By Jeffrey S. Williams

Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force

Following the U.S.-Dakota War in August-September, 1862, Henry Hastings Sibley was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the United States Army on September 29, 1862, and placed in command of Major General John Pope’s Department of the Northwest, which was created earlier in the month after Pope’s recent defeat at Second Bull Run. Sibley created a five-officer military commission comprised of Colonel William Crooks, 6th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry; Lieutenant Colonel William R. Marshall, 7th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry; Captains Hiram P. Grant and Hiram S. Bailey of the 6th Minnesota; and Lieutenant Rollin C. Olin of the 3rd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry, to conduct trials of the Indians that he thought had participated in the U.S.-Dakota War. The commission began its proceedings on September 28.

The trials, which began at Camp Release, were moved to the Lower Sioux Agency on October 15, and brought up nearly four hundred Dakota Sioux warriors on various charges. The commission found 303 Indians guilty of various charges, though frequently a guilty charge was pronounced if there was an admission that the accused was present at a battle and fired his gun. They were sentenced to death by hanging.

Because of the rapid speed in which the trials were conducted, Bishop Henry Whipple urged President Lincoln to review the commission’s proceedings. During this time, the condemned warriors were transferred to a stockade in the town of Mankato to await their fate. The 1,658 dependents of the prisoners were marched to Fort Snelling near St. Paul and placed in an internment camp. They were later transferred to a reservation at Crow Creek on the Missouri River, a barren land that caused many more to perish.

Bishop Whipple wrote a letter to Minnesota Senator Henry Rice, which he requested be delivered to the president. “We cannot hang men by the hundreds. Upon our own premises we have no right to do so,” the bishop wrote. “We claim that they are an independent nation & as such they are prisoners of war. The leaders must be punished but we cannot afford by any wanton cruelty to purchase the anger of God.”

As for the 303 deemed guilty, people were split over the matter. Quakers, clergy and even Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole cried out against execution, while the citizens of St. Paul sent a resolution to the president demanding that all of them be executed and that every Dakota Sioux Indian be banished from the state. Ultimately Lincoln himself on December 6, wrote the order to Brigadier General Sibley authorizing the execution of thirty-nine on the list who had been found guilty of murder and rape. Lincoln then gave a reprieve to Round Wind, who had been wrongly convicted because he was ten miles and on the opposite side of the river from where his original accusers claimed that he had been.

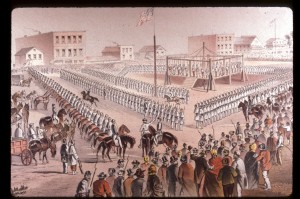

An artist’s depiction of the hanging of the Dakota 38 at Mankato, Minn., Dec. 26, 1862. This American tragedy was the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

A crowd of 1,400 soldiers and countless public spectators gathered in Mankato on Friday morning, December 26, 1862. They watched as the thirty-eight Dakota Sioux warriors climbed up to the platform on top of a scaffold. After shaking hands with each other and singing their death song, the condemned Indians clasped their hands as white hoods were pulled down over their heads. It was on the third tap from a lone drummer that gave William Duley, a survivor of the Lake Shetek massacre, the cue to pull the lever. When he did, the scaffold’s trap doors opened simultaneously. The largest mass execution in United States history had now occurred.

The executioners made one mistake, however. An Indian by the name of Chaska, the protector of Sarah Wakefield, was hanged instead of Chaskadon, who killed a pregnant woman and cut her child out of the womb. Reverend Stephen Riggs explained the mistake to Mrs. Wakefield two months later. “In regard to the mistake by which Chaska was hanged instead of another, I doubt whether I can satisfactorily explain it. We all felt a solemn responsibility and a fear that some mistake should occur,” Riggs wrote. “When the name Chaska was called in the prison on that fatal morning, your protector answered to it and walked out. I do not think anyone was to blame. We all regretted the mistake very much.” Over the years, efforts have been made to seek a presidential pardon for Chaska, but no pardon has been issued as of yet.

The Dakota Sioux people were punished severely after the execution. In addition to the establishment of the Crow Creek reservation, 326 Santee Sioux held at Mankato were transferred to Davenport, Iowa and confined for three years before being allowed to rejoin their families, who had been relocated to Nebraska in 1866. There were 120 Indians that died during their confinement in Iowa.

Nearly two thousand Winnebago Indians who did not take part in the U.S.-Dakota War, but lived near the town of Mankato, were forcibly removed to Dakota Territory.

On July 3, 1863, the same day that the Battle of Gettysburg reached its climax, Chief Little Crow and his son, Wowinape, returned to Minnesota and were picking berries at the Nathan Lamson farm near Hutchinson. Lamson fired two shots and killed Little Crow. Wowinape escaped and found his mother’s family in a reservation in the Dakota Territory. Little Crow’s body was scalped and dismembered.

Brigadier General Henry Hastings Sibley pursued the remnants of Little Crow’s warriors through Dakota Territory in 1863 and Brigadier General Alfred Sully continued that campaign in 1864. The battles between the United States and the Dakota escalated into the Plains Indian Wars and didn’t end until the Massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in December 1890.

Jacob Nix, the former Commandant of New Ulm, believes he knows why these events occurred. “Here in Minnesota the desire to gain wealth played an important role in bringing about the scenes of horror which took place in the last half of the month of August 1862. No one can deny that the greed of one of the government officials at that time had a great deal of responsibility for the terrible outbreak of the Sioux Indians in the Upper Mississippi Valley,” he wrote in 1887. “In fact, the same person who was possessed of only one thought, to squeeze a maximum of dollars out of the Indians, bears sole blame for the horrible fate of many brave settlers.” He placed the blame for the entire U.S.-Dakota War at the feet of Alexander Ramsey.

I had never heard the background to the battle at Wounded Knee. Thank you for a history lesson.

Very good article, I am glad to see someone telling the truth behind what really happened to the Native Americans because of greedy settlers in our country.