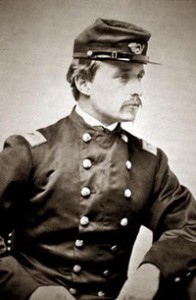

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on 10 October 1837 into great wealth with interlocking kinship ties to the Brahmin families of Forbes, Parkman, Cabot, Lodge, Hunnewell, Sturgis, and Lowell, Robert Gould Shaw had a privileged childhood. His parents insisted on perfectionist ideals. They funded the experimental transcendentalist community at Brook Farm - where Robert attended classes - and were outspoken for the abolition of slavery. Shaw learned lessons of noblesse oblige as he met and interacted with his parents’ circle of friends, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Lloyd Garrison, Henry George, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sydney Howard Gay, Frances Anne Kemble, and Lydia Maria Child, his mother’s closest confidant. Within this circle, Shaw grew up on an ideology of service and principles of moral uplift.

After spending one year at Fordham and five years at schools in Switzerland and Germany, Shaw entered Harvard in 1856. That year he met the Republican Party’s first nominee, John C. Fremont, who was attending the wedding of Shaw’s oldest sister, Anna, to the well-known national orator and, later, editor of Harper’s Weekly, George W. Curtis. Shaw had three other siblings, all sisters, who married prominently to Colonel Charles Russell Lowell, General Francis C. Barlow, and Robert Minturn.

In 1859 Shaw quit Harvard to enter business in the New York City mercantile firm of his uncles. He joined the exclusive 7th New York National Guard, a social club. After the firing on Fort Sumter, Shaw mustered with his regiment and marched down Broadway int he glow of war fever - and with sandwiches from Delmonico’s and a velvet stool to sit upon. The 7th was the first unit to reach Washington after Lincoln’s call for troops and thus won the sobriquet, “the regiment that saved the capital.” When the “Darling Seventh” disbanded after thirty days, without seeing action, Shaw gained a commission as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, commanded by George H. Gordon and stocked with officers from the state’s most prominent families. Shaw proved himself a competent soldier and rose to the rank of captain, having suffered battle wounds during the Shenandoah Valley campaign and the battle of Antietam. In the aftermath of Antietam, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

When Lincoln authorized the enlistment of African-American soldiers, Massachusetts Governor John Andrew quickly gained permission to raise a black regiment. To guarantee success, Andrew sought an officer with prominent family ties, and so turned to the well-connected businessman, John Murray Forbes. Forbes suggested the staunch abolitionist Captain Norwood Penrose Hallowell, 20th Massachusetts Infantry. But Hallowell was from Pennsylvania. Agreeing with Forbes’s second choice, Andrew offered Shaw the colonelcy of what would become the North’s most famous African-American regiment, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry.

Shaw initially declined the offer out of loyalty to his beloved 2nd; but his desire for higher rank, the support of his friends, the pressure applied by his mother, his own moral dilemma, and his recent engagement to marry Annie Haggerty of Lenox helped him to change his mind. the pressure from his mother cannot be overstated. When he accepted the position, she wrote him of her “deep and holy joy” that he had been “willing to take up the cross.”

Insisting upon success - and fearing ridicule - Shaw organized the regiment. He selected officers with firm antislavery views, including a brother of William and Henry James. Shaw wanted only the most educated and physically fit men possible. Altogether, he ordered the rejection of every third man who arrived at the Camp Meigs training center in Readville, Massachusetts. Furthermore, a “Black Committee” of prominent abolitionists was organized to direct the recruiting of men from all the northern states and Canada into this one regiment and to supply the best equipment available. This was their showcase unit. Well-known black leaders, such as Frederick Douglass, John Mercer Langston, O.B. Wells and James Forten, recruited for the regiment. Douglass signed up two of his sons and a grandson of Sojourner Truth. In this manner, the 54th Massachusetts became the most highly selective and well-provisioned regiment of the war.

From the first day in camp, recruits received shoes and uniforms. If they could not read, and there were only a few who could not, they attended reading classes at night. Shaw was a strict disciplinarian who enforced a rigid training schedule. In fact, he was so rigid that he came under criticism from the men, officers, press, and camp commander Colonel Richard Pierce, who ordered Shaw to stop the “severe and unusual punishments not laid down by regulations.”

By 2 May, with 1,000 men under arms, trained and ready, Shaw took a furlough to marry. Four days later, the honeymoon was cut short by orders assigning the regiment to Major General David Hunter and the Department of the South. At the flag presentation ceremony on 18 May, Governor Andrew told the men that the world was watching to see if they would fight like white men. He told Shaw that the experiment was one “full of hope and glory.” Ten days later, Shaw led the men in a parade through Boston and onto the steamer from which they would debark at Port Royal, South Carolina, on 3 June.

The regiment’s first action was a raid into Georgia with Colonel James Montgomery’s 2nd South Carolina Infantry, a regiment recruited from freed slaves. The seaport town of Darien was looted and burned under orders from Montgomery and protests from Shaw. Press reports hurt the reputation of the black fighting men. The regiment stayed mostly in camp for the next month, while Shaw persistently asked for regular combat duty for his men.

The opportunity came when Major General Quincy A. Gillmore, in charge of the operations to reduce Charleston, directed an assault against Battery Wagner on Morris Island. Ordered to support the assault, Shaw moved his regiment to James Island. On 16 July, the regiment stood firm in the face of a surprise attack by a larger Confederate force, losing forty-six men before marching all night to reach a ferry transporting them to Morris Island.

Understanding his duty to show that black men could fight and die like whites, Shaw volunteered to lead the attack on Wagner. At 7:45 P.M. on 18 July, Shaw and his men charged across the open beach and up the sloping walls, directly into Confederate guns and men unhurt by a day-long artillery barrage directed against them. Shaw died at the top of the parapet His regiment, and the thirteen white regiments that followed, did not take the fort. The next day, Confederate gravediggers buried 800 Union soldiers in the sand, and made a statement by burying Shaw face up with twenty of his men face down on top of him.

Understanding his duty to show that black men could fight and die like whites, Shaw volunteered to lead the attack on Wagner. At 7:45 P.M. on 18 July, Shaw and his men charged across the open beach and up the sloping walls, directly into Confederate guns and men unhurt by a day-long artillery barrage directed against them. Shaw died at the top of the parapet His regiment, and the thirteen white regiments that followed, did not take the fort. The next day, Confederate gravediggers buried 800 Union soldiers in the sand, and made a statement by burying Shaw face up with twenty of his men face down on top of him.

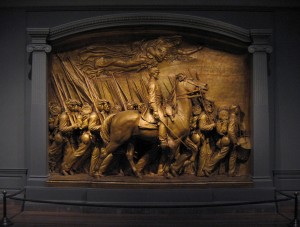

The burial “with his niggers,” as Confederate general Johnson Hagood put it, did not have the effect intended. Instead, the charge, the deaths, and the burial were victories for the abolitionist cause. Nearly fifty poems have been written to commemorate the noble sacrifice. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens crafted a huge bronze monument to the battle set on Boston Common in 1897. A motion picture, Glory (1989), broadcast the story to a wide audience, and books about the young martyr proliferate.

-Russell Duncan

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1744-1745]

Pingback: On this date in Civil War History: Battle of Fort Wagner - July 18, 1863 | This Week in the Civil War