During the winter of 1862-1863, Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant made several unsuccessful forays to capture the strategic fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. A combination of swampy bogs along the Yazoo River north of the city, the 200-foot-high bluffs fringing the river west of the city, determined Confederate resistance, and rebel cavalry raids along his lines of communication thwarted Grant’s every attempt to seize the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy.”

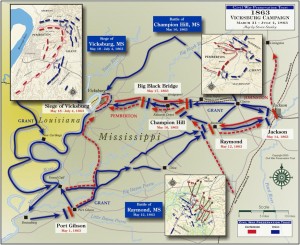

In March 1863, Grant proposed a bold stroke to circumvent Vicksburg’s natural obstacles and Confederate fortifications. He ordered his army to march south of Vicksburg on the west side of the Mississippi and sent Rear Admiral David D. Porter’s supporting flotilla past the citadel’s batteries to rendezvous with his forces south of Vicksburg. To disrupt rebel communications east of Vicksburg, he sent Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson’s 1,700 cavalrymen on a lengthy raid from La Grange to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, Confederate commander of Mississippi and Easatrn Louisiana, on the other hand, found himself bereft of cavalry, “deprived of his eyes” and a “blinded leader dangerously in the dark.” That situation had resulted because Lieutenant General Joseph E. Johnston had reassigned most of Pemberton’s cavalry to the Army of Tennessee, rendering Pemberton’s intelligence slow and ineffectual.

Consolidating at Hard Times, Louisiana, Grant prepared to launch Major General John McClernand’s XIII Corps and Major General James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps across the Mississippi. He had left Major General William T. Sherman’s XV Corps to demonstrate along the Yazoo to divert Pemberton’s attention from the Union crossing. When Grant discovered Confederate defenses at Grand Gulf, twenty-five miles south of Vicksburg, to be too imposing, he selected a landing site farther downriver. From 30 April to 1 May, Grant hurled 24,000 men across the Mississippi at undefended Bruinsburg in America’s largest amphibious operation up to that time.

Throughout 1 May, Brigadier General John S. Bowen furiously counterattacked with his 8,000 troops but failed to push the Union invaders back into the river. On 3 May, Grant dislodged the remaining defenders of Port Gibson, securing his beachhead and forcing Bowen to abandon Grand Gulf. Grant then continued his overland campaign to capture Vicksburg.

Throughout 1 May, Brigadier General John S. Bowen furiously counterattacked with his 8,000 troops but failed to push the Union invaders back into the river. On 3 May, Grant dislodged the remaining defenders of Port Gibson, securing his beachhead and forcing Bowen to abandon Grand Gulf. Grant then continued his overland campaign to capture Vicksburg.

Pemberton found himself in a dilemma. Johnston directed Pemberton to link up with him to defeat Grant in open battle. Convoluting the issue, President Jefferson Davis ordered Pemberton to “hold the city at all cost.” Pemberton followed his president’s instructions and his own inclination to defend the fortified city. Confederate indecision allowed Grant to proceed with his revised plan to cross the Big Black River and advance northeast to threaten both Jackson and Vicksburg.

Grant organized his 41,000 infantry into three columns. McClernand advanced on the left with instructions to hug the river. Sherman arrived at Grand Gulf with his corps to fill Grant’s center, while McPherson marched on the right.

On 12 May near Raymond, fourteen miles southwest of Jackson, Grant encountered the first major Confederate resistance. Brigadier General John Gregg advanced out of Jackson with his brigade and confronted McPherson’s advance guard, led by Major General John A. Logan. In a heated battle, Gregg’s 5,000 men held their line for six hours before superior numbers forced them to retreat. Reports listed Union losses as 66 killed, 339 wounded, and 37 missing, while Gregg reportedly lost 100 killed, 305 wounded, and 415 taken prisoner.

Grant seized an opportunity to drive a wedge between two Confederate forces and occupy Jackson He directed McPherson northeast to Clinton to destroy the railroad and then to move on to Jackson, while Sherman moved straight through Raymond toward the capital. McClernand’s orders included being in position to support the other two corps and guard against any attack by Pemberton from the west.

On the night of 13 May, as Grant made his dispositions, Johnston arrived in Jackson to take command of all Confederate forces in Mississippi. Piqued to discover Grant’s force between Jackson and Vicksburg, Johnston abandoned his initial plan for a consolidated attack against Grant. Union troops cut both the rail and telegraph lines, making any coordination between the separate Confederate armies slow and unreliable at best.

The same day that Gregg confronted the advancing Yankees at Raymond, Pemberton sallied out of Vicksburg with 18,500 men, crossed the Big Black River, and marched about halfway to Jackson. Advised of Pemberton’s actions, Johnston recognized an opportunity to strike Grant’s divided forces. He sent three couriers to convey his instructions to Pemberton to descend on the Federals’ rear at Clinton. In the meantime, on 14 May, with only 6,000 troops to defend the incomplete earthworks at Jackson, Johnston decided to abandon the city and reconsolidate near Calhoun. This action actually took Johnston farther from Pemberton. By the end of the 14th, Sherman’s troops had fought their way through the thin Confederate rear guard and occupied Jackson, capturing three artillery batteries and 200 prisoners in the process.

After a council of war with his subordinate commanders, Pemberton took their advice and chose not to join Johnston. Instead he would march southeast with his outnumbered force to cut Grant’s lines to the Mississippi. He remained unaware that Grant had departed Grand Gulf with all the ammunition his army could transport in confiscated wagons, carts, and fancy carriages. (Grant had, however, issued only five days’ rations for his troops, planning to forage freely from local farms and plantations. his men ate so much poultry during their march that the mere mention of chickens or turkeys spoiled their appetite.) With this shrewd maneuver, Grant negated Pemberton’s threat by intentionally cutting himself off from a long supply trail to the Mississippi.

After a council of war with his subordinate commanders, Pemberton took their advice and chose not to join Johnston. Instead he would march southeast with his outnumbered force to cut Grant’s lines to the Mississippi. He remained unaware that Grant had departed Grand Gulf with all the ammunition his army could transport in confiscated wagons, carts, and fancy carriages. (Grant had, however, issued only five days’ rations for his troops, planning to forage freely from local farms and plantations. his men ate so much poultry during their march that the mere mention of chickens or turkeys spoiled their appetite.) With this shrewd maneuver, Grant negated Pemberton’s threat by intentionally cutting himself off from a long supply trail to the Mississippi.

When Johnston learned of Pemberton’s plans he hurriedly sent additional dispatches urging Pemberton’s compliance with his initial guidance to consolidate their forces. By then it was too late. One of Johnston’s original couriers, secretly a Northern sympathizer, informed Grant of Johnston’s plans, and on 16 May the Union commander thrust most of his army westward from Jackson to engage Pemberton. Grant left Sherman in Jackson with orders to destroy anything of military value within the city. Sherman’s men reacted with alacrity, ransacking and burning much of the city before departing.

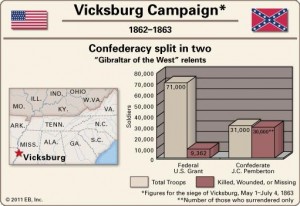

On 16 May, eighteen miles west of the capital, the two forces collided at Champion’s Hill. Pemberton chose the best defensible terrain in the area and deployed his divisions with William W. Loring situated on the right, Bowen covering the center, and Major General Carter L. Stevenson on the left. McPherson’s corps attacked the main Confederate positions across the road over Champion’s Hill, and the concentrated Union pressure forced Pemberton to shift Bowen to support Stevenson. Determined Confederate counterattacks initially drove McPherson’s men back, but the Rebels soon recoiled before superior numbers. McClernand initially failed to follow Grant’s orders to advance, and XIII Corps did not strike the depleted Confederate line until late afternoon. Unable to arrest the Union advance, portions of Pemberton’s line broke, forcing him to withdraw to prepared positions along the Big Black River. Confederate losses were 3,624, while Grant reported total losses of 2,441.

The next day at the Big Black River, Pemberton displayed tactical ineptness by misusing the natural obstacle of the river. High bluffs bordered the west side of the river crossing but, unaccountably, Pemberton chose to defend on the comparatively level terrain east of the river. He arrayed his artillery in a mile-long series of strong points, connected by infantry breastworks, along the east side of the river and west of a small waterway that made the Confederate positions and island. Perhaps he believed he could halt Grant on the level ground that fronted his main positions.

The initial Federal advance, however, did not come over this flat land. Under cover of darkness Sherman came around on the north and crossed some of his troops on a pontoon bridge. At daylight, Union infantry advanced to the river concealed by a copse of woods north of the Rebel defenses. Outflanked and with his men retreating in disorder, Pemberton ordered a total withdrawal. Grant lost fewer than 300 men, and Pemberton listed 1,024 as casulaties. When the Rebel line collapsed, Yankee infantrymen leaped on the stringers of the railroad bridge and “ran across them like squirrels.” At other points the Federals charged across the river on trees felled as footbridges.

After the fiasco at the river crossing, Pemberton rushed back to Vicksburg, with the Union army in hot pursuit. He wrote Johnston that his position was untenable and he felt compelled to return to Vicksburg’s defenses. Cut off east of the river, Loring marched his division on a circuitous route to join Johnston.

Johnston again ordered Pemberton to evacuate Vicksburg and march northeast to join him in a coordinated attack on Grant In response to Johnston’s message, Pemberton held a council of war and his officers unanimously elected to remain within the confines of the city’s substantial defenses. Boasting more than 100 field pieces, the Confederate emplacements ran along the crest of a wooded ridge north of the city, thence south and westward to the river. Numerous deep ravines and streams, favoring the defender, cut the rugged, brush-covered terrain. Pemberton wrote Johnston that “I still conceive it [Vicksburg] to be the most important point in the Confederacy.”

By this time, however, the retention of Vicksburg was only a symbolic, political, and psychological gesture. The city had lost its strategic significance when Porter’s gunboats successfully ran the batteries in April With Union vessels both north and south of the city, steamboats could no longer reach the railhead in Vicksburg. Thus, along with Memphis and New Orleans, the Confederacy had lost its last rail link to the Trans-Mississippi Department.

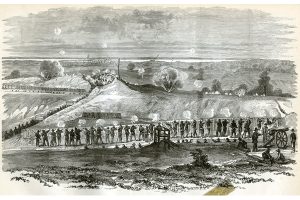

Grant, apprehensive about an extended siege, made two costly frontal assaults on Vicksburg. At 2:00 P.M. on 19 May, he ordered an attack along the main roads leading into the Rebel bastion. Although several Union companies advanced to the outer parapets, the defenders drove them back with heavy casualties.

During the next few days, Grant’s engineers alleviated his supply problems somewhat. North of Vicksburg the engineers constructed a pontoon bridge that allowed supplies to be unloaded at the landing near Haynes’s Bluff on the Yazoo River From there and from Chickasaw Bayou, wagon trains transported vital rations, medical supplies, clothing, and ammunition around enemy positions to grant’s three corps investing Vicksburg.

On the 22nd, under cover of a thunderous bombardment, Grant launched another frontal assault on the Confederate earthworks. By midafternoon Grant determined that the attack had failed, but he received a note from McClernand claiming that he had taken three of the enemies’ outer parapets and that “the flag of our beloved country floated over the stronghold of Vicksburg.” McClernand asked for reinforcements and for Grant to press his attack so that McClernand could consolidate his gains. Grant passed the note to Sherman, commenting, “If only I could believe it.” Grant hesitantly renewed the attack.

Unfortunately for the Federals, McClernand was wrong, and Grant’s infantry fell back with bloody losses of over 3,000. The dead lay decomposing in the sun for three days before the stench prompted both sides to agree on a cease-fire to bury the rotting corpses The only thing McClernand captured were a few advanced picket posts outside the Confederate defenses.

Shortly, copies of the St. Louis Democrat arrived with a vainglorious account of the battle, along with a congratulatory order from McClernand to his corps. In the most laudatory terms he congratulated his troops and asserted that if at Champion’s Hill and Vicksburg the other corps “had only done their duty, the stronghold would now be ours.” Infuriated by McClernand’s misrepresentations, Sherman and McPherson sent heated letters to Grant. Grant, also outraged at McClernand’s blatant attempt to further his political career at the expense of others, queried McClernand concerning the accuracy of the report. Grant also asked why he had not received a copy of the order, as regulations required. McClernand affirmed the accuracy of the article and blamed his adjutant for not forwarding a copy of the order to Grant. Grant relieved this disloyal officer and appointed Major General O.C. Ord to command XIII Corps. The entire army rejoiced at McClernand’s departure, while Ord’s appointment greatly improved the efficacy of the XIII Corps.

In twenty days, Grant’s army marched over 180 miles from Bruinsburg to invest Vicksburg. Along the way it captured Jackson and destroyed the city’s arsenal and burned anything of military value. During the march, Grant’s troops fought five major engagements and captured over 6,000 prisoners and 88 artillery pieces.

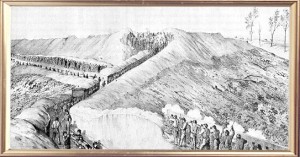

Forced into siege warfare, Grant ordered his engineers to dig a series of trenches along the seven miles of Confederate earthworks. When completed, the Union entrenchments measured almost fifteen miles. Sherman occupied the right, McPherson the center, and McClernand, who would remain in command until 19 June, the left; both Sherman and McClernand extended their lines to the Mississippi north and south of Vicksburg. Initially the trenches were about 600 yards away from the Confederate outer defenses, but Union soldiers dug a series of zigzag saps and parallels that approached to within a few feet of the Rebel positions. At night soldiers from both sides left their trenches to swap tobacco, coffee, and newspapers. By the end of May, 50,000 Union soldiers occupied the trenches, and two weeks later 21,000 more joined the Federal army surrounding Vicksburg.

Forced into siege warfare, Grant ordered his engineers to dig a series of trenches along the seven miles of Confederate earthworks. When completed, the Union entrenchments measured almost fifteen miles. Sherman occupied the right, McPherson the center, and McClernand, who would remain in command until 19 June, the left; both Sherman and McClernand extended their lines to the Mississippi north and south of Vicksburg. Initially the trenches were about 600 yards away from the Confederate outer defenses, but Union soldiers dug a series of zigzag saps and parallels that approached to within a few feet of the Rebel positions. At night soldiers from both sides left their trenches to swap tobacco, coffee, and newspapers. By the end of May, 50,000 Union soldiers occupied the trenches, and two weeks later 21,000 more joined the Federal army surrounding Vicksburg.

Grant commanded a large infantry force but suffered a paucity of artillery, especially heavy siege guns. He had to depend on six thirty-two pounders and a battery of heavy cannon borrowed from Porter’s gunboats. Porter’s boats also mounted several large mortars, and Grant’s men fabricated several more by boring out large logs and reinforcing them with iron bands. Although they were not designed for the task, Grant employed his field artillery as his major weapon to breach the formidable Rebel earthworks. By the end of June, the Federal army trained 220 guns on Vicksburg. Unlike the Confederates, the Union artillerymen drew upon “an inexhaustible supply of ammunition” and “used it freely.”

Beginning on 23 May, Grant’s pioneers, infantrymen, and hired black laborers dug a series of trenches containing numerous rifle pits with overhead cover of timber and sandbags. At many points the opposing fighting positions were close enough for the Rebels and Yankees to banter back and forth. The Union soldiers threw hardtack over to the defenders, while the Confederates responded with twists of tobacco. Often, however, the exchanges were hand grenades.

Grant’s men also dug a series of mines, or tunnels, under the Confederate lines and packed them with black powder to blow gaps in the Confederate defenses. At 3:00 P.M. on 25 June the Federals exploded the first of these mines. When the mine detonated, it blew tons of earth and several Confederate workers into the air, some of the men landing relatively unhurt in the Union lines. Two regiments charged into the breach, but the Confederates repulsed the Union infantry with hand grenades and short-fused artillery shells rolled into the crater. Confederate losses numbered eighty-eight, while grant reported about thirty of his men killed or wounded during the combat. On 1 July the Federals detonated another mine, killing and wounding several Confederates, but they did not rush into the huge chasm fearing another loss of men in an abortive charge. Confederate countermines failed to block any of the Union tunnels.

Forced to change his plans, Johnston concentrated on raising an army large enough to lift the siege, or at least open a gap in the Union lines long enough for Vicksburg’s defenders to escape. Through May and part of June, he repeatedly requested reinforcements, but few were forthcoming. He managed to build an army of 31,000, but, considering Grant’s overwhelming numbers, Johnston needed more men. Johnston, along with Lieutenant General James Longstreet and P.G.T. Beauregard proposed that reinforcements from the Army of Northern Virginia join General Braxton Bragg, who planned to open an offensive against Major General William Rosecrans in Tennessee. Robert E. Lee’s opposition to depleting his forces east of the Appalachians scuttled their plans. Lee averred that his planned campaign into Pennsylvania would relieve the pressure on Vicksburg.

Pemberton could expect little relief from the Trans-Mississippi either. Johnston had scoured the department and gathered all the troops available. Across the river on 7 June, Major General John G. Walker attempted to destroy Grant’s supply depot at Milliken’s Bend, but his attack came too late to help Pemberton. (Milliken’s Bend was the first major engagement of the war in which black combat troops participated.) Therefore, on 15 June, Johnston informed the War Department that saving Vicksburg was “hopeless.”

Grant realized that Johnston still posed a considerable threat to his rear and took measures to prevent the Confederate general from disrupting his siege. Union troops had already destroyed most of the rail lines around Jackson and burned the majority of the rolling stock. Grant dispatched a division to destroy all the remaining bridges between the opposing armies and to make the roads as impassable as possible. This forced Johnston to rely on an insufficient number of wagons and carts to bring supplies to his army. Grant’s foraging parties also thoroughly scavenged the countryside for horses, mules, and all victuals. Without adequate supplies and rations, Johnston’s troops found it almost impossible to sustain themselves within striking distance of Grant.

Grant realized that Johnston still posed a considerable threat to his rear and took measures to prevent the Confederate general from disrupting his siege. Union troops had already destroyed most of the rail lines around Jackson and burned the majority of the rolling stock. Grant dispatched a division to destroy all the remaining bridges between the opposing armies and to make the roads as impassable as possible. This forced Johnston to rely on an insufficient number of wagons and carts to bring supplies to his army. Grant’s foraging parties also thoroughly scavenged the countryside for horses, mules, and all victuals. Without adequate supplies and rations, Johnston’s troops found it almost impossible to sustain themselves within striking distance of Grant.

Concerned nevertheless about his position between two enemy forces, Grant placed Sherman in command of all troops from Haynes’s Bluff to the Big Black River and directed him to deploy some of his 34,000 men along a defensive line about fifteen miles east of Vicksburg. Grant believed Vicksburg to be so important to the South that the Confederates “would make the most strenuous efforts to raise the siege.” He also ordered his cavalry to guard the fords on the Big Black River and monitor Johnston’s movements. The Union army now faced both west and east, prepared both to besiege Vicksburg and defend itself from any Rebel attack.

Although Pemberton had begun stockpiling provisions in March, conditions inside Vicksburg rapidly deteriorated. Both citizens and soldiers sought shelter from incessant bombardments in cellars or caves dug into the city’s numerous hillsides, often discovering large rattlesnakes sharing their beds in these caves. Drinking water became scarce and the food supply dwindled. Mule meat replaced beef and pork, and the bread ration was halved, then halved again. The Confederates experimented with a mixture of ground peas and corn meal, but this concoction “had the properties of Indian rubber and was worse than leather to digest.”

Johnston held few options for extricating Pemberton’s trapped men. He considered the possibility that a coordinated assault on both Grant and Sherman might prevent either Union force from coming to the aid of the other and open a way out for Pemberton. Outnumbered, the Confederates would have to rely on a Union blunder to open a path for escape. This option required precise timing and organization, and with the uncertain communications between himself and Pemberton, Johnston abandoned this plan.

On 28 June, Johnston sent a courier to Pemberton with a message describing a final plan to break the siege. Operating on Pemberton’s assumption that he could hold Vicksburg until 10 July, Johnston would initiate a diversionary attack on 7 July. He believed such an attack would disrupt Grant’s attention long enough for Pemberton to fight his way out of the encircled city. Johnston’s message never reached Pemberton.

On 3 July, after a forty-six-day siege, Pemberton concluded that his beleaguered men could no longer stand the rigors of sustained combat and starvation. Consequently, at about 10:00 A.M., under flags of truce, he arranged a meeting with Grant between the lines. On Independence Day 1863, Pemberton surrendered 2,166 officers, 27,230 enlisted men, 172 cannon, and 60,000 long arms. Many of the long arms were modern Enfield rifles, smuggled in from England, which Grant used to reequip his volunteers, who had been carrying older smoothbore muskets.

On 3 July, after a forty-six-day siege, Pemberton concluded that his beleaguered men could no longer stand the rigors of sustained combat and starvation. Consequently, at about 10:00 A.M., under flags of truce, he arranged a meeting with Grant between the lines. On Independence Day 1863, Pemberton surrendered 2,166 officers, 27,230 enlisted men, 172 cannon, and 60,000 long arms. Many of the long arms were modern Enfield rifles, smuggled in from England, which Grant used to reequip his volunteers, who had been carrying older smoothbore muskets.

The entire Union force, both soldiers and sailors, celebrated the Fourth of July with the ceremony of surrender. The army marched into the city “with colors flying and bands playing.” On the river vessels, “decorated with flags and sailors in their holiday dress, and guns firing” joined in the victory jubilation. Among the gutted houses and debris of war, magnanimous Union infantrymen shared their bacon and hardtack with the ravenous occupants of Vicksburg, but Independence Day was not celebrated in Vicksburg again until World War II, eighty-one years later. The National Cemetery at Vicksburg contain the graves of 16,822 Union soldiers killed near the city.

The capture of Vicksburg solidified Grant’s reputation as a fighting general, prepared to win the war despite the casualties. Along with his later victories near Chattanooga, Vicksburg guaranteed his spectacular rise to lieutenant general and commander of all Union armies.

The loss of Vicksburg cut off the Confederacy from replacements, horses, cattle, pigs, sugar, and salt available from Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. When Port Hudson fell a few days later, President Abraham Lincoln commented that the Mississippi River “again goes unvexed to the sea.”

- Stanley S. McGowen

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 2021-2027]

A wonderful summary. As we know Gettysburg gets most of the attention but those of us in the west know about Vicksburg. I had four GGreat Uncles there and one, Lt. Orlando Graham in the 4th Mn., was in the first regiment to enter Vicksburg after the surrender.