The largest cavalry clash of the Civil War, the Battle of Brandy Station, took place as Robert E. Lee began to move his army north for the invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863. Although the battle was technically a Confederate victory, it demonstrated how much the Union cavalry had closed the gap against its Southern counterpart since the beginning of the war.

After his brilliant victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863, Lee began to plan another invasion of the North. By the end of the month, he began to draw his forces together near Culpeper for a march northward. Lee placed General J.E.B. Stuart and his formidable cavalry at Brandy Station, just east of Culpeper, to screen the rest of Lee’s army as it began to head to the Blue Ridge Mountains on its way to Pennsylvania. On 5 June, Stuart staged a grand review to boost morale and show off his dashing troops. Lee could not attend, so Stuart staged another review on 8 June.

After his brilliant victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863, Lee began to plan another invasion of the North. By the end of the month, he began to draw his forces together near Culpeper for a march northward. Lee placed General J.E.B. Stuart and his formidable cavalry at Brandy Station, just east of Culpeper, to screen the rest of Lee’s army as it began to head to the Blue Ridge Mountains on its way to Pennsylvania. On 5 June, Stuart staged a grand review to boost morale and show off his dashing troops. Lee could not attend, so Stuart staged another review on 8 June.

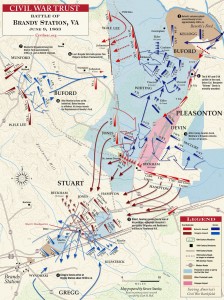

Unknown to Stuart, uninvited guests had observed his second pompous display. General Alfred Pleasanton, with some 8,000 cavalry troops and 3,000 supporting infantrymen, lurked across the Rappahannock River. On the morning of 9 June, Pleasanton struck across the river. He formed his division into two wings. General John Buford’s brigade crossed Beverly Ford on the Rappahannock, while General David Gregg breached Kelly’s Ford six miles downstream later that day. Buford’s troops opened the battle when they struck Confederate cavalry pickets in an early morning haze on 9 June.

Stuart’s distracted troops were caught completely off guard. Buford’s troops pressed on the Confederates under W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee, son of Robert E. Lee. The Federals nearly captured a light artillery unit as they pushed the Confederates away from the Rappahannock. Around 10:00 A.M., Wade Hampton finally counterattacked for Stuart and turned back the Yankee offensive. Generals Rooney Lee and “Grumble” Jones also attacked Buford’s forces from other sides. The battle surged back and forth around St. James Church. Buford began to concentrate on the Confederate left, around the Cunningham farm.

Around noon, the second part of Pleasanton’s cavalry joined the attack. David Gregg’s forces, delayed by the slow arrival of one division, stormed across Kelly’s Ford around noon and came in directly behind the Confederates. The attack was potentially disastrous for Stuart’s cavalry, and they were in danger of being routed by the upstart Union troopers. Gregg entered Brandy Station, sweeping Confederate pickets from his path. He was heading for Fleetwood Hill, just outside Brandy Station. This elevation was the key to the battlefield. Whoever controlled this hill possessed a great advantage.

Around noon, the second part of Pleasanton’s cavalry joined the attack. David Gregg’s forces, delayed by the slow arrival of one division, stormed across Kelly’s Ford around noon and came in directly behind the Confederates. The attack was potentially disastrous for Stuart’s cavalry, and they were in danger of being routed by the upstart Union troopers. Gregg entered Brandy Station, sweeping Confederate pickets from his path. He was heading for Fleetwood Hill, just outside Brandy Station. This elevation was the key to the battlefield. Whoever controlled this hill possessed a great advantage.

A single heroic act may have saved the day for the Confederates. At the bottom of Fleetwood Hill sat Lieutenant John Carter with a six-pound cannon, left there for want of ammunition. Major Henry McClellan, Stuart’s aide, frantically signaled Carter to bring the gun to the crest of Fleetwood Hill. Carter quickly unlimbered the gun and hauled it to the top of the hill where he packed it with bits of metal and substandard shells. There was enough powder for only one shot.

Meanwhile, Gregg was leading his troops towards Fleetwood Hill. As his forces began to ride up the hill, Carter fired the one blast his cannon had. It hit nothing, but it stopped the Yankees in their tracks. Colonel Percy Wyndham, the leader of the Federal column, suspected that the shot came from a line of guns set just over the top of the hill. He paused his men to wait for Gregg and the rest of the force. The ploy bought critical time for the Confederates. McClellan summoned part of Jones’s brigade toward Fleetwood Hill. A frantic, hand-to-hand struggle for the hill ensued. The two sides literally charged through each other, and the summit of the hill changed hands numerous times.

Five miles south of Brandy Station yet another battle was raging. Colonel Alfred Duffie had split from Gregg’s wing to cover the Union left flank. He encountered two regiments from Hampton’s division and soundly defeated the rebels. Duffie then rode toward Brandy Station on a route that would have brought him directly into the Confederate rear. The move might have won the battle for the Union, but Duffie received an order to rejoin Gregg. This forced his men to backtrack for several miles, and it effectively took them out of action. They were the only division in Pleasanton’s cavalry that could not embroider “Brandy Station” on its flag.

Back at Fleetwood Hill, the action continued. Buford’s men, pinned down by the triple Confederate attack earlier, now surged ahead when the Confederates had to turn their attention toward Gregg’s attack from the far right. This Union advance only fueled the chaos of the battle. The day saw many spectacular cavalry charges and saber fights as well as intense combat by dismounted troops. Fighting continued until the late afternoon, and the Confederates finally controlled Fleetwood Hill. Both sides were exhausted.

Back at Fleetwood Hill, the action continued. Buford’s men, pinned down by the triple Confederate attack earlier, now surged ahead when the Confederates had to turn their attention toward Gregg’s attack from the far right. This Union advance only fueled the chaos of the battle. The day saw many spectacular cavalry charges and saber fights as well as intense combat by dismounted troops. Fighting continued until the late afternoon, and the Confederates finally controlled Fleetwood Hill. Both sides were exhausted.

The Union cavalry evacuated the battlefield by the early evening after an intense ten-hour engagement. Because the Confederates held the field, Stuart could call it a victory. The Confederates inflicted some 934 casualties while sustaining 525. But most observers realized what had happened. The Union cavalry had surprised the Southerners and matched them blow for blow for the first time during the war. It removed the sense of inferiority that had haunted the Federal troopers in previous engagements. The huge psychological advantage that the Confederate cavalry had enjoyed throughout the war was lost in a single day. With a new sense of confidence, the Union cavalry fought well in succeeding battles. At Gettysburg, it fought Stuart’s troops to a standstill as the Confederates tried to disrupt Union lines from the rear. Stuart’s troops held Brandy Station, but were embarrassed by the tremendous difficulty they had in breaking even.

-Richard D. Loosbrock

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 271-274.]

Join the Civil War Trust’s efforts to save a crucial 56-acre parcel at Fleetwood Hill by clicking here.