasant Hill and the 32nd Iowa Infantry’s role in the engagement)