A brick tavern and family residence at the intersection of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road, Chancellorsville lent its name to one of the most important battles of the Civil War. Situated at the strategic intersection of five roads in the heavily wooded region north of Fredericksburg, Virginia, Chancellorsville evolved as one of Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s greatest triumphs.

A brick tavern and family residence at the intersection of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road, Chancellorsville lent its name to one of the most important battles of the Civil War. Situated at the strategic intersection of five roads in the heavily wooded region north of Fredericksburg, Virginia, Chancellorsville evolved as one of Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s greatest triumphs.

Since assuming command of the Army of the Potomac in January 1863, Union Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker focused his efforts on rebuilding his army after the previous December’s debacle at Fredericksburg. His army of 130,000 shouldered the finest weapons, wore the best uniforms, and ate the highest quality rations the United States could supply. His army included over 11,000 cavalry in a newly organized corps and 496 modern, rifled artillery pieces. With new equipment and daily drilling, Hooker considered the Army of the Potomac the finest army in the world. He also created an efficient intelligence service and integrated a tactical cover and deception operation into his plans to dislodge Lee from the trenches at Fredericksburg.

Through an adroit use of spies, line crossers, Confederate deserters, Union sympathizers, and intercepted Confederate semaphore messages, Hooker learned of the Confederate weakness around Fredericksburg. He received numerous reports of how thin Lee’s line was along the Rappahannock River. Frequent updates from the Confederate side of the river allowed Hooker to formulate a plan that initially deceived Lee and allowed the Union general to steal a march around the Confederate left flank. Hooker, unlike most Union generals in similar circumstances, also possessed a remarkably accurate estimate of Confederate troop strength before undertaking the campaign.

Across the Rappahannock, spread along the river’s edge for almost twenty-five miles, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia numbered about 60,000 effectives. Just off of a hard winter, Lee’s men resembled scarecrows more than soldiers. Tattered remnants of uniforms covered their malnourished frames and many lacked adequate footgear. They subsisted on a few ounces of cornmeal and bacon a day, the bacon rancid as often as not.

The gaunt Confederate horses and mules suffered from lack of fodder as well. A single rail line ran to the rear of the Confederate line at Fredericksburg and proved insufficient to supply Lee’s army. As a result he sent over 400 artillery horses to winter pasture farther south. Due to supply shortages and to counter a Federal threat to southeast Virginia, Lee had dispatched Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps to Suffolk, Virginia, thus depriving himself of his largest corps.

Hooker’s well-conceived strategy consisted of three major maneuvers. First, he would send his cavalry, commanded by Major General George Stoneman, far upriver with the double mission of drawing Lee’s cavalry screen away from the Confederate left flank and then raiding deep into Virginia to disrupt Lee’s supply line from Richmond. Second, he directed Major General John Sedgwick, with I and VI Corps, to deploy across from Fredericksburg and by strong demonstrations to divert Lee’s attention from the main Union attack. If Lee weakened his line, Sedgwick was to cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg to become the left wing of a double envelopment, crushing Lee’s retreating army. Major General Daniel Sickles’s III Corps would remain on Stafford Heights across from Fredericksburg to command the city with its long-range artillery. Third, Hooker planned to march upriver with Major Generals George G. Meade’s V, Oliver O. Howard’s XI, and Henry W. Slocum’s XII Corps. This force would rapidly cross the Rappahannock and crash down on Lee’s unprotected left flank. Hooker believed that whether Lee chose to remain and fight or retreat toward Richmond, Hooker could destroy the Army of Northern Virginia with his superior force.

Hooker’s well-conceived strategy consisted of three major maneuvers. First, he would send his cavalry, commanded by Major General George Stoneman, far upriver with the double mission of drawing Lee’s cavalry screen away from the Confederate left flank and then raiding deep into Virginia to disrupt Lee’s supply line from Richmond. Second, he directed Major General John Sedgwick, with I and VI Corps, to deploy across from Fredericksburg and by strong demonstrations to divert Lee’s attention from the main Union attack. If Lee weakened his line, Sedgwick was to cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg to become the left wing of a double envelopment, crushing Lee’s retreating army. Major General Daniel Sickles’s III Corps would remain on Stafford Heights across from Fredericksburg to command the city with its long-range artillery. Third, Hooker planned to march upriver with Major Generals George G. Meade’s V, Oliver O. Howard’s XI, and Henry W. Slocum’s XII Corps. This force would rapidly cross the Rappahannock and crash down on Lee’s unprotected left flank. Hooker believed that whether Lee chose to remain and fight or retreat toward Richmond, Hooker could destroy the Army of Northern Virginia with his superior force.

During mid-April Hooker set his plan in motion. He directed both cavalry and infantry demonstrations at all the major crossing sites in the vicinity of Fredericksburg. Lee believed that Hooker’s main thrust would come from the north. Yet with all the Union activity, he could not afford to redeploy his troops until he was sure of the main point of attack. Hooker had further convoluted the situation with false messages indicating Stoneman’s ultimate objective was the Shenandoah Valley. in all, his deceptions allowed Hooker to steal a march on Lee, something seldom, if ever, accomplished by Union generals. In fact, Hooker’s turning movement on Lee is arguably the greatest intelligence coup of the Civil War.

On 28 April Stoneman’s cavalry, hampered by inclement weather and muddy roads, finally initiated the campaign by crossing the Rappahannock and riding behind Lee’s lines. Hooker’s plan, however, began to unravel when Major General J.E.B. Stuart countered Stoneman’s raid with a small detachment of Confederate cavalry. Discerning that Stoneman’s purported thrust toward the valley was a ruse, Stuart rapidly realigned his horsemen along the river to screen Lee’s left flank. Stoneman’s harried command would ride through the Virginia woods for a week without accomplishing either the diversion of Confederate cavalry or the disruption of Lee’s railroad to the south.

On 29 April, Hooker pushed through Stuart’s cavalry screen at Kelly’s Ford north of Fredericksburg and then moved across the Rapidan River at Germanna and Ely’s Fords. While Hooker’s troops fought their way through Stuart’s small but slashing cavalry attacks and the almost impenetrable wilderness around Chancellorsville, Sedgwick threw two pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River in front of Jackson’s positions south of Fredericksburg. Both Lee and Jackson wanted to destroy one of the Union wings, but they disagreed about which one to attack. Lee decided to wait for the situation to develop further before committing himself to a pitched battle. He did, nonetheless, order Major General Richard Anderson to move his division toward Chancellorsville to confront any Yankee advance toward Fredericksburg.

On 30 April, when Hooker unaccountably halted his advance and consolidated his position, he lost the initiative and allowed Lee time to maneuver against him. In part, Hooker’s hesitation and his fading confidence resulted from his advance elements meeting stronger resistance than he had expected. Actually, he could have easily broken the thin Confederate line and advanced on both the Orange Turnpike and Plank Road. Historians still debate whether Hooker was drunk during the campaign. Known for his high consumption of alcohol, Hooker supposedly swore off liquor for the campaign, but some contemporary evidence indicated that he returned to the bottle for liquid courage when confronted by the determined Confederates.

When Stuart’s patrols and prisoners confirmed the large Federal force advancing from the north, Lee realized that the main attack was at Chancellorsville and Sedgwick’s river crossing was only a diversion. Lee immediately ordered Major General Jubal Early, with less than 10,000 effectives, to defend Fredericksburg from the trenches along Marye’s Heights. Lee would shift most of his army to meet Hooker’s advance. from Early’s left, Lee immediately sent two brigades from Major General Lafayette McLaws’s division to support Anderson near Zion Church Ridge east of Chancellorsville. Lee then directed Jackson to withdraw his men from their defensive line and move toward Chancellorsville. He also ordered Stuart to ascertain the size and locations of the Union force struggling through the underbrush around Chancellorsville.

Early on the morning of 1 May, Jackson donned a new uniform and led his corps to engage the Yankees east of Chancellorsville. When he arrived at the Confederate lines about 8 A.M., he promptly organized an attack with its axis of advance westward along both the Orange Turnpike and Plank Road. About 11:30 A.M. the Confederate skirmishers encountered the Union advance guard plodding east on the same roads. Without adequate cavalry support, the surprised Federal brigades grudgingly gave way to the advancing Rebel infantrymen. Lee soon arrived on the battlefield and assumed command from Jackson.

Utilizing an unfinished railroad bed graded through the thickets, Lee’s infantry turned the Union right and forced Hooker to bend his southern flank almost 90 degrees to meet the threat. By sundown, stiffening Federal resistance halted Lee’s advance through the darkening woods. Even though Sickles’s and Darius Couch’s corps had crossed the Rappahannock to reinforce him, Hooker unaccountably - and against his corps commanders’ advice - ordered his men to return to their positions of the previous night.

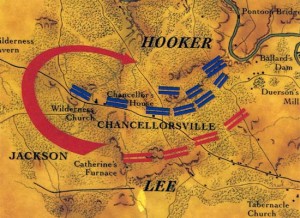

Seeking an opening for a morning attack, lee dispatched several of his staff officers to evaluate the Federal line, while he and Jackson sat at a campfire awaiting a report from Stuart. Upon their return, members of Lee’s staff adjudged the Union defenses too formidable for a frontal assault. Stuart and a local Confederate sympathizer, Charles C. Welford, on the other hand, arrived with much more decisive intelligence. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry had discovered Hooker’s unprotected right flank dangling in the wilderness, and Welford offered to lead the Confederates around Catherine’s Furnace and westward along little-known forest trails to exploit the situation. Lee had discovered Hooker’s weakness.

With this information Jackson, with Lee’s concurrence, formulated a plan that ignored most of the basic principles of war. His audacious plan called for Lee to hold Hooker in place with only 15,000 troops, while Jackson looped to the west with approximately 30,000 soldiers to attack the unprotected Union flank.

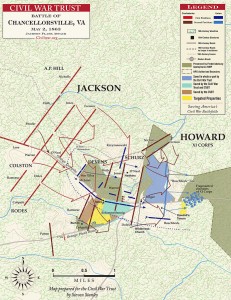

At 4 A.M. on 2 May, Lee held a final conference with Jackson and then ordered the day’s operations to commence. Jackson led the division of Robert Rodes, R.E. Colston, A.P. Hill, J.J. Archer, E.L. Thomas, and finally his artillery on a twelve-mile circuitous march through the heat of the day. To cover Jackson’s movements, Lee committed both Anderson’s and McLaw’s divisions in lines of skirmishers to make Hooker think it was a major assault. When one of Sickles’s divisions, situated on the high ground of Hazel Grove about one mile south of Chancellorsville, reported Confederate troops moving south near Catherine’s Furnace, Hooker thought it was evidence of Lee retreating. Oliver O. Howard, deployed on the Union right, reported that he had also seen this maneuver, but he was preparing for an attack from the west. Howard was counting on the tangled wilderness and only 700 men to defend his right flank. Unconcerned, Hooker turned his attention to Lee’s bothersome attacks east of the Chancellorsville crossroads. To put more pressure on what he mistakenly thought to be a retreating army, he ordered Sedgwick to attack the Confederate positions at Fredericksburg.

At 4 A.M. on 2 May, Lee held a final conference with Jackson and then ordered the day’s operations to commence. Jackson led the division of Robert Rodes, R.E. Colston, A.P. Hill, J.J. Archer, E.L. Thomas, and finally his artillery on a twelve-mile circuitous march through the heat of the day. To cover Jackson’s movements, Lee committed both Anderson’s and McLaw’s divisions in lines of skirmishers to make Hooker think it was a major assault. When one of Sickles’s divisions, situated on the high ground of Hazel Grove about one mile south of Chancellorsville, reported Confederate troops moving south near Catherine’s Furnace, Hooker thought it was evidence of Lee retreating. Oliver O. Howard, deployed on the Union right, reported that he had also seen this maneuver, but he was preparing for an attack from the west. Howard was counting on the tangled wilderness and only 700 men to defend his right flank. Unconcerned, Hooker turned his attention to Lee’s bothersome attacks east of the Chancellorsville crossroads. To put more pressure on what he mistakenly thought to be a retreating army, he ordered Sedgwick to attack the Confederate positions at Fredericksburg.

Jackson’s advance units did not arrive on a high wooded ridge west of Howard’s XI Corps until midafternoon. Jackson’s assault was delayed by his desire to gain the best position on the Federal right flank. As his brigades arrived Jackson arrayed them in an attack formation almost two miles long. In the fading daylight, Jackson quietly ordered his division commanders to commence their attacks.

As Howard’s men prepared their supper, a hoard of screaming Confederate infantrymen burst from the woods and routed the astonished Yankees. Jackson’s men irresistibly surged forward for over two miles before gathering darkness, loss of unit cohesion in the woods, and increasing Federal resistance finally halted their advance. When Jackson returned from a personal reconnaissance ahead of his disjointed units about 9 P.M., troops from the 18th North Carolina Infantry mistook his part in the darkness for Union cavalry and fired on it. Several of his staff fell wounded, and Jackson was hit in three places. Early the next day surgeons amputated his shattered left arm. He began a normal recovery but developed pneumonia and died on 10 May. Lee and the Confederacy lost one of their most aggressive generals, a loss that would be sorely felt at Gettysburg two months later.

Stuart assumed temporary command of Jackson’s corps after Jackson and his senior infantry officers fell wounded. During the night, Stuart prepared to resume the attack and drive on Chancellorsville. Confederate artillery officers identified the high ground at Hazel Grove as key to the battle, and Stuart planned to seize it at dawn. Hooker abandoned this decisive terrain before Stuart ordered his men forward, however, and Rebel artillerymen rushed to occupy the commanding terrain. Desperate fighting in the woods between Hazel Grove and Chancellorsville exacted more casualties on 3 May than had Jackson’s flank attack.

Concentrated Confederate cannon fire from Hazel Grove added to Union casualties and disorder. A shell struck the column on which Hooker was leaning at Chancellor’s Tavern and further addled the already disconcerted general. After a shot of brandy, hooker ordered a general withdrawal to the north. With his separated command linked together, Lee rode triumphantly to Chancellorsville Cross Roads among his cheering men.

The situation at Fredericksburg, however, demanded Lee’s immediate attention. Sedgwick, after three bloody assaults, had broken through Early’s positions at Marye’s Heights and the Federals were advancing on Lee’s rear. The Confederate commander quickly disengaged McLaws’s Division and ordered him east to meet Sedgwick. McLaws failed to react with alacrity, but General Willcox’s men halted the Union troops at Salem Church, four miles west of Fredericksburg. Lee arrived on the morning of 4 May to coordinate an attack that regained Marye’s Heights and forced Sedgwick to retire across the Rappahannock that night.

On 5-6 May, Hooker, against most of his subordinates’ advice, abandoned his line north of Chancellorsville and retreated across the Rappahannock. At any point during the campaign either of Hooker’s wings outnumbered their opponents and could have achieved his primary goal of driving Lee back toward Richmond if Hooker had followed his original plan. Yet Hooker’s vaunted intelligence operation broke down at the crucial moment. The absence of Stoneman’s cavalry meant that Hooker was deprived of intelligence about Confederate strength and positions; with such information he may well have won the battle.

Lee suffered about 13,000 casualties to Hooker’s 18,000. yet the most portentous casualty was Stonewall Jackson, whose death of 10 May required that Lee reorganize the Army of Northern Virginia. While the spectacular victory at Chancellorsville presented Lee with an opportunity to invade the North, it would not be the same army that did so. He and his men would carry and effusive confidence into battle at Gettysburg. There awaited the grim discovery that they were not invincible.

- Stanley S. McGowen

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. [amazon_link id=”039304758X” target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History[/amazon_link]. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 392-398]

Civil War Trust’s plans to save the Chancellorsville battlefield from development.

For additional reading:

[amazon_link id=”0395901367″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Fishel, Edwin C. The Secret War for the Union [/amazon_link](1996).

[amazon_link id=”0679728317″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Furgurson, Ernest B. Chancellorsville, 1863: The Souls of the Brave (1992)[/amazon_link].

[amazon_link id=”0807859702″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Chancellorsville: The Battle and Its Aftermath (1996).[/amazon_link]

[amazon_link id=”0028646851″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson: the Man, the Soldier, the Legend (1997).[/amazon_link]

[amazon_link id=”039587744X” target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Sears, Stephen W. Chancellorsville (1996).[/amazon_link]