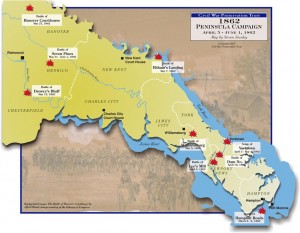

In the aftermath of Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston’s evacuation of Yorktown and his army’s retirement up the Virginia peninsula toward Richmond, the Army of the Potomac under George B. McClellan began a slow but steady pursuit. Although tempered by a defeat of federal gunboats below Drewry’s Bluff, the movement up the peninsula to the outskirts of the city created fear and consternation in Richmond. The situation appeared to be going from bad to worse as word came into Richmond that Irvin McDowell’s First Corps, now essentially an army numbering more than 30,000 was preparing to move toward Fredericksburg 50 miles north of the Confederate capital. The unified commands of McDowell and McClellan would number approximately 135,000 - double Johnston’s strength. Responding to orders, the commander of the Army of the Potomac positioned his troops in such a way as to maintain pressure on the Confederate capital from the east while at the same time facilitating a juncture with the First Corps as it moved southward from Fredericksburg. This meant that the Federal army would be forced to straddle the Chickahominy River - a waterway originating north of Richmond and flowing southeastward to the James.

In the aftermath of Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston’s evacuation of Yorktown and his army’s retirement up the Virginia peninsula toward Richmond, the Army of the Potomac under George B. McClellan began a slow but steady pursuit. Although tempered by a defeat of federal gunboats below Drewry’s Bluff, the movement up the peninsula to the outskirts of the city created fear and consternation in Richmond. The situation appeared to be going from bad to worse as word came into Richmond that Irvin McDowell’s First Corps, now essentially an army numbering more than 30,000 was preparing to move toward Fredericksburg 50 miles north of the Confederate capital. The unified commands of McDowell and McClellan would number approximately 135,000 - double Johnston’s strength. Responding to orders, the commander of the Army of the Potomac positioned his troops in such a way as to maintain pressure on the Confederate capital from the east while at the same time facilitating a juncture with the First Corps as it moved southward from Fredericksburg. This meant that the Federal army would be forced to straddle the Chickahominy River - a waterway originating north of Richmond and flowing southeastward to the James.

The proximity of the Army of the Potomac to Richmond led President Davis and Robert E. Lee, who essentially served as Davis’s military advisor, to meet with Johnston to discuss the general’s plans for defeating McClellan. While remaining secure behind Richmond’s defenses, Johnston advocated flexibility to react quickly to any mistake or opportunity presented by his federal counterpart. In an effort to keep his options open and to limit risks, Johnston avoided making a commitment to a fixed plan.

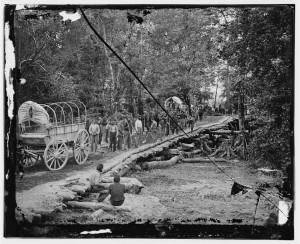

The opportunity Johnston was waiting for materialized at the end of the month. After rebuilding Bottom’s Bridge (one of the bridges across the Chickahominy destroyed by retreating Confederates), two federal corps commanded by Generals Erasmus D. Keyes and Samuel P. Heintzelman moved south across the river. Remaining to the north were three corps commanded by Generals Edwin Sumner, William Franklin, and Fitz John Porter. Efforts were underway to construct or rebuild eleven bridges between Bottom’s Bridge and Mechanicsville to facilitate a speedy reunion of the army when necessary. Thus, by 25 May the Chickahominy physically divided the Army of the Potomac into two “wings.”

Johnston, recognizing the opportunity to strike McClellan while his army was divided, determined to attack one or both of the wings. Johnston began to develop his plan after further consolidating his forces by moving Major General Benjamin Huger from Petersburg to Drewry’s Bluff and advising Brigadier Generals Lawrence O’Bryan Branch at Gordonsville and Joseph Reid Anderson near Fredericksburg to shift their troops closer to Richmond. He now had 75,000 men available, the largest army ever assembled in the Confederacy to that date. His initial concept was for an assault against the extreme right of the federal army north of the Chickahominy in conjunction with a strike against the right flank of the two corps south of the river. His decision to move against the federal right was based on the urgency created by the belief that McDowell was on his way to link up with McClellan This presumption was enhanced on 27 May by an engagement fifteen miles north of Richmond at Hanover Court House in which Fitz John Porter’s ifth Corps defeated 4,000 Confederates under Branch. This action appeared to be in preparation for the arrival of McDowell. A federal deafeat along the Chickahominy would prevent such a union by driving McClellan back away from Richmond and freeing Johnston to turn on McDowell.

Johnston, recognizing the opportunity to strike McClellan while his army was divided, determined to attack one or both of the wings. Johnston began to develop his plan after further consolidating his forces by moving Major General Benjamin Huger from Petersburg to Drewry’s Bluff and advising Brigadier Generals Lawrence O’Bryan Branch at Gordonsville and Joseph Reid Anderson near Fredericksburg to shift their troops closer to Richmond. He now had 75,000 men available, the largest army ever assembled in the Confederacy to that date. His initial concept was for an assault against the extreme right of the federal army north of the Chickahominy in conjunction with a strike against the right flank of the two corps south of the river. His decision to move against the federal right was based on the urgency created by the belief that McDowell was on his way to link up with McClellan This presumption was enhanced on 27 May by an engagement fifteen miles north of Richmond at Hanover Court House in which Fitz John Porter’s ifth Corps defeated 4,000 Confederates under Branch. This action appeared to be in preparation for the arrival of McDowell. A federal deafeat along the Chickahominy would prevent such a union by driving McClellan back away from Richmond and freeing Johnston to turn on McDowell.

Johnston planned to attack on 29 May, but information coming from Confederate Cavalry under Brigadier General J.E.B. Stuart the previous evening indicated a change in the federal plans. McDowell was no longer heading south - the First corps was being withdrawn to support Federal operations against “Stonewall” Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. Now, with an entirely different situation confronting him, the Confederate commander no longer needed to attack to forestall the unification of Federal forces. Yet, circumstances were still favorable for a tactical offensive Johnston saw an opportunity to eliminate the weaker of McClellan’s two wings and then turn on the three corps north of the river.

The 5th New Hampshire Infantry constructs their “Grapevine Bridge,” which did not survive the May 1862 flood of the Chickahominy River in Virginia. This photo, however, is the only surviving photograph of either bridge known to exist. (Library of Congress image)

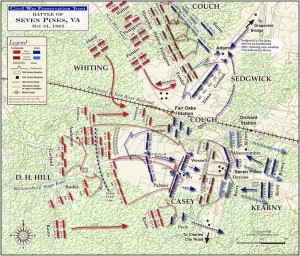

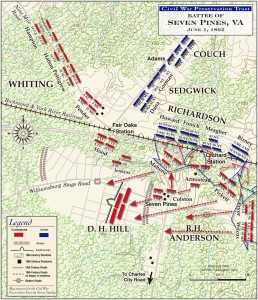

The 31,500 men south of the river under Keyes and Heintzelman had advanced west of their river crossing and were dispersed in four lines. One division of Keyes’s corps was in line one mile west of Seven Pines, a road junction six miles east of Richmond on the Williamsburg Road. Keyes’s other division stretched from Seven Pines north to Fair Oaks Station on the Richmond & York River Railroad. Heintzelman’s two divisions were located to the rear of Keyes, one at Savage Station, two miles east of Fair Oaks Station, and one near Bottom’s Bridge. McClellan did not anticipate a Confederate offensive.

Johnston’s battle plan for 31 May directed the divisions of Generals James Longstreet and Daniel Harvey Hill to assault Keyes’s right and center while Huger’s division, moving from the southwest, turned the enemy’s left flank. General Gustavus W. Smith was ordered first to engage troops that might attempt to cross the Chickahominy to aid Keyes and Heintzelman, and then (if no federal reinforcement arrived) to support Longstreet’s attack on the Federal right. All troops were to advance toward the enemy using the existing road network which conveniently converged at Keyes’s position. In the early morning attack, the latter division would be smashed first, then Heintzelman, moving up to support Keyes, would meet the same fate. These instructions were given orally to Longstreet who was given tactical command of the operation based on his performance at Williamsburg and his seniority in rank to Hill and Huger.

While Johnston’s plan was tactically sound, he erred in issuing his orders orally and not by informing all his division commander’s that Longstreet was in tactical command. The result was confusion and delay. In addition, the weather added its own impedance. The day before the battle rain turned the roads into quadmires.

The 31 May battle at Seven Pines did not go well at all for Johnston. Longstreet did not take his assigned route to the attack. Instead he moved his 14,000-man division farther south to the Williamsburg Road currently occupied by D.H. Hill’s division. This shift ultimately weakened the Confederate assault against the Federal right and created a nightmare in coordination when Huger’s men prepared to enter this same road to reach their assigned point of attack. Huger, initially unaware that Longstreet was in tactical command, lost the argument that he should have priority over the road.

Johnston became increasingly concerned when the expected sounds of battle did not reach his headquarters during the early morning. His anxiety grew when Brigadier General William Henry Chase Whiting, in command of Smith’s division, could not locate Longstreet’s which his was to follow into position. After a delay of over six hours, the assault finally commenced at a little after 2:00. Only six of the intended thirteen brigades were in position when the battle began. Huger’s three brigades and three brigades from Longstreet’s division were mired in White Oak Swamp south of Seven Pines. One brigade was held back to protect the Confederate left. The assault, although bearing little resemblance to Johnston’s original plan, was nevertheless gallant and determined. Longstreet sent a message to Johnston notifying his commander that the battle had been underway for several hours and requesting support for his left flank in the form of an attack upon the Federal right and rear. Longstreet anticipated that such a blow could terminate the battle before nightfall.

Johnston ordered General Smith’s division to advance toward Seven Pines to aid Longstreet. The commanding general then left his headquarters and rode to the front to oversee the assault. However, instead of striking a blow against a weakened Keyes near Seven Pines, Johnston found himself facing fresh troops at Fair Oaks. Fire coming from this newly arrived Federal force struck the left flank of Smith’s division as it moved past Fair Oaks. Caught by surprise, the Confederates were brought into a general engagement north of Seven Pines and were unable to aid Longstreet in his efforts against Keyes.

By 6:30, Johnston was convinced that the contest would have to be renewed the following day. He rode forward toward his frontline positions, issued orders for a cease-fire, and instructed his men to sleep on their arms. The commanding general was exposed to sporadic enemy fire during this process and around 7:00 was shot in the right shoulder. Immediately following this wound, Johnston was hit in the breast by a shell fragment which knocked him, unconscious, off his horse. The general was carried to a less exposed position and awaited an ambulance to remove him from the field.

By 6:30, Johnston was convinced that the contest would have to be renewed the following day. He rode forward toward his frontline positions, issued orders for a cease-fire, and instructed his men to sleep on their arms. The commanding general was exposed to sporadic enemy fire during this process and around 7:00 was shot in the right shoulder. Immediately following this wound, Johnston was hit in the breast by a shell fragment which knocked him, unconscious, off his horse. The general was carried to a less exposed position and awaited an ambulance to remove him from the field.

President Davis and General Lee, who had been at Johnston’s headquarters earlier in the day, rode up on what must have been a shocking scene. The command responsibility fell briefly to General Smith. On 1 June, Smith renewed the attack with a series of poorly orchestrated assaults. By late morning the Confederates recognized the folly of continuing the battle and began a general withdrawal from the field. That same day, President Davis issued orders for Robert E. Lee to assume command of the Confederate army outside Richmond. Confederate losses for the two-day battle were 6,134 men killed, wounded, or missing, while the Army of the Potomac suffered 5,031 total casualties.

- Alan C. Downs

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 673-676]

For further reading:

Gallagher, Gary W. The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula and the Seven Days. (2008).

Dougherty, Kevin The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis (2010).

Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (2001).

Schroeder, Rudolph J. Seven Days before Richmond: McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign of 1862 and it’s Aftermath (2009).

Visit the Civil War Trust’s page on the Battle of Fair Oaks/Seven Pines by clicking here.

Also, The Bridge that Saved an Army: The ‘Grapevine Bridge’ and the Battle of Fair Oaks.