The unexpectedly fierce fight at Falling Waters, Maryland, wrote an anticlimactic close to the Gettysburg campaign. Despite the recklessness of one Union cavalry general, his brother officers managed to cut off and capture 700 infantrymen from the Army of Northern Virginia’s rear guard.

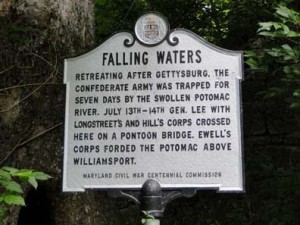

After the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia retreated toward the Potomac River, seeking safety in Virginia. Heavy rains had turned the Potomac into an unfordable torrent, however, stranding the rebels within easy reach of the Union Army of the Potomac. Lee met the crisis with characteristic resourcefulness, having his divisions dig a line of earthworks stretching from Williamsport, Maryland, to Downsville, ten miles to the southeast. Sheltering behind their fortifications, the rebels waited for the Potomac to fall. By 13 July, the Potomac’s water level had subsided sufficiently for Lee’s infantry to ford the river at Williamsport. Confederate engineers had also placed a pontoon bridge at Falling Waters, about four miles downstream. Soon after sunset, Lee’s troops began crossing the Potomac at both locations.

After the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia retreated toward the Potomac River, seeking safety in Virginia. Heavy rains had turned the Potomac into an unfordable torrent, however, stranding the rebels within easy reach of the Union Army of the Potomac. Lee met the crisis with characteristic resourcefulness, having his divisions dig a line of earthworks stretching from Williamsport, Maryland, to Downsville, ten miles to the southeast. Sheltering behind their fortifications, the rebels waited for the Potomac to fall. By 13 July, the Potomac’s water level had subsided sufficiently for Lee’s infantry to ford the river at Williamsport. Confederate engineers had also placed a pontoon bridge at Falling Waters, about four miles downstream. Soon after sunset, Lee’s troops began crossing the Potomac at both locations.

As luck would have it, Major General George Gordon Meade, the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, chose the evening of the 13th to authorize a strong reconnaissance in force along Lee’s lines commencing the next day at 7:00 A.M. Four hours before the scheduled foray, Brigadier General H. Judson Kilpatrick, commanding the 3rd Division in the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, learned that enemy pickets had disappeared from his front. Suspecting a Confederate evacuation, Kilpatrick hurled his division toward the Potomac. At 6:00 A.M., Kilpatrick’s vanguard, Brigadier General George A. Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade, topped the hills overlooking Williamsport and spotted the rear of Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps crossing the Potomac. Custer’s 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment charged into Williamsport, captured some stragglers, and swept others into the water. Local residents informed Kilpatrick that many other rebels had marched to Falling Waters, and he told Custer to pursue them.

By 7:00 A.M., Brigadier General John Buford, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s 1st Cavalry Division, discovered that the Confederates had abandoned their trenches around Downsville. Buford immediately sent Kilpatrick a dispatch stating that he intended to thrust the 1st Cavalry Division between Lee’s rear guard and the Potomac.

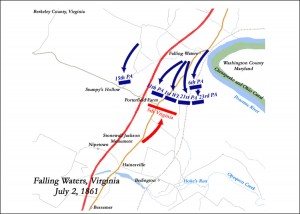

Custer and his lead elements reached a patch of woods within sight of Falling Waters by 7:30 A.M. Two Confederate infantry brigades under Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew manned half a dozen crescent-shaped earthworks on a hill near the crossing. To buy time until the rest of the Michigan Brigade arrived, Custer instructed Major Peter A. Weber to dismount Companies B and F of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, form a skirmish line, and have the men engage the rebels with their seven-shot Spencer rifles. Impatient for a glorious victory, the impetuous Kilpatrick countermanded Custer’s order and sent Weber’s fifty-seven men forward in a suicidal mounted charge.

Mistaking the approaching horsemen for their own cavalry, the Confederates held their fire until the Michiganders rode among them, sabers slashing and revolvers popping. General Pettigrew fell mortally wounded, but his men made short work of their opponents. A bullet smashed through Weber’s skull, and thirty-five of the fifty-seven Union troopers were killed or wounded.

Dismounting the rest of the 6th Michigan, Custer continued the attack in a more sensible fashion, feeding two other regiments into the fray as they reached the scene. Shortly thereafter, Buford swept in behind the beleaguered Confederates. Lee’s engineers cut the Maryland end of the pontoon bridge, leaving 700 of their comrades in Federal hands. Custer’s “Wolverines” also captured three battle flags and two cannon. Custer was conspicuous in the melee that extinguished the final knot of Confederate resistance. As one Michigander wrote his wife: “General Koster…commanded in person and I saw him plunge his saber into the belly of a rebel who was trying to kill him. You can guess how bravely soldiers fight for such a general.”

While the Federals could boast of scorching Lee’s tail, Falling Waters represented a squandered opportunity. Had Kilpatrick restrained himself until Buford got into position, the damage to the Confederates would have been far heavier. By charging two brigades with only two companies, Kilpatrick revealed Union intentions and accelerated his prey’s movement across the Potomac. He tried to conceal his blunder by reporting that his division nabbed more than 1,500 prisoners, a claim that drew a heated denial from General Lee.

While the Federals could boast of scorching Lee’s tail, Falling Waters represented a squandered opportunity. Had Kilpatrick restrained himself until Buford got into position, the damage to the Confederates would have been far heavier. By charging two brigades with only two companies, Kilpatrick revealed Union intentions and accelerated his prey’s movement across the Potomac. He tried to conceal his blunder by reporting that his division nabbed more than 1,500 prisoners, a claim that drew a heated denial from General Lee.

- Gregory J.W. Urwin

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 678-680]

Pingback: Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew, C.S.A. (1828-1863) | This Week in the Civil War