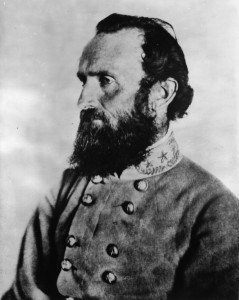

Thomas Jonathan Jackson was known as “Stonewall,” but “the Christian soldier” would have been a more appropriate title. his military experience was in artillery, yet he excelled as a commander of infantry. Soldiers adored him, despite the fact that he was a tight-lipped, stern-disciplined eccentric. Fellow generals were in awe of him because his silence concealed a fiery combativeness smoldering deep inside. Although he was in the field but two years during the Civil War, he more than any other individual became the radiant hope of the Southern cause. more astounding are the number of people - past and present - who assert that had he not died in 1863, his genius would have enabled the Confederate States to achieve their independence. Such was the mystique of Thomas J. Jackson.

His life personifies the American rags-to-riches story. It began with a childhood so sad that Jackson would not talk about it except with the women he loved.

Jackson was born near midnight on 20-21 January 1824, at the village of Clarksburg in the mountains of what was then northwestern Virginia. His father, Jonathan Jackson, was a struggling, ne’er-do-well attorney whose debts overwhelmed the obligations of caring for a young wife and three small children. Thomas was only two when his father and a sister died of typhoid fever. For four years Mrs. Julia Neale Jackson and her children were wards of the town of Clarksburg. Young Tom Jackson’s clothing consisted of a torn shirt and one pair of ragged trousers.

Jackson was born near midnight on 20-21 January 1824, at the village of Clarksburg in the mountains of what was then northwestern Virginia. His father, Jonathan Jackson, was a struggling, ne’er-do-well attorney whose debts overwhelmed the obligations of caring for a young wife and three small children. Thomas was only two when his father and a sister died of typhoid fever. For four years Mrs. Julia Neale Jackson and her children were wards of the town of Clarksburg. Young Tom Jackson’s clothing consisted of a torn shirt and one pair of ragged trousers.

His mother remarried, but Jackson’s stepfather was financially unable to care for the children. Hence, they were sent individually to live with relatives. Jackson’s mother died within a year. At an early age, the boy was an orphan too familiar with death.

He grew up at Jackson’s Mill, the family estate some twenty miles south of Clarksburg. Jackson was under the care of an uncle, Cummins E. Jackson, who ran lumber and grist mills, raised crops and livestock, operated a racetrack, and pursued other businesses - all with little regard for honesty or decency. Cummins Jackson gave his nephew security; he was incapable of the familial love a lonely boy needed. Tom Jackson became accustomed to hard work. He also became a loner - shy, withdrawn, and introspective. What education he received came from a love of reading and local tutors who taught him basic rudiments from time to time.

In 1842, Jackson secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy. The opportunity came only because the boy who had originally been picked from his congressional district decided against a military education. Few youths have ever entered West Point with less academic preparation than 18-year-old Tom Jackson. In appearance and personality, he was an awkward, almost comical mountaineer devoid of social graces. No one gave young Jackson much chance of completing the requirements at what was then America’s finest engineering college. Yet no one was aware of the iron self-discipline inside the unimpressive lad.

Jackson realized that West Point probably offered him the only chance for a college education that he would ever have. If he could graduate, a respectable career as an army officer would elevate him far above his orphan background. So the proud mountain boy developed impassivity as a protection while he concentrated all of his energies on the single purpose of learning.

For four years Jackson did little else but study. He pored over his books at night by the light of the coal fire in his room until, a classmate said, he literally burned the lessons in his brain. They remained there. Jackson never forgot anything.

For four years Jackson did little else but study. He pored over his books at night by the light of the coal fire in his room until, a classmate said, he literally burned the lessons in his brain. They remained there. Jackson never forgot anything.

He made few friends, took no part in extracurricular activities, attained no cadet rank. He allowed himself solitary walks, and he was a faithful correspondent with his sister, Laura, back in Virginia. Those were the only “diversions” Jackson allowed himself to have. Resolution, patience, and constant study overcame all the handicaps that Jackson had faced. In the graduating class of 1846, he ranked seventeenth among fifty-nine seniors. Professors and cadets alike were unanimous in their opinion that had the curriculum lasted one more year, the orphan boy from the mountains would have been number one in his class.

At West Point, Jackson began jotting down in a small notebook one-line statements of life that he encountered here and there. What became the most famous of those quotations was also a testimonial to his four years at the academy: “You may be what ever you will resolve to be.”

War with Mexico was under way when Jackson entered the U.S. Army as a lieutenant in the 3d Artillery Regiment. At a time when the average man was five feet, seven inches tall and weighed 135 pounds, Jackson stood a full six feet and carried 175 pounds. He had an extended forehead, a sharp nose, unusually large hands and feet, and a surprisingly high-pitched voice. They physical feature that attracted instant attention were pale blue eyes that stared at everything with deep intensity.

Jackson’s battery was in reserve for the first six months after arriving in Mexico. The young lieutenant despaired of ever knowing the emotions of battle. Then, in March 1847, he saw his first action at Vera Cruz; thereafter, he was in the thick of the fighting at Contreras and Chapultepec. Within seven months, Jackson gained three brevet promotions for gallantry under fire. None of his classmates achieved as much, and no American officer received more citations for valor.

For the next two years, major Jackson performed uneventful duties at various army posts in New York. It was at the first of these assignments - Fort Hamilton - that his interest in religion emerged to the forefront. A reader of the Bible since his teenage years, Jackson now pursued a search for a religious home. He received baptism at an Episcopal church near Fort Hamilton, and he attended different services at various churches. None fulfilled his spiritual needs.

For the next two years, major Jackson performed uneventful duties at various army posts in New York. It was at the first of these assignments - Fort Hamilton - that his interest in religion emerged to the forefront. A reader of the Bible since his teenage years, Jackson now pursued a search for a religious home. He received baptism at an Episcopal church near Fort Hamilton, and he attended different services at various churches. None fulfilled his spiritual needs.

Although still an artillery officer, Jackson was also an assistant quartermaster at most of the posts to which he was sent. His most frequent duties were courts-martial. Such appointments took him to a number of military installations in New York and Pennsylvania. In his spare time, Jackson preferred reading. history was his favorite subject, Napoleon his favorite figure. Jackson also maintained a steady correspondence with his beloved sister, Laura. By then she had married and was living in Beverly in northwestern Virginia. For the next ten years, Jackson would make periodic visits to Beverly. He was very close to Laura, and he exhibited a growing affection for her small son, Thomas Jackson Arnold.

Concerns over health became a near obsession with Jackson. Stomach disorders and weak eyesight were the chief disorders, but Jackson was convinced at one time or other that every one of his organs was malfunctioning to some degree. He attributed his troubles as punishment from God for his sins. Jackson, like so many of his contemporaries, treated himself with a wide variety of medications. He also sought relief from several New York physicians.

The result of all the dosages, ministrations, and exercises was a twofold regimen that Jackson followed. To curb the pangs of dyspepsia, he ate only those things he did not like - and in small quantities. his strict diet actually brought an improvement over that ailment. To aid in combating all of his other physical problems, Jackson became an ardent devotee of hydrotherapy. He regularly visited spas in the summertime and became convinced that two or three weeks in such heavy water was quite beneficial.

In December 1850, Jackson’s artillery company transferred to duty at Fort Meade in the remote interior of Florida. The isolation and the boredom of that assignment, in addition to Jackson’s growing devotion to the word of God, were all instrumental in a bitter disagreement between Jackson and his superior, Major William H. French. Each soon filed formal accusations of misconduct against the other. At least one court-martial seemed imminent.

Such proceedings never occurred, because Jackson left the army. In the midst of the explosive situation, he received an offer to joint he faculty of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Located at Lexington in the upper (southern) end of the Shenandoah Valley, the academy, barely 12 years old, was small and somewhat unproven. Yet it offered Jackson a new life, a change of scenery, and an opportunity to return to western Virginia. he arrived in Lexington in late summer 1851 and entered a new world as a college professor.

Jackson spent a fourth of his life at VMI. While his name and that of the Institute are permanently intertwined, it was not because of performance in the section room. Unfamiliar with the subject matter he was to teach (Natural and Experimental Philosophy), and equally unfamiliar with teaching young boys, Jackson struggled for years to be effective in the classroom. He was forced to study as he taught, because topics in the course such as magnetism, acoustics, astronomy, and physics were alien to him. Mastering the subject was bad enough; learning how to present it was even more difficult. Jackson, a stickler for discipline, expected the same from students. Indifferent to opinions, he also lacked warmth and humor. Poor eyesight led him to memorize his lectures the day before he delivered them. Class presentation was a high-pitched monotone. If questioned on a point by a student, he was unable to respond with a different approach. Jackson could only repeat verbatim what he had just said. Finally, he never seemed to realize that he was dealing with immature boys, not soldiers accustomed to receiving orders.

Students initially took an instant dislike to him. Cadets referred to him as “Tom Fool,” “Old Blue Light,” “Hell and Thunder,” “crazy as damnation,” “the worst teacher that God has ever made,” and similar derogations. They played pranks on Jackson and scoffed with frustration because he never seemed aware of anything out of the ordinary.

“The Major” brought much of this on himself because of a number of eccentricities that he regularly exhibited. Without warning, he sometimes would thrust his arm into the air and make several, violent pumping motions with it - to create better blood circulation, he explained. On occasion, Jackson would forget to eat; he was known to wear winter clothing in the summer and vice versa; he walked with exaggerated strides, never looking right or left. Always did he seem wrapped in an inner concentration which no one could pierce for any length of time. His reticence led him at times to stare at a blank wall for hours.

On the other hand, Jackson displayed a number of positive qualities. He was honest to a fault, a careful businessman, neatly dressed at all times, conscientious in everything he did, and pleasant in the confines of small, private gatherings. VMI cadets came to see good qualities in him both as a teacher and as a leader. The ridicule of freshmen evolved to respect by seniors.

Within three months after arriving in Lexington, Jackson found his religious home. He joined the Presbyterian faith and rapidly became one of the most devout Calvinists of his day. Jackson attended every service at the Lexington Presbyterian Church. (To the amusement of the congregation, he slept through every service. Yet he would sit bolt upright, his back never touching the pew. This was self-induced pain he inflicted for the sin of not being able to stay awake.)

Within three months after arriving in Lexington, Jackson found his religious home. He joined the Presbyterian faith and rapidly became one of the most devout Calvinists of his day. Jackson attended every service at the Lexington Presbyterian Church. (To the amusement of the congregation, he slept through every service. Yet he would sit bolt upright, his back never touching the pew. This was self-induced pain he inflicted for the sin of not being able to stay awake.)

Jackson’s major contributions to the Lexington church was threefold. He organized a young men’s Sunday school class that still exists; he established a Sunday afternoon Bible class for slaves of all ages in the area; and he was appointed one of three deacons in the church.

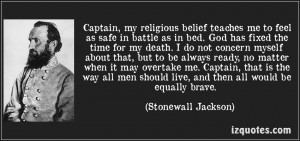

So faithfully did Jackson honor the Sabbath that he would not read or talk of secular matters on the Lord’s Day. Jackson found solace in prayer, which he offered throughout his waking hours, and strength in faith, because he knew that God was always there as a friend and helper.

His favorite scripture was Romans 8:28: “And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose.” His favorite hymn was “Amazing Grace,” but he could not explain why. He was completely tone-deaf. Most of all, Jackson bore his faith as if it were the sole staff of life. “Never have I known a holier man,” his best friend remarked. “Never have I seen a human being as thoroughly governed by duty. He lived only to please God; his daily life was a daily offering up of himself.”

In 1853, at age twenty-nine, Jackson fell in love for the first time in his life. Elinor Junkin was the daughter of a Presbyterian clergyman. Their marriage was joyful, faithful, and tragically short. Elinor died in childbirth fourteen months after the marriage. The son she was bearing also perished. Only Jackson’s faith sustained him in the tragedy. That same faith led quickly to a second tragedy.

Jackson and “Ellie’s” favorite sister Margaret gravitated to one another in their common grief. They came to enjoy one another’s company with growing ardor. Friendship ripened into love. however, by the tenets of the Presbyterian Church of that era, a person’s in-laws were his family. His sister-in-law, “Maggie,” thus in the eyes of the Church was his sister. Marriage was impossible. Once again Jackson endured pangs of sorrow and emptiness.

Within a year, he found a second wife. Anna Morrison also was a Presbyterian minister’s daughter. She and Jackson had known each other casually for several years. The VMI professor waged a courtship with all the fervor of a military operation. Thomas and Anna married in July 1857. This second marriage lasted for the remainder of Jackson’s life. To Anna he opened his heart in complete trust and gentle tenderness. However, their first child, a daughter, died shortly after birth.

Within a year, he found a second wife. Anna Morrison also was a Presbyterian minister’s daughter. She and Jackson had known each other casually for several years. The VMI professor waged a courtship with all the fervor of a military operation. Thomas and Anna married in July 1857. This second marriage lasted for the remainder of Jackson’s life. To Anna he opened his heart in complete trust and gentle tenderness. However, their first child, a daughter, died shortly after birth.

The Jackson’s had just settled into the only home he ever owned when, in the autumn of 1859, rumblings of disunion came closer and grew louder. Abolitionist John Brown led a bloody raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. A Marine detachment from Washington quickly crushed the uprising. In December, Jackson led part of the VMI corps of cadets to Charles Town to serve as a gallows guard for the public hanging of Brown.

Basically apolitical in nature, Jackson watched the growing national crisis from two perspectives. He considered the United States as established by the Constitution of 1787 to be a gift of God; conversely, any attempts to change the nature or language of that union Jackson regarded as heresy. Second, Virginia was his birthright. A federal government in Washington, D.C., took care of “housekeeping chores” such as delivering the mail. It had no business interfering with the affairs of the Old Dominion, which had existed for 180 years before a nation came into being.

The increasing unrest worried Jackson. In January 1860, he wrote to an aunt, “I think we have great reason for alarm, but my trust is in God; and I cannot think that he will permit the madness of men to interfere so materially with the Christian labors of this country.”

Jackson believed in the right of secession but not in its practice to adjust national wrongs. Yet when Virginia left the Union, he promptly did the same. On 20 April 1861, he departed Lexington with a contingent of cadets who were to serve as drillmasters for the thousands of recruits flocking to Richmond. Jackson would never see his adopted hometown again. It had been fourteen years since he had last experienced combat. Yet Jackson swept into war with a cool professionalism that reflected devotion to duty and confidence in himself.

None of that was obvious in his appearance. For the first year of the war, he wore the threadbare blue coat of a VMI faculty member, a battered kepi cap that seemed to rest on the bridge of his nose, and enormous boots that reached above his knees. While he never made mention in the war of his dyspeptic condition, weak eyesight and a hearing impairment (the result of an attack of neuralgia) were ever-present.

None of that was obvious in his appearance. For the first year of the war, he wore the threadbare blue coat of a VMI faculty member, a battered kepi cap that seemed to rest on the bridge of his nose, and enormous boots that reached above his knees. While he never made mention in the war of his dyspeptic condition, weak eyesight and a hearing impairment (the result of an attack of neuralgia) were ever-present.

Faith molded Jackson the soldier. He viewed the Civil War as a test of allegiance to God. For reasons man could not know, the Almighty had ordained that America undergo a trial by fire. The war, for the faithful, was a religious crusade, because God would surely bless the side that most obeyed His word.

Jackson viewed Christian faith and the Confederate cause as one and the same. While some generals aspired to be another Napoleon or Frederick the Great, Jackson’s inspirations were Joshua, Gideon, and David. To be worthy of New Testament love, Jackson believed, he must fight with Old Testament fury.

It took awhile for Jackson to put that faith into practice. After reaching Richmond in late April 1861, he received an appointment as colonel of infantry. His first assignment was to take command of gaudily dressed militia and inexperienced recruits gathering at Harper’s Ferry. The new post commander wasted no time in putting Harper’s Ferry into good military trim. Units accustomed to occasional parades underwent hours of daily drill; incompetent officers were sent home; all liquor in the town was poured into the streets; furloughs were nonexistent; men lived by a schedule; their camps were orderly and clean. Those who made honest mistakes were taught the correct way of doing things. Those who violated the rules knowingly received harsh punishment. Jackson expected his soldiers to share his rigid devotion to duty. He neither took leave nor granted it. (Throughout his Civil War career, he never spent a night away from army duty.)

An officer who returned to Harper’s Ferry a short time after Jackson took command exclaimed, “What a revolution three or four days had wrought! I could scarcely realize the change.”

The colonel ensured that Harper’s Ferry was properly fortified. With an artilleryman’s eye, Jackson saw at once that the key to defending Harper’s Ferry (and the Shenandoah Valley) was to place cannon atop commanding South Mountain across the Potomac River. Unfortunately, South Mountain was in Maryland, a neutral state. Jackson thought expediency more valuable than politics. The guns went into position. His action in violating neutrality for the sake of security was a factor in President Jefferson Davis’s dispatching General Joseph E. Johnston to replace Jackson as post commandant.

On 3 July 1861, Jackson received appointment as a brigadier general. His command was the 1st Virginia Brigade, five regiments raised in the Shenandoah Valley region. The unit’s first duty was in destroying sections of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Jackson did a thorough job; yet, he wrote his wife, “If the cost of the property could only have been expended in disseminating the gospel of the Prince of Peace.”

The new general and his troops acquired the most famous nickname in American military history in the Civil War’s first major battle. On 21 July 1861 on high ground overlooking Bull Run near Manassas Junction, Union and Confederate forces waged an all-day fight. Jackson carefully placed his regiments behind the brow of the highest eminence and waited. Soon, shattered Confederate forces retired to the base of the hill, with Federals in close pursuit confederate general Barnard Bee attempted to rally his broken units by pointing to the hilltop and shouting, “Look, men! There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

The new general and his troops acquired the most famous nickname in American military history in the Civil War’s first major battle. On 21 July 1861 on high ground overlooking Bull Run near Manassas Junction, Union and Confederate forces waged an all-day fight. Jackson carefully placed his regiments behind the brow of the highest eminence and waited. Soon, shattered Confederate forces retired to the base of the hill, with Federals in close pursuit confederate general Barnard Bee attempted to rally his broken units by pointing to the hilltop and shouting, “Look, men! There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

Jackson stood firm a while longer, then launched an attack as Federals advanced up Henry House Hill. A late-afternoon counterattack by fresh Southern troops sent Union soldiers staggering from the field. Jackson urged a pursuit of the Federals into Washington itself. yet authorities were content with the day’s success. The South had gained a stunning triumph and found a hero as well.

While many generals welcomed national attention, Jackson was uncomfortable in the spotlight. He did not particularly like the name “Stonewall.” It certainly proved to be a misnomer, for more often he would be the hammer rather than the anvil.

In the weeks that followed, the North mobilized for full-scale war while the South languished in a victor’s light. Jackson’s brigade lay quietly in encampment near Centreville until early November, when Jackson was promoted to major general and given command of the Shenandoah Valley district. The general established his headquarters at Winchester, collected a small force and, on 1 January 1862, began an expedition to clear Federals from river and railroad installations to the west.

This Romney campaign bordered on a disaster. Sleet, snow, and strong winds turned the march into a nightmare. Jackson ignored the weather and pushed forward. The farther he marched, the angrier he became at the heathen in his front. He railed against “the conduct of the reprobate Federal commanders who…have not only burned valuable mill property, but also many private houses… The number of dead animals lying along the roadside, where they had been shot by the enemy, exemplified the spirit of that part of the Northern army.”

This Romney campaign bordered on a disaster. Sleet, snow, and strong winds turned the march into a nightmare. Jackson ignored the weather and pushed forward. The farther he marched, the angrier he became at the heathen in his front. He railed against “the conduct of the reprobate Federal commanders who…have not only burned valuable mill property, but also many private houses… The number of dead animals lying along the roadside, where they had been shot by the enemy, exemplified the spirit of that part of the Northern army.”

The Confederates occupied the town of Romney and removed all Federal menaces from the area. A satisfied Jackson left General William Loring’s troops to occupy Romney and returned to Winchester with the rest of his command.

Loring immediately began complaining of isolation and hardships. The complains went directly to the War Department in Richmond. Secretary of War Judah Benjamin conferred with President Davis, then ordered Jackson to recall Loring’s men to Winchester. Jackson did so at once - and submitted his resignation from the army because of what he regarded as unwarranted interference with his authority. A storm of public outcry followed. Virginia governor John Letcher and other friends persuaded Jackson to remain in command. Loring was transferred elsewhere, and that was the last time Confederate authorities interfered with Jackson’s responsibilities.

This incident revealed much of Jackson the general. He was a man of unbending determination and self-confidence. The principal object of his life, he maintained, was the discharge of duty. While his men came to look on him with wonder and to refer to him affectionately as “Old Jack,” the general’s relations with his immediate subordinates was often stormy. He expected blind obedience because he gave it himself. He kept division and brigade commanders uninformed of movements because he viewed secrecy as one of the most valuable of military weapons. If friends did not know where he was going, Jackson once commented, enemies surely would not know either.

Such a policy left subordinates in the dark and created friction. Jackson ignored the unrest. He wanted his forces to be “an army of the living God,” he told his wife. Fighting for the Almighty, Jackson cared little about wounding the pride of his officers.

Jackson’s greatest achievement may have been the 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign. His responsibilities were twofold: to block any Union advance southward up the Shenandoah and to prevent Federal forces in that area from joining General George B. McClellan’s massive army then advancing slowly up the peninsula toward Richmond. The War Department had only to suggest an offensive. Jackson took it. One of the Confederacy’s better generals later declared that Jackson “suddenly broke loose…& not only astonished the weak minds of the enemy almost into paralysis, but dazzled the eyes of military men all over the world by an aggressive campaign which I believe to be unsurpassed in all military history for brilliancy & daring.”

On 23 March, at Kernstown just south of Winchester, Jackson attacked a Federal force preparing to depart the valley. Union brigades repelled the Confederate assaults, yet Jackson’s sudden activity caused Washington authorities to become uncertain of the situation in the Shenandoah.

Three Federal armies totaling 64,000 men were soon moving against Jackson from north, west, and east. With never more than 17,000 troops, Jackson unhesitatingly went after each. His principal weapons were secrecy, knowledge of the valley’s terrain, hard marches, and an uncanny ability to deliver heavy attacks at unexpected points, singleness of purpose with each thrust, and an abiding trust that God’s will was behind his efforts.

Late in April, Jackson momentarily disappeared from Federal view. he reappeared on 8 May by blocking Union general John C. Fremont’s advance at McDowell, west of the vital railroad town of Staunton. Jackson disappeared again. His “foot cavalry” (as the infantrymen proudly dubbed themselves) marched rapidly down the valley and, on 23 May, overpowered the Union garrison at Front Royal. The main Union army, under General Nathaniel P. Banks, desperately retired to Winchester. There, on 25 May, Jackson’s onslaught drove the enemy not only from Winchester but all the way across the Potomac River.

Late in April, Jackson momentarily disappeared from Federal view. he reappeared on 8 May by blocking Union general John C. Fremont’s advance at McDowell, west of the vital railroad town of Staunton. Jackson disappeared again. His “foot cavalry” (as the infantrymen proudly dubbed themselves) marched rapidly down the valley and, on 23 May, overpowered the Union garrison at Front Royal. The main Union army, under General Nathaniel P. Banks, desperately retired to Winchester. There, on 25 May, Jackson’s onslaught drove the enemy not only from Winchester but all the way across the Potomac River.

Officials in Washington hastily diverted troops toward the valley, motivated partly by apprehension for the Northern capital and partly by the desire to use converging columns to trap Jackson between Winchester and Harper’s Ferry. Union armies under Fremont and James Shields then sought to squeeze Jackson from east to west. The Confederate commander escaped the trap by an incredible march up the valley to a point east of Harrisonburg. Skillfully burning bridges to keep the two Union armies separated, Jackson patiently awaited their arrival. He struck Fremont on 8 June at Cross Keys and Shield on 9 June at Port Republic. Victories in both engagements cleared the valley of Union forces and ended the campaign.

The fruits of victory were many. Jackson had inflicted over 5,000 casualties and captured 9,000 small arms and tons of supplies, while losing only 3,100 troops (half of whom were captured). A dread of “Jackson in the rear” paralyzed thousands of Union soldiers who might have reinforced McClellan’s army at the gates of Richmond. A New York newspaper grudgingly stated, “He handles his army like a whip, making it crack in out of the way corners where you scarcely thought the lash would reach.”

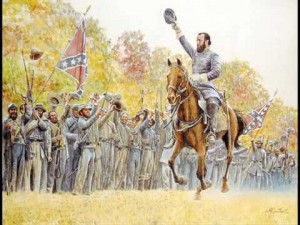

The test of a good general is morale inside the ranks. Jackson instilled high spirits among his soldiers. They viewed him as a military mastermind ordained by God to gain victory in battle. His skill implanted pride, unconquerable spirit, and elitism among the men. To be a member of “Jackson’s foot cavalry” set them a cut above all other soldiers.

The test of a good general is morale inside the ranks. Jackson instilled high spirits among his soldiers. They viewed him as a military mastermind ordained by God to gain victory in battle. His skill implanted pride, unconquerable spirit, and elitism among the men. To be a member of “Jackson’s foot cavalry” set them a cut above all other soldiers.

In addition, Jackson’s Valley campaign demonstrated that this strange, complex, seemingly lonely Presbyterian was one of those generals who performed best when the immediate situation was entirely in his control. While Jackson did not have to be completely in charge of everything, he wanted to be in command of the immediate task he was performing. Jackson could execute any assignment as long as he had complete control within his sphere. Ultimately self-reliant, never seeking advice (nor giving it, unless requested to do so), he earned his reputation and, in the process, created his legend.

Once asked his formula for success, Jackson looked back at his campaign in the Shenandoah and replied, “Always mystify, mislead and surprise the enemy, if possible; and when you strike and overcome him, never let up the pursuit so long as your men have the strength to follow; for an army routed, if hotly pursued, becomes panic-stricken, and can then be destroyed by half their number. The other rule is, never fight against heavy odds, if by any possible maneuvering you can hurl your own force on only a part, and that the weakest part, of your enemy and crush it. Such tactics will win every time, and a small army may thus destroy a large one in detail, and repeated victory will make it invincible.”

Once asked his formula for success, Jackson looked back at his campaign in the Shenandoah and replied, “Always mystify, mislead and surprise the enemy, if possible; and when you strike and overcome him, never let up the pursuit so long as your men have the strength to follow; for an army routed, if hotly pursued, becomes panic-stricken, and can then be destroyed by half their number. The other rule is, never fight against heavy odds, if by any possible maneuvering you can hurl your own force on only a part, and that the weakest part, of your enemy and crush it. Such tactics will win every time, and a small army may thus destroy a large one in detail, and repeated victory will make it invincible.”

Jackson gave the South a much-needed hero at a critical point in the war. yet no time existed after the Valley campaign to rest on laurels. General Robert E. Lee, the new commander of the South’s principal army, had watched the valley operations with fascination and pleasure. While others saw Jackson as a strange, rough-hewn leader, Lee saw in Jackson a kindred spirit who adhered to one of his own basic axioms: namely, that the inferior side must always be daring and willing to fight when the opportunity presented itself. Lee thereupon ordered Jackson to bring his forces to the Richmond front for a major counteroffensive against the Union Army of the Potomac.

The ensuing Seven Days’ campaign was a Confederate victory that brought instant fame to Lee. Yet Jackson’s performance was at least disappointing and at most controversial. The root of the problem with Jackson was utter fatigue. He had had no rest since the end of April, almost two months previously. Unfamiliarity with the terrain, poor communication with headquarters, and misunderstandings at high command were other factors present in this first major offensive by the Army of Northern Virginia.

Jackson was a delay behind schedule at the start. Inexplicable delays marked his movements; his famed “foot cavalry” crawled across country that was low, wet, and alien. Jackson never reached the opening engagement on 26 June at Mechanicsville. he was tardy the following day at the battle of Gaines’ Mill. On 30 June, Jackson seemed to become lethargic at White Oak Swamp. he failed to attack the high ground in his front or to lend any assistance to Confederates engaged in a severe fight a few miles away at Glendale. The brilliant tactician in the valley was glaringly absent in Lee’s first campaign.

Lee made no censure of Jackson. Perhaps the army commander saw the genius inside the shy, uncommunicative, humorless officer who would become his principal lieutenant for the next eleven months. Lee learned to give Jackson plenty of latitude in movements. His confidence was well founded. After the Seven Days, Jackson won new laurels with each succeeding engagement, for, like Lee, Jackson seized the initiative, divided enemy forces, and fought to destroy rather than merely to defeat.

In mid-July, Lee dispatched Jackson’s forces to central Virginia. A second Union army, under General John Pope, was advancing on Richmond from the northwest. Jackson struct the van of that army on 9 August at Cedar Mountain. In the fighting, Jackson personally rallied part of his command before Confederates sent beaten Federals reeling northward.

The Jackson of the Shenandoah Valley had replaced the Jackson of the Chickahominy. He again had become the Confederate man of the hour. A Georgia lieutenant spoke for the whole army when he wrote his wife, “O my dear, I wish you could just see him. See him before or after a battle as he passes the boys. They will run two hundred yards just to see him and yell like wildcats. he invariably, when they cheer him, uncovers his head and dashes along at rapid pace glancing his proud eagle eye from side to side. Then you aught to see him riding along when we are on the march, always calm and thoughtful with neat standing collar and old gray cap drawn down on his braud forehead.”

The Jackson of the Shenandoah Valley had replaced the Jackson of the Chickahominy. He again had become the Confederate man of the hour. A Georgia lieutenant spoke for the whole army when he wrote his wife, “O my dear, I wish you could just see him. See him before or after a battle as he passes the boys. They will run two hundred yards just to see him and yell like wildcats. he invariably, when they cheer him, uncovers his head and dashes along at rapid pace glancing his proud eagle eye from side to side. Then you aught to see him riding along when we are on the march, always calm and thoughtful with neat standing collar and old gray cap drawn down on his braud forehead.”

Pope promptly drew back to regroup. That bought time for Lee to secure Richmond against the hapless McClellan and reunite with Jackson. The full Confederate Army of Northern Virginia then advanced on Pope.

Jackson executed one of the brilliant flank marches known to Southerners and feared by Northerners. His men swung around Pope’s army, marched fifty-six miles in two days, and captured the main Federal supply depot miles in the rear of the Union forces. An angry Pope wheeled and came after Jackson. Fighting exploded on 28 August near the old Manassas battlefield. Combat continued for the next two days, at which point Lee’s half of the army assailed Pope’s undefended flank and sent another Union force on the road of defeat to Washington.

Lee then carried the war to the North with an invasion of Maryland. Jackson’s brigades overwhelmed the Union garrison at Harper’s Ferry in the largest capture of American soldiers until Corregidor in World War II. At Antietam on 17 September, the two opposing armies fought the bloodiest one-day battle in American annals. Jackson’s thin ranks manned Lee’s left and withstood heavy Union attacks throughout the morning. This defense reaffirmed Jackson’s nickname “Stonewall.” Lee held of McClellan skillfully but was forced to retire to Virginia for lack of resources.

Army reorganization came in the autumn, and with it a final promotion for Jackson. Lee wished to divided the Army of Northern Virginia into two corps. Each commander would hold the rank of lieutenant general. James Longstreet, the senior division commander, was a natural choice for one of the slots. Jackson was Lee’s most dependable general and the logical second recommendation. “I have only to intimate to him what I wish done,” Lee said, “and he promptly obeys my wishes.” Lee stated to President Davis, “He is true, honest, and brave; has a single eye to the good of the service and spares no exertion to accomplish his object.” The appointments were duly made.

Army reorganization came in the autumn, and with it a final promotion for Jackson. Lee wished to divided the Army of Northern Virginia into two corps. Each commander would hold the rank of lieutenant general. James Longstreet, the senior division commander, was a natural choice for one of the slots. Jackson was Lee’s most dependable general and the logical second recommendation. “I have only to intimate to him what I wish done,” Lee said, “and he promptly obeys my wishes.” Lee stated to President Davis, “He is true, honest, and brave; has a single eye to the good of the service and spares no exertion to accomplish his object.” The appointments were duly made.

Lee, with Longstreet’s half of the army, took a defensive position around Fredericksburg Jackson’s corps was left to guard the Shenandoah Valley

“Old Jack” spent the next weeks polishing his corps, reshuffling officers replenishing supplies and personally ensuring that religious services, Bibles, and tracts were available in all encampments A widening disagreement with General A.P. Hill who led the largest division under Jackson, overshadowed much of this period. However, Jackson’s spirits received an exhilarating boost with the news late in November that his wife had given birth to a daughter. Both mother and child were healthy. an uncharacteristic impatience then consumed Jackson. He longed to see his wife and to give love to a child of his own.

Before that could happen, the Army of the Potomac made another move toward Richmond. Lee and Jackson were waiting on high ground at Fredericksburg. The 13 December battle was Lee’s easiest victory.

By then, the aura and legend of Jackson were firmly established. He was the army’s aggressive general - the leader with an unquenchable fire for battle - the principal lieutenant who gained victory with unbroken regularity. His piety had become infectious enough to convince the soldiers that their cause was truly righteous. Everyone in the army talked about the time a mother hesitantly walked up to the mounted general and asked him to bless her 18-month old son. Jackson cuddled the baby in his arms and, while soldiers stood in silence with hats removed, put his face against the child’s and silently prayed.

That Jackson was also shy, private, almost reclusive, inserted a certain mysteriousness that only added to his image of invincibility.

Even his small, plain horse, “Little Sorrel,” became part of the apparition. A staff officer observed that Jackson’s “old sorrel is not more martial in appearance than his master, and the men say it takes a half dozen bomb shells to wake either of them up to their full capacity, but when once aroused there is no stopping either of them until the enemy has retreated.”

Even his small, plain horse, “Little Sorrel,” became part of the apparition. A staff officer observed that Jackson’s “old sorrel is not more martial in appearance than his master, and the men say it takes a half dozen bomb shells to wake either of them up to their full capacity, but when once aroused there is no stopping either of them until the enemy has retreated.”

Four months of winter inactivity followed the battle of Fredericksburg. Jackson used much of the period seeking to enkindle a deeper religious spirit among his men and in overseeing the preparation of his official battle reports. His formal summations are easily recognizable by their references to “the blessings of Almighty God” and “an all-wise Providence.” Jackson took no credit for victory. “Unto His holy name be the praise,” he insisted. He considered himself but God’s instrument in a crusade to purify America. That is why, at the height of one of his greatest military successes, Jackson turned to an aide and exclaimed joyfully: “He who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind!”

In late April 1863, Anna Jackson visited Jackson with their five-month-old child. Jackson was never happier than during those few days. The visit ended abruptly with news that the Union army again was on the offensive. Lee dispatched Jackson ten miles westward into the wooded jungle of the Wilderness. Jackson blunted the Federal advance near a crossroads known as Chancellorsville. Lee arrived on the scene, the two generals conferred, and Jackson embarked quickly on another flanking movement. This time he led 28,000 men on a twelve-mile march around the unprotected right flank of the Federal army.

Late in the afternoon of 2 May, Jackson struck. Once Federal corps all but fell apart in the face of Jackson’s onslaught; the Union line bent at ninety degrees as Jackson’s men drove the Federals for almost two miles. Darkness, weariness, and the confusion of the Wilderness stopped the advance.

Jackson was not content with what had been accomplished. He saw this moment as possibly the war’s climax. A night attack would surely rout the enemy and might bring the war to an end. Toward that end, Jackson rode from his lines and made a personal reconnaissance of the Union position. He was returning through the woods to his lines when one of his brigades mistook the general and his staff for Union cavalry. Confederates delivered a point-blank volley into the horsemen.

Jackson was not content with what had been accomplished. He saw this moment as possibly the war’s climax. A night attack would surely rout the enemy and might bring the war to an end. Toward that end, Jackson rode from his lines and made a personal reconnaissance of the Union position. He was returning through the woods to his lines when one of his brigades mistook the general and his staff for Union cavalry. Confederates delivered a point-blank volley into the horsemen.

Three bullets struck Jackson. While two made flesh wounds, the third shattered the bone in his left arm below the shoulder.

Amputation of the limb followed five hours alter at a field hospital. For safety reasons, Lee ordered Jackson removed to the railhead at Guiney Station. The wounded commander endured the bumpy, 27-mile wagon ride without complaint. Yet pneumonia rapidly developed. Jackson had always expressed the hope that he might be blessed to die on the Sabbath. Around 3:15 P.M. on Sunday, 10 May, he emerged from a terminal coma long enough to say: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

Amputation of the limb followed five hours alter at a field hospital. For safety reasons, Lee ordered Jackson removed to the railhead at Guiney Station. The wounded commander endured the bumpy, 27-mile wagon ride without complaint. Yet pneumonia rapidly developed. Jackson had always expressed the hope that he might be blessed to die on the Sabbath. Around 3:15 P.M. on Sunday, 10 May, he emerged from a terminal coma long enough to say: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The gifts of a supreme military leader were united in Jackson: imagination, speed, boldness, determination. To start before dawn, to march hour after hour, to pray long and hard, to fight with the relentless fury of a crusader, to look after his soldiers with the protective air of a stern father - these were part of Jackson’s makeup. He was harsh, because he hated weakness. He demanded so much of his men because he demanded so much of himself. He could insist on the impossible, for he was confident that with aggressive leadership and God’s blessing, the impossible could be accomplished.

A military genius fighting for the Lord must die to be defeated. Jackson’s death was the greatest personal loss suffered by the Confederate States. An estimated 25,000 people filed by his coffin in the rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol. Many Federal commanders refused for weeks to believe that Jackson was dead and not making another secret flanking movement. In contrast, the idea dawned on more than one Southerner that with Jackson’s passing, God was preparing the Confederacy for defeat.

A military genius fighting for the Lord must die to be defeated. Jackson’s death was the greatest personal loss suffered by the Confederate States. An estimated 25,000 people filed by his coffin in the rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol. Many Federal commanders refused for weeks to believe that Jackson was dead and not making another secret flanking movement. In contrast, the idea dawned on more than one Southerner that with Jackson’s passing, God was preparing the Confederacy for defeat.

Today the general is buried beneath his statue, which is the centerpiece of the Stonewall Jackson Cemetery at Lexington, Virginia.

- James I. Robertson, Jr.

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1058-1065]

For further reading:

[amazon_link id=”0393310868″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Farwell, Byron. Stonewall: A Biography of General Thomas J. Jackson (1993)[/amazon_link]

[amazon_link id=”0028646851″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Robertson, James. Stonewall Jackson. (1997)[/amazon_link]

[amazon_link id=”1581824858″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Robertson, James. Stonewall Jackson’s Book of Maxims. (2005)[/amazon_link]

[amazon_link id=”0306803186″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Henderson, G.F.R. Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War. (1988)[/amazon_link]