By Darryl Sannes

Minnesota Civil War Commemoration Task Force

On May 5, 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac entered the abandoned Confederate entrenchments at Yorktown, Virginia. The first major confrontation in this campaign had been a success for the North, though it had taken way too long. What should have been accomplished in days, took an entire month.

On May 5, 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac entered the abandoned Confederate entrenchments at Yorktown, Virginia. The first major confrontation in this campaign had been a success for the North, though it had taken way too long. What should have been accomplished in days, took an entire month.

In the spring of 1862, Major General George McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, implemented his plan to approach the Confederate capital of Richmond from the south. His innovative strategy was to avoid the direct route from Washington to Richmond and outmaneuver the Confederates led by General Joseph Johnston. The plan called for an amphibious landing on the Virginia peninsula, separated by the James and York Rivers, and move quickly north toward Richmond, before Johnston could move his Army of Northern Virginia south to stop them. The Peninsula Campaign was the largest single campaign of the Civil War. In three weeks, 121,500 men, 14,592 animals, 1,224 wagons and ambulances, 44 artillery batteries and countless amounts of equipment had were moved to Fort Monroe on the southern end of the peninsula.

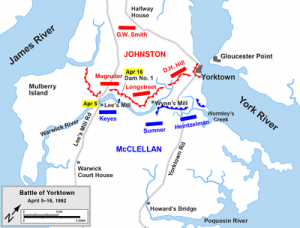

McClellan’s army moved quickly to the north until they ran into Confederate entrenchments near Yorktown, Virginia. Yorktown had been the site where 81 years before, Lord Cornwallis had surrendered to General George Washington in the final battle of the Revolutionary War. Rather than moving rapidly to attack and move the Confederates back, McClellan chose to entrench and to begin a siege of Yorktown. The defense of the Confederate line was given to Major General John B. Magruder, while Johnston attempted to organize the rest of the army spread out over eastern Virginia.

Thinking that he was vastly outnumbered in troop strength while bemoaning the fact that President Lincoln dispatched some of his troops under John Pope to defend Washington, McClellan settled in for a long siege. McClellan was building his reputation as a general who was always “preparing to fight” while struggling to “pull the trigger.”

The Union army dug in about a mile south of the Confederate entrenchments and the First Minnesota held a position in the middle of the line. The two armies had gone to ground and began the seldom deadly, and mostly dull, life of siege warfare. The daily routine for the soldiers of the First Minnesota involved building fortifications, picket duty, and clearing and building roads; while listening to the constant exchange of artillery fire. Soldiers of the First became adept at constructing corduroy roads, which were built by placing newly cut logs lengthwise, and used to move batteries into place along the Union siege line, through wooded and wet areas. In his book, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign, Stephen Sears writes, “The best at this road-making proved to be the 1st Minnesota regiment, whose skilled woodsmen could clear a mile of road and corduroy a quarter of it in a day.”

The most dangerous duty for the soldiers during the siege was when they were placed as advanced picket lines. Well within the firing range of the Confederate sharpshooters, they learned quickly to keep their heads down. In mid-April, after two weeks of the siege, members of Company K found themselves in a minor skirmish. While on advanced picket duty, they took some grape shot from the Confederate artillery. They returned fire, driving them back to their entrenchments. The soldiers of Company K yelled, goading them to come out and exchange a volley, but they stayed to ground.

Finally, in early May, after a full month of siege warfare, McClellan prepared for an attack. Still believing he was outnumbered, he gave into the impatience of President Lincoln and planned for an assault on the morning of May 5. With their good intelligence gathering, Johnston and the Army of Northern Virginia became aware of McClellan’s plan and withdrew from Yorktown overnight. The next morning the First Minnesota with the rest of the Army of the Potomac entered the abandoned Confederate earthworks to find equipment and supplies strewn about. The Confederates left in a hurry.

The Confederates were vastly outnumbered and could have been taken at any time. Initially there had been about 15,000 soldiers behind the earthworks, though that number grew to 57,000 during the month. It should have been no match to the 120,000 men that McClellan commanded. The month-long delay allowed Johnston to move his army into place and lessened McClellan’s ability to outmaneuver the Confederates. The Siege of Yorktown foreshadowed much of what was to come in the war. The Peninsula Campaign would continue.

Click here to read the letter for Lt. Col. Stephen Miller to Lt. Gov. Ignatius Donnelly about the skirmishes at West Point, the Siege of Yorktown and land mines, that was dated May 8, 1862