The storming of Fort Wagner typified the poorly planned frontal assaults launched by so many Civil War commanders. It ended in a bloody repulse for the Union attackers. The only consolation the Northern public found in the disaster was the self-sacrificing bravery displayed by the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which was cited as proof that black soldiers could fight and die as well as whites.

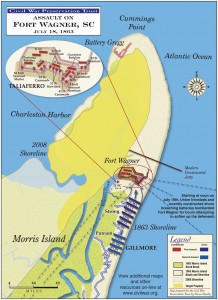

In the summer of 1863, Brigadier General Quincy A. Gillmore, the commander of the Union Department of the South, assembled 11,000 infantry, 350 artillery, and 400 engineers to besiege Charleston, South Carolina. Gillmore intended to seize Morris Island, a 400-acre barrier island on the southern side of Charleston harbor. Cummings Point, the northern tip of Morris Island, sat just 1,390 yards from Fort Sumter, the Confederate stronghold controlling entry to Charleston harbor. Gillmore expected he could easily neutralize Fort Sumter with heavy rifled artillery placed on Cummings Point. That would permit Union warships under Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren to approach Charleston and compel its surrender.

On the morning of 10 July 1863, Union infantry landed on lower Morris Island. Supported by batteries on nearby Folly Island and naval gunfire, the Federals quickly secured most of their objective. All that stood between them and full possession of Morris Island was Fort Wagner, a massive earthwork located 1,200 yards south of Cummings Point.

Fort Wagner stretched 630 feet from east to west, and 275 feet from north to south. its walls consisted of sand piled 30 feet high and held in place by turf, sandbags, and palmetto logs. Two bastions projected from the south wall, which was shielded by a moat 50 feet wide and 5 feet deep. A sturdy bombproof shelter inside the southeast bastion could hold 900 men. Ten heavy guns and one seacoast mortar looked over Fort Wagner’s ramparts, eight of them pointing south.

The only way for Gillmore’s troops to approach Fort Wagner was along a beach no more than 100 yards wide. Bordered on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the west by marshy Vincent’s Creek, this narrow corridor offered the Federals no cover or room to maneuver.

Underestimating Fort Wagner’s strength, Gillmore tried to take the place with a simple surprise attack. Three Federal regiments rushed Fort Wagner at first light on 11 July, but vigilant Confederate defenders blasted their assailants to a standstill, inflicting 339 casualties.

Gillmore decided to storm Fort Wagner again, but only after thorough artillery preparation. Between 12 and 16 July, his engineers erected four batteries containing forty-one guns and siege mortars at ranges of 1,330 to 1,920 yards from the rebel works. In the meantime, the Confederates relieved Fort Wagner’s garrison with fresh troops and increased the posts’s armament to eleven guns and one mortar aiming south, two guns facing seaward, and two field pieces covering the beach.

At 9:00 A.M. on 18 July, Gillmore’s batteries started pounding Fort Wagner. Admiral Dahlgren joined with five monitors, one ironclad frigate, and five wooden gunboats. The Federals subjected Fort Wagner to the most intensive bombardment of the war, but the 9,000 projectiles hurled at the fort did minimal damage. The 1,620-man garrison lost only eight killed and twenty wounded under that terrible iron storm.

At 9:00 A.M. on 18 July, Gillmore’s batteries started pounding Fort Wagner. Admiral Dahlgren joined with five monitors, one ironclad frigate, and five wooden gunboats. The Federals subjected Fort Wagner to the most intensive bombardment of the war, but the 9,000 projectiles hurled at the fort did minimal damage. The 1,620-man garrison lost only eight killed and twenty wounded under that terrible iron storm.

To capture Fort Wagner, Gillmore chose Brigadier General Truman Seymour’s infantry division, fourteen regiments mustering 6,000 effectives. At the head of Seymour’s assault column stood the 54th Massachusetts, the Union army’s model black regiment. The rest of Seymour’s division stretched a mile down the beach.

At 7:45 P.M., the 54th Massachusetts received the signal to commence the assault, and the black soldiers marched resolutely toward Fort Wagner, 1,200 yards away. Confident that Gillmore’s bombardment had either killed the fort’s defenders or driven them toward Cummings Point, Seymour committed his division piecemeal, a brigade at a time. The attacking regiments were shot to pieces as they neared Fort Wagner. Portions of the 54th Massachusetts and other Northern units penetrated the fort at two points, but they lacked the numbers to overrun the hard-fighting garrison. After Seymour’s first two brigades shattered themselves against Fort Wagner, Gillmore refused to let the third go forward and called an end to the slaughter.

This embarrassing failure cost Gillmore 1,515 casualties, including the lives of two brigade commanders. Seymour himself was wounded by a shell fragment. The 54th Massachusetts suffered 272 killed, wounded, and missing, the greatest losses among any of the attacking regiments, but its performance vindicated the Union army’s decision to recruit black soldiers. Wagner’s defenders suffered only 222 casualties. Gillmore would have to resort to a formal siege before the fort fell into his hands two months later.

- Gregory J.W. Urwin

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 760-762]

Pingback: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (1837-1863) | This Week in the Civil War