By Jeffrey S. Williams

Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force

Following the Siege of Yorktown, Battles of Williamsburg and West Point, along with the Union Navy’s failed assault against Drewry’s Bluff, the Federal forces of Major General George B. McClellan were making progress in their Spring 1862 campaign to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.

By May 23, the First Minnesota Volunteer Infantry was camped at Goodly Hole Creek on the north bank of the Chickahominy River in Hanover County, Virginia. They were approximately eight miles north of Richmond, so close they could even hear the church bells ringing from the distant city, while they performed their service as “pioneers.”

During the week, the Minnesotans, assigned to Gorman’s Brigade of Sedgwick’s Second Division of the Second Corps, were tasked with building one of four bridges across the Chickahominy in order for the Army of the Potomac to make a crossing to descend on Richmond. Their bridge was considered the “upper” bridge, with the Fifth New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, assigned to Howard’s Brigade of Richardson’s First Division of the Second Corps, leading the construction of a lower bridge a few miles away. There were three other bridges already built, plus a railroad bridge, all within 12 miles of their position. Two other bridges were constructed by different Corps further upstream.

Two companies of Minnesotans, Company B from Stillwater, under the command of Capt. Mark W. Downie, and Company D from Minneapolis, under the command of 2nd Lt. Christopher Heffelfinger, were tasked with constructing the upper bridge with two experienced engineers, most likely Maj. Daniel P. Woodbury and Lt. Col. Barton Alexander, supervising. Members of Company K were also called to assist.

“About 3 companys had to work in the watter waste deep all day. We built what has since been called Sumners upper Bridge or Sullys Bridge,” Cpl. Mathew Marvin of Company K recorded in his diary.

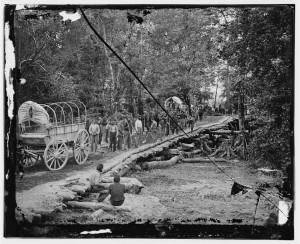

The 5th New Hampshire Infantry constructs their “Grapevine Bridge,” which did not survive the May 1862 flood of the Chickahominy River in Virginia. This photo, however, is the only surviving photograph of either bridge known to exist. (Library of Congress image)

James A. Wright of Company F described the construction process. “The whole structure was a simple one, and just such a one as I had seen built on the Cannon River when the first stage road was made to St. Paul. ‘Cribs’ – or pens, of logs were built at proper distances apart, to the desired height. On these cribs, long ‘stringers’ were laid; and on these, the flooring of the bridge. The logs of these cribs were notched together at the corners and were fastened with pins and withes, until the weight – as they were built up – forced them to the bottom. These cribs had to be held in position until they found a resting place in the mud,” he wrote.

Sgt. William Lochren of Company E recalled, “It was built of logs cut near the banks by the men, and was completed before sunset, excepting a part of the corduroy approach on the north side, which was constructed by another regiment on the following day. As grapevines, which grew plentifully on the banks, were used instead of withes about its construction, it was called ‘Grapevine Bridge.’” The use of grapevines instead of withes was suggested by Captain Downie.

The Chickahominy River rises into highlands to the northwest of Richmond, wraps around the city on the north and east sides, then empties into the James River several miles south. The bottom lands between the highlands and White Oak Swamp are only slightly elevated, which means that if the river rises by only a few feet, the area overflows into a large area making it spongy and not practical for cavalry and artillery to commence operations. The Corps was located in these bottom lands.

Chaplain Edward Neill vividly recalled the storm that hit on the night of May 30. “There were constant rains, and on Friday night, the thirtieth of May, the windows of the clouds were wide open, and torrents of water poured out. Lightnings, like zigzag arrows of fire, darted to the earth, followed by long rolls of thunder. The superstitious might have supposed that there was war in heaven.”

On the afternoon of May 31, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston realized that McClellan’s army was split, with three corps north of the river and two having crossed the river, and launched a surprise attack. Before the attack was launched, Thaddeus S.C. Lowe, from his post in the balloon Intrepid, observed that the Confederate army was moving into battle position. He relayed this information to McClellan, who ordered Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner’s Second Corps to cross to the south bank of the river.

Colonel Alexander, the engineer¸ saw how the rains from the night before created a flood situation and implored General Sumner not to cross the shaky bridge. Alexander wasn’t sure if the bridge would hold the weight of the infantry regiments and artillery batteries that needed to cross.

Sumner, who wasn’t about to disobey a direct order, stated, “I can, sir! I will, sir!”

Alexander implored upon him again to reconsider.

“Sir, I tell you I can cross. I am ordered!” He then proceeded to cross his Corps across the Chickahominy starting with Gorman’s brigade, with the First Minnesota as the lead regiment.

Colonel Alexander admitted that the general even had his doubts about the rickety bridge that was even with the waterline. “The possibility of crossing was doubted by all present, including General Sumner himself. As the solid column of infantry entered upon the bridge, it swayed to and fro to the angry flood below or the living freight above, settling down and grasping the solid stumps by which it was made secure as the line advanced. Once filled with men, however, it was safe until the Corps crossed; it then soon became impassable,” he said in the Atlantic Monthly in March 1864.

Chaplain Neill remembered the crossing. “As the bridge was approached it was seen to be surrounded by swift water. The soldiers waded up to their waists, reached it, and crossed. Then followed Kirby’s Battery, the drivers lashing their horses, the nozzles of the guns immersed, and as they plunged on the log bridge it trembled, undulated, and was ready to float away,” he wrote.

The regiment’s assistant surgeon, Dr. Daniel W. Hand remembered that “the logs would bob up and down under the horses’ feet in a startling manner.”

The fortunes of Richardson’s division weren’t as good. Only French’s brigade was able to cross the lower bridge, constructed by the Fifth New Hampshire, but only after great difficulty. It was constructed similar to the upper bridge, including the use of grapevines for suspension, but the swiftness of the current at that location made it unusable.

The First Minnesota’s “Grapevine Bridge” was durable enough to cross all three of Sedgwick’s brigades and two of Richardson’s brigades before it collapsed, making it the only one that was able to withstand the floodwaters of May 1862.

The Fifth New Hampshire veterans tried to assert that it was their bridge that withstood the flooding, and published that claim in 1912, which infuriated Wright.

“If the First Minnesota had performed no other service on the Peninsula but the building of this bridge, it would still be entitled to great praise for a good job well done, but it not only built the bridge, it led the way across it to the relief of the hard pressed left wing,” he added.

As a result of the reinforcements from the Second Corps, the Confederate offensive was halted. One bridge constructed by lumberjacks from Minnesota saved the day for McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign.

For further reading on the Battle of Fair Oaks, click here.

Pingback: Swamped | Encyclopedia Virginia: The Blog

Pingback: On this date in Civil War History: May 31-June 1, 1862 - The Battle of Fair Oaks/Seven Pines | This Week in the Civil War

amazing story… thank you.