Also known as the battle of Sabine Crossroads, this clash was the decisive battle in northwestern Louisiana that effectively halted the Union’s Red River campaign of 1864. In early 1864, Federal commanders devised the invasion of Texas by way of the Red River in Louisiana. Major General Nathaniel Banks assumed command of the Red River Expeditionary Force and by late March had taken the strategic town of Alexandria in central Louisiana. Banks next planned to push up the Red River to Shreveport, headquarters of the Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, General Edmund Kirby Smith. There he planned to link up with a force under Major General Frederick Steele for the final drive into Texas.

Rather than risk a disastrous defeat, Smith, with fewer than 10,000 available troops under Major General Richard Taylor, ordered Taylor to fall back toward Shreveport. As a reluctant Taylor grudgingly marched his small force northward toward the village of Mansfield, Banks made a fateful decision. Two roads led north to Shreveport. The longer hugged the riverbank, thus offering his troops the protection of the guns of Admiral David D. Porter’s gunboat fleet steaming up the river. Banks, however, eager to reach Shreveport as quickly as possible, chose the more direct overland route. Although the road passed through Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, occupied by Taylor’s main force, Banks evidenced little concern, convinced that the Confederates were unwilling to fight. On 6 April the Federal army abandoned the protection of the river to march through the “howling wilderness” of northwestern Louisiana.

Rather than risk a disastrous defeat, Smith, with fewer than 10,000 available troops under Major General Richard Taylor, ordered Taylor to fall back toward Shreveport. As a reluctant Taylor grudgingly marched his small force northward toward the village of Mansfield, Banks made a fateful decision. Two roads led north to Shreveport. The longer hugged the riverbank, thus offering his troops the protection of the guns of Admiral David D. Porter’s gunboat fleet steaming up the river. Banks, however, eager to reach Shreveport as quickly as possible, chose the more direct overland route. Although the road passed through Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, occupied by Taylor’s main force, Banks evidenced little concern, convinced that the Confederates were unwilling to fight. On 6 April the Federal army abandoned the protection of the river to march through the “howling wilderness” of northwestern Louisiana.

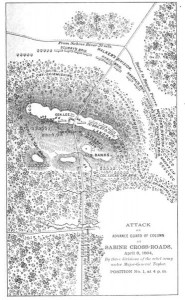

Taylor soon decided to ignore Smith’s orders and confront Banks near Mansfield, a small village south of Shreveport. During the early morning hours of 8 April, Taylor formed his 5,300 infantry into a line at Sabine Crossroads, a strategic intersection three miles southeast of Mansfield. Partially concealed in the edge of a pine forest, Brigadier General James T. Major’s dismounted cavalry anchored the left of the line next to Brigadier General Alfred Mouton’s division as Major General John G. Walker’s Texas Division formed on the right. Twelve artillery batteries and 3,000 cavalry brought Taylor’s strength to about 8,800.

Taylor soon decided to ignore Smith’s orders and confront Banks near Mansfield, a small village south of Shreveport. During the early morning hours of 8 April, Taylor formed his 5,300 infantry into a line at Sabine Crossroads, a strategic intersection three miles southeast of Mansfield. Partially concealed in the edge of a pine forest, Brigadier General James T. Major’s dismounted cavalry anchored the left of the line next to Brigadier General Alfred Mouton’s division as Major General John G. Walker’s Texas Division formed on the right. Twelve artillery batteries and 3,000 cavalry brought Taylor’s strength to about 8,800.

Ignoring warnings from his cavalry commander, Brigadier General Albert L. Lee, Banks continued to Sabine Crossroads. Although the Federals numbered nearly 18,000, their deployment was dictated by the narrow road, barely wide enough for a single wagon. Lee was particularly concerned over the placement of the supply trains. His own, numbering three hundred wagons, stretched three miles to the rear and blocked both retreat and reinforcements. Still, Lee continued his advance and, pushing back Confederate skirmishers, reached Honeycutt Hill, a low wooded ridge, late in the morning. Supported by two infantry brigades, Lee’s forces numbered some 4,800 men.

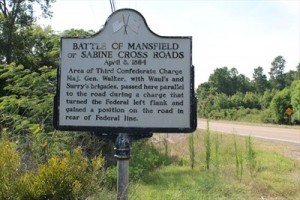

By noon Union and Confederate troops faced one another across a broad field from positions along opposing tree lines. As more Union troops and artillery arrived, the afternoon began to unfold into a series of probing cavalry actions interspersed by artillery duels. Shortly after 4 p.m. an impatient Taylor finally ordered his men forward. Crossing the field under a “murderous fire of artillery and musketry” Mouton’s and Walker’s Divisions crashed into the Federal positions, which soon crumbled in the ensuing hand-to-hand fighting. Mouton was killed in the assault and command of his division passed to the commander of his Texas Brigade, the French-born Brigadier General Camille de Polignac. As Polignac and Walker continued their attack, the Union resistance collapsed and soon deteriorated into a route with Confederate troops enveloping both flanks. Panicked troops poured to the rear along the already wagon-jammed road, abandoning their transports to the advancing Confederates.

By noon Union and Confederate troops faced one another across a broad field from positions along opposing tree lines. As more Union troops and artillery arrived, the afternoon began to unfold into a series of probing cavalry actions interspersed by artillery duels. Shortly after 4 p.m. an impatient Taylor finally ordered his men forward. Crossing the field under a “murderous fire of artillery and musketry” Mouton’s and Walker’s Divisions crashed into the Federal positions, which soon crumbled in the ensuing hand-to-hand fighting. Mouton was killed in the assault and command of his division passed to the commander of his Texas Brigade, the French-born Brigadier General Camille de Polignac. As Polignac and Walker continued their attack, the Union resistance collapsed and soon deteriorated into a route with Confederate troops enveloping both flanks. Panicked troops poured to the rear along the already wagon-jammed road, abandoning their transports to the advancing Confederates.

The timely arrival, however, of Brigadier General William H. Emory’s division some three miles to the rear of the initial battle saved Bank’s force from complete disaster. Shortly before dusk he expertly deployed his troops along Chapman Hill, a steep ridge fronted by an orchard known as Pleasant Grove. Despite repeated Confederate attacks, Emory held his position, thus protecting the remainder of the Federal train and the troops trapped by the narrow road.

Taylor was convinced he won a decisive victory. The action had cost Banks 113 killed, 581 wounded, and 1,541 missing - a total of 2,235 men. In addition, the Confederates captured hundreds of small arms, twenty artillery pieces, nearly 1,000 draft animals, and 250 wagons.

Taylor was convinced he won a decisive victory. The action had cost Banks 113 killed, 581 wounded, and 1,541 missing - a total of 2,235 men. In addition, the Confederates captured hundreds of small arms, twenty artillery pieces, nearly 1,000 draft animals, and 250 wagons.

Taylor’s losses were also heavy - approximately 1,500 of his original 8,800 men. Yet the battle of Mansfield had shaken Banks and convinced him to terminate his invasion plans and return to Alexandria. Although the Federals would win the battle the following day at Pleasant Hill, the Red River campaign had failed at Mansfield.

- Jeff Kinard

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1248-1249]

Resources:

Civil War Trust’s Battle of Mansfield page

Friends of Mansfield Battlefield

Dark and Bloody Ground: The Battle of Mansfield and the Forgotten Civil War in Louisiana

Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War