Considered by many historians to be the turning point of the Civil War, the Gettysburg campaign began on 3 June 1863 when elements of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began leaving their positions near Fredericksburg and heading for the Shenandoah Valley. Lee planned a raid into Pennsylvania to relieve the strained Virginia countryside, disrupt Union economic security east of the Susquehanna River, and bring foreign recognition to the Confederacy.

After Stonewall Jackson’s death in May 1863, Lee reorganized his 80,000-man army into three infantry corps, each consisting of three divisions commanded by a lieutenant general. James Longstreet led I Corps; Richard S. Ewell, II Corps; and Ambrose P. Hill, III Corps. Both Ewell and Hill were new to their positions. Major General James E.B. Stuart led the cavalry of the army. Each division included an artillery battalion, and each corps had two more artillery battalions in reserve. Southern artillery numbered 274 pieces.

Union cavalry led by Major General Alfred Pleasanton battled Jeb Stuart’s cavalry on 9 June in a day-long series of engagements known as Brandy Station. Cavalry of both armies sparred with each other as the Confederate infantry began moving north, the Army of the Potomac under Major General Joseph Hooker moving more slowly while trying to ascertain enemy intentions.

Hooker’s army had contained more than 120,000 men at Chancellorsville, but the mustering out of two-year and nine-month regiments during late May and June reduced its strength to fewer than 100,000. Hooker’s army consisted of seven infantry corps and Pleasanton’s three divisions of cavalry. Each corps was led by a major general, and consisted of either two or three divisions plus an artillery brigade. The corps were led by John F. Reynolds (I), Winfield S. Hancock (II), Daniel E. Sickles (III), George G. Meade (V), John Sedgwick (VI), Oliver O. Howard (XI), and Henry W. Slocum (XII). Brigadier General Robert O. Tyler commanded the five brigades of the Artillery Reserve, which contained 114 cannon of the army’s total of 372 guns.

Troops of Ewell’s II Corps defeated and drove off the Union garrison of Winchester and then swept north, crossed the Potomac River, and entered Maryland and southern Pennsylvania. By late June, Ewell’s men were approaching Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, skirmishing with Union militia west of the Susquehanna. One of Jubal Early’s brigades narrowly missed seizing a bridge over the river at Wrightsville before it was burned by retreating militia. Lee was hampered by the absence of most of his cavalry. Stuart, acting under discretionary orders from Lee, found himself separated from the main army by Union troops and had to circle around behind the northward-moving Yankees before rejoining Lee on 2 July.

Hooker’s troops, meanwhile, crossed the Potomac and headed north to stay between Lee and Washington. Hooker, unhappy with the controls placed on him by the War Department, asked to be relieved of command. His offer was accepted, and on the morning of 28 June, Major General George G. Meade, commander of V Army Corps, was placed in command of the army. Meade took stock of the situation and developed a plan to fight a defensive battle behind Pipe Creek, Maryland.

Lee finally learned from scouts the whereabouts of the Army of the Potomac, canceled his drive on Harrisburg, and ordered a concentration of the army in the mountains between Chambersburg and Gettysburg, the latter a Pennsylvania town of some 2,500 people in Adams County. Union cavalry under Brigadier General John Buford entered Gettysburg on 30 June and sighted rebel infantry to the west.

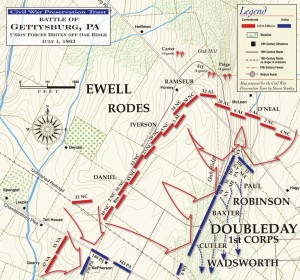

Buford sent word of his discovery to General Reynolds, leader of I Army Corps and commander of Meade’s left wing. Buford decided to hold Gettysburg, and on the morning of 1 July his two brigades, fighting dismounted, fended of Major General Henry Heth’s Division of Hill’s III Corps for several hours until infantry of Reynolds’s corps arrived on Seminary Ridge west of Gettysburg. The Union infantry drove back Heth’s men, but Reynolds was killed during the action and command of the field devolved upon General Howard, commander of the XI Army Corps.

Buford sent word of his discovery to General Reynolds, leader of I Army Corps and commander of Meade’s left wing. Buford decided to hold Gettysburg, and on the morning of 1 July his two brigades, fighting dismounted, fended of Major General Henry Heth’s Division of Hill’s III Corps for several hours until infantry of Reynolds’s corps arrived on Seminary Ridge west of Gettysburg. The Union infantry drove back Heth’s men, but Reynolds was killed during the action and command of the field devolved upon General Howard, commander of the XI Army Corps.

As the troops of I Army Corps, now led by Major General Abner Doubleday, deployed along McPherson’s Ridge, two of Howard’s divisions moved north through town and deployed in the fields to guard against Confederates of Jubal Early’s division, heading south toward Gettysburg. Further Confederate reinforcements from Robert Rodes’s division of Ewell’s corps and William D. Pender’s of Hill’s gave Lee, who had arrived on the field, a significant numerical advantage over Howard’s divisions.

As the troops of I Army Corps, now led by Major General Abner Doubleday, deployed along McPherson’s Ridge, two of Howard’s divisions moved north through town and deployed in the fields to guard against Confederates of Jubal Early’s division, heading south toward Gettysburg. Further Confederate reinforcements from Robert Rodes’s division of Ewell’s corps and William D. Pender’s of Hill’s gave Lee, who had arrived on the field, a significant numerical advantage over Howard’s divisions.

A concentrated attack by Lee’s men late in the afternoon swamped the Union defenders. Early’s attack flanked Francis Barlow’s division of XI Corps, and the Yankee line north of town broke in confusion. To the west, Doubleday’s brigades put up a stout resistance and caused heavy casualties to Heth’s and Pender’s men before retreating through Gettysburg. Survivors rallied on Cemetery Hill, just south of town, where Howard had placed one of his divisions as a reserve.

The opportune arrival on the field of General Winfield Scott Hancock aided greatly in improving morale. Hancock, Meade’s II army Corps commander, had been sent by his chief to the battlefield to ascertain the situation. Hancock reported favorably on the terrain, and Meade ordered the entire army to concentrate at Gettysburg. Throughout the night and early morning of 2 July, Meade’s divisions marched toward the battlefield. By midmorning, all infantry except VI Army Corps (the largest in the army) had reached the field. General John Sedgwick, commanding VI Corps, promised Meade that his corps, more than thirty miles away when ordered to Gettysburg, would arrive by late afternoon.

By midmorning, Meade’s units had formed the now famous fishhook line of battle. Anchored on the right by the rugged terrain of Culp’s Hill, the line extended westward to Cemetery Hill, then south along Cemetery Ridge to the Round Tops. Cavalry screened both flanks; the compact line allowed Meade to place V Army Corps in reserve pending the arrival of VI Corps. Meade contemplated an attack by his right flank, but unfavorable terrain reports aborted such an effort.

Meanwhile, Lee’s divisions had failed to follow up their success of 1 July. That afternoon, as Union survivors assembled on the high ground south of town, Lee advised Ewell that his men should size Cemetery Hill “if practicable.” Ewell and other officers decided that an attack was not possible and thus failed to drive the enemy from Cemetery Hill. Lee, disappointed, nevertheless decided to continue the battle the next day, in spite of protests by General Longstreet, his I Corps commander.

Longstreet, seeing the strength of the Union position, advised a flanking move designed to force the Yankees to retreat, but Lee overruled his chief lieutenant and offered an offensive on 2 July. Longstreet, using his two available divisions (those of Lafayette McLaws and John B. Hood), would attack the Union left flank. A.P. Hill’s troops, occupying the Confederate center, would assist Longstreet as the opportunity availed itself. Ewell’s three divisions, on the left, would attack Meade’s right and pin it in place to prevent reinforcements from helping the Union left flank. If all went well, Meade’s troops would be driven from their positions.

Longstreet, seeing the strength of the Union position, advised a flanking move designed to force the Yankees to retreat, but Lee overruled his chief lieutenant and offered an offensive on 2 July. Longstreet, using his two available divisions (those of Lafayette McLaws and John B. Hood), would attack the Union left flank. A.P. Hill’s troops, occupying the Confederate center, would assist Longstreet as the opportunity availed itself. Ewell’s three divisions, on the left, would attack Meade’s right and pin it in place to prevent reinforcements from helping the Union left flank. If all went well, Meade’s troops would be driven from their positions.

Events on the Confederate side for the rest of the morning and afternoon are controversial to the extreme. Longstreet waited for an Alabama brigade to arrive before beginning his march to the Union left flank. Proponents of Lee argued later that Longstreet’s delay was unnecessary and resulted in a lost opportunity to destroy Meade’s army that morning before it could entirely assemble on the field.

Forty-seven Civil War reenactors representing the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry arrive at the Gettysburg National Military Park in preparation for this weekends Civil War reenactment, and next week’s official commemorative observances of the 150th Anniversary of the important battle.

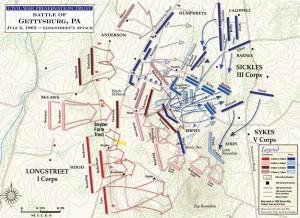

Controversy also erupted on Cemetery Ridge. General Daniel Sickles, the political general in charge of III Army Corps, stationed on the army’s left, was unhappy with the terrain north of Little Round Top and sought permission to change his deployment. Meade ordered his testy subordinate to remain in line and deploy according to general instructions received earlier in the morning. Sickles sent Colonel Hiram Berdan’s sharpshooters out to Seminary Ridge to reconnoiter. The green-clad sharpshooters encountered Richard H. Anderson’s Division of Hill’s III Corps maneuvering into position to await Longstreet’s arrival on its right flank. Sickles, uneasy over learning about the enemy, took it upon himself to advance his two divisions to occupy higher ground to his front along the Emmitsburg Road. The V-shaped salient that Sickles occupied isolated his corps from Hancock’s. Meade did not learn about Sickle’s disobedience of orders until late in the afternoon, when he called his corps commanders together for a conference, just as VI Army Corps was sighted on the Baltimore Pike.

Meade inspected Sickles’s faulty position and ordered a withdrawal, but it was too late. Longstreet’s two divisions had finally moved into position on Anderson’s left, and at 4:00 P.M. the Confederate artillery opened fire on Sickles’s line, just as Meade was ordering Sickles to return to Cemetery Ridge. Meade quickly countermanded the retreat order and instead went about finding reinforcements for Sickles.

Meade inspected Sickles’s faulty position and ordered a withdrawal, but it was too late. Longstreet’s two divisions had finally moved into position on Anderson’s left, and at 4:00 P.M. the Confederate artillery opened fire on Sickles’s line, just as Meade was ordering Sickles to return to Cemetery Ridge. Meade quickly countermanded the retreat order and instead went about finding reinforcements for Sickles.

Longstreet’s attack began on the right, with Hood’s division, which swept forward over rough terrain and almost seized Little Round Top, left unguarded by Sickles’s movement. Luckily, Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren, Meade’s chief engineer, had climbed the hill and noticed the beginning of the Southern advance. He called for reinforcements and personally commandeered a brigade from the advancing V Army Corps and ordered it to occupy Little Round Top. Colonel Strong Vincent’s four regiments deployed on the southern end of Little Round Top just in time to meet elements of Hood’s division. After a fierce struggle, climaxed by the epic stand of the 20th Maine, and arrival of further reinforcements, Little Round Top remained firmly in Union hands.

Longstreet’s divisions crashed into Sickles’s men and mad famous a field of wheat (now known as the Wheatfield), an outcrop of granite boulders (Devil’s Den), and a large peach grove (now known as the Peach Orchard). Reinforcements from Hancock’s II Army Corps, Doubleday’s I, Sedgwick’s VI, and even from Slocum’s XII Army Corps, ordered away from their entrenchments on Culp’s Hill, finally stemmed the Confederate assault. By nightfall, Sickles’s corps had been pushed back to Cemetery Ridge, with Sickles himself wounded in a leg, which was amputated that night.

On the Union right, Edward Johnson’s division of Ewell’s corps moved forward in the coming darkness and occupied a section of abandoned Union earthworks on the eastern side of Culp’s Hill. A lone brigade of New Yorkers led by Brigadier General George S. Greene held the crest of the hill, and, aided by reinforcements, fended off Johnson’s attacks. Two brigades of Early’s division stormed up the steep slopes of Cemetery Hill, drove off some XI Corps infantry, and fought hand-to-hand with Yankee gunners defending their batteries, but had to retreat when reinforcements assisted in driving them back.

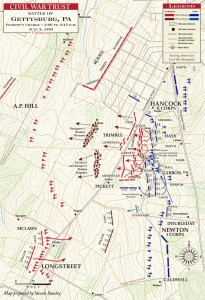

Having been repulsed on both Union flanks, General Lee decided to attack the Union center on 3 July. That morning, a terrific battle erupted on the Union right as troops from VI and XII Army Corps dueled with Ewell’s men for possession of the works on Culp’s Hill. By late morning, the weight of Union infantry and artillery drove back the rebels and solidified the Federal position.

Colonel Edward P. Alexander, acting under Lee’s instructions, assembled more than 100 artillery pieces to bear on the Union center. The rebel artillery opened fire shortly after 1:00 P.M. and was answered by more than eighty Federal cannon. The artillery duel continued for more than an hour, after which an infantry force various estimated at between 10,500 and 15,000 soldiers moved forward to attack Hancock’s II Army Corps at the Federal center. Composed of Major General George Pickett’s three Virginia brigades, supported by brigades from Heth’s and Pender’s divisions, Longstreet’s assault, popularly known as Pickett’s Charge, moved against the Union center across a mile of open fields.

Colonel Edward P. Alexander, acting under Lee’s instructions, assembled more than 100 artillery pieces to bear on the Union center. The rebel artillery opened fire shortly after 1:00 P.M. and was answered by more than eighty Federal cannon. The artillery duel continued for more than an hour, after which an infantry force various estimated at between 10,500 and 15,000 soldiers moved forward to attack Hancock’s II Army Corps at the Federal center. Composed of Major General George Pickett’s three Virginia brigades, supported by brigades from Heth’s and Pender’s divisions, Longstreet’s assault, popularly known as Pickett’s Charge, moved against the Union center across a mile of open fields.

Union artillery blasted the attackers, and by the time the spearhead reached the Union line, the assault had been largely broken up and disorganized. Several hundred Virginians led by Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead seized some Union cannons at the Bloody Angle, but were driven off or captured by the Union defenders. The failed charge ended the major action at Gettysburg, although some V Army Corps troops on Meade’s left charged across the Wheatfield and mauled one of Longstreet’s Georgia brigades.

Meanwhile, cavalry actions took place on both flanks. Jeb Stuart, with several brigades of cavalry, moved toward the right rear of the Union army but was met by Yankee cavalry, including the Michigan brigade led by George A. Custer. After a furious action involving both mounted and dismounted troopers, Stuart admitted defeat and withdrew.

On the Confederate right, two brigades of Yankee cavalry moved to attack but were repulsed, with Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth losing his life during a confused charge over rough terrain in front of Big Round Top. The 6th U.S. Cavalry was detached to intercept a rebel forage train said to be operating near Fairfield (southwest of Gettysburg), but was met by a brigade of rebels and largely destroyed.

Both armies remained in position on 4 July, which was a day of rain. Lee’s army of 75,000 effectives had suffered 28,000 casualties and thus the general decided to retreat to Virginia. The retreat began in the rain of 4 July as a wagon train estimated at nineteen miles long carried thousands of wounded men south toward the Potomac.

Meade’s army suffered casualties of 3,149 killed, 14,501 wounded, and 5,157 captured or missing, for a total of 22,807. Of seven infantry corps commanders, one (Reynolds) was killed and two (Hancock and Sickles) wounded. Two division commanders and eleven brigade leaders were also hors de combat, the combination of which severely disabled the Army of the Potomac. As a result, Meade directed a cautious pursuit, which was highlighted by a series of cavalry actions as Yankee cavalry attempted to interdict Lee’s wagon trains.

Lee’s army halted at Williamsport, Maryland, and entrenched. The Potomac River, swollen by the rains, prevented an easy crossing, made all the more serious after Union cavalry operating from Harper’s Ferry destroyed a pontoon bridge erected during the march north. Meade’s army deployed to face the enemy and probed the strong defenses. A council of war voted not to attack, but Meade overruled his subordinates and ordered the assault. however, Lee’s army slipped across the river via a new bridge and the Yankee attack merely netted some stragglers and the rear guard on 14 July. The Army of the Potomac crossed into Virginia soon thereafter and the campaign ended officially on 1 August, when both armies came to a halt in the Loudoun Valley.

- Richard A. Sauers

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 827-838]

For further reading:

Cox, John D. [amazon_link id=”0878397043″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Gettysburg: A History for the People[/amazon_link] (2013).

Cox, John D. [amazon_link id=”0306812347″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Culp’s Hill: The Attack and Defense of the Union Flank, July 2, 1863[/amazon_link] (2003).

Williams, Jeffrey S. [amazon_link id=”0989042103″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Muskets and Memories: A Modern Man’s Journey through the Civil War[/amazon_link] (2013).