Both Union and Confederate troops sabotaged railroads to impede enemy supply and troop transport. The Andrew’s Raid, popularly known as the “Great Locomotive Chase,” was one of the best-known attempts at railroad destruction during the Civil War. The Civil War was the first U.S. war in which railroads were used. Because tracks linked major cities, control of the railroad provided a strategic advantage.

In the spring of 1862, the Confederate defense line stretched from Richmond, Virginia, to Corinth, Mississippi. General Joseph E. Johnston was at Richmond, relying on railroads to connect with forces in the Deep South that were commanded by General P.G.T. Beauregard The rail line between Richmond and Memphis, passing through east Tennessee, was the quickest route. From Memphis, supplies could be diverted to or received from such major centers as New Orleans, Mobile, Montgomery, Charleston, and Savannah. Union strategists realized that controlling the Tennessee railroad would hinder Confederate troops in Virginia. Brigadier General Ormsby M. Mitchel planned to move Union troops from western Tennessee to the eastern part of the state, expelling Confederates from Chattanooga. from there, he planned to launch an assault against Virginia and defeat the Confederacy. To achieve this, he wanted to damage the rail lines from Atlanta to Chattanooga.

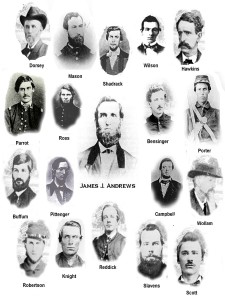

Previously, an effort to destroy the Western & Atlantic Railroad’s bridges in Georgia had failed because the operatives did not show up as planned in Atlanta. On 7 April 1862, Mitchel asked James J. Andrews, a furtive character with a mysterious past, to recruit volunteers for a second attempt. Andrews had admirably performed spying missions for General Don Carlos Buell and had also smuggled quinine to Union troops. Mitchel ordered Andrews to steal a train to burn railroad bridges, destroy tracks, and cut telegraph lines along the Georgia State Railroad south of Chattanooga. At the same time, Mitchel planned to secure Huntsville, Alabama, and move east to meet up with Andrews and his men behind Federal lines in Chattanooga. (The Andrew’s Raiders are sometimes also referred to as the Mitchel’s Raiders.) Twenty-two Ohio soldiers from General Joshua W. Sill’s brigade accepted Andrew’s invitation. Traveling from Shelbyville, Tennessee, wearing civilian clothes, they walked through rain and mud in small groups to Chattanooga where they boarded a southbound train. By midnight on 11 April, the raiders reached Marietta, Georgia, where they rendezvoused with Andrews. Several of the volunteers were delayed by the weather, and two had been impressed into the Confederate army. The next morning, they bought tickets to Big Shanty (Kennesaw), Georgia, twenty-five miles north of Atlanta. When they arrived, they discovered that a Confederate camp was located by the tracks, a fact that Andrews had been unaware of, and he told his men to proceed cautiously.

Previously, an effort to destroy the Western & Atlantic Railroad’s bridges in Georgia had failed because the operatives did not show up as planned in Atlanta. On 7 April 1862, Mitchel asked James J. Andrews, a furtive character with a mysterious past, to recruit volunteers for a second attempt. Andrews had admirably performed spying missions for General Don Carlos Buell and had also smuggled quinine to Union troops. Mitchel ordered Andrews to steal a train to burn railroad bridges, destroy tracks, and cut telegraph lines along the Georgia State Railroad south of Chattanooga. At the same time, Mitchel planned to secure Huntsville, Alabama, and move east to meet up with Andrews and his men behind Federal lines in Chattanooga. (The Andrew’s Raiders are sometimes also referred to as the Mitchel’s Raiders.) Twenty-two Ohio soldiers from General Joshua W. Sill’s brigade accepted Andrew’s invitation. Traveling from Shelbyville, Tennessee, wearing civilian clothes, they walked through rain and mud in small groups to Chattanooga where they boarded a southbound train. By midnight on 11 April, the raiders reached Marietta, Georgia, where they rendezvoused with Andrews. Several of the volunteers were delayed by the weather, and two had been impressed into the Confederate army. The next morning, they bought tickets to Big Shanty (Kennesaw), Georgia, twenty-five miles north of Atlanta. When they arrived, they discovered that a Confederate camp was located by the tracks, a fact that Andrews had been unaware of, and he told his men to proceed cautiously.

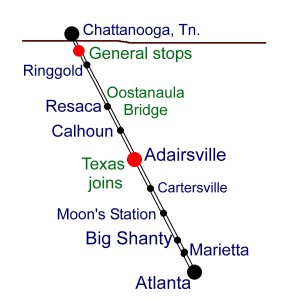

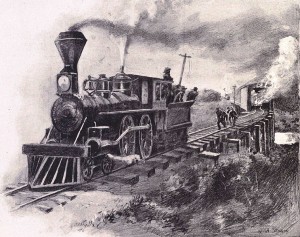

While the train’s crew and passengers ate breakfast at a restaurant, the Union raiders separated the steam locomotive named the General, the tender, and three boxcars from the train and opened the throttle to leave the station. A Confederate sentry observed the train thieves, but was unsure if they were railroad employees or saboteurs. When he realized were stealing the engine, he was unable to notify other stations because Big Shanty did not have a telegraph. Inside the restaurant, the General’s conductor, Captain William A. Fuller and crew heard the train and rushed outside to see the engine departing while Confederate soldiers fired rifles at it. Fuller, engineer Jeff Cain, and shop foreman Anthony Murphy began running after the General, and two miles up the track, they found a handcar. The handcar derailed at a spot where the raiders had broken the rails. Placing the handcar back on the tracks, the train crew reached Etowah, Georgia, where they found the engine Yonah sitting on a siding. The raiders had not stopped to disable the Yonah because they feared it would raise suspicions. While the train crew steamed up the Yonah, the raiders topped to cut telegraph wires at several places so that any pursuers could not warn stations up the tracks. Andrews had obtained a timetable for the railroad and put the General on a siding at Kingston, Georgia, so that a scheduled southbound express train could pass. However, two more trains arrived that were not listed on the timetable, and an anxious Andrews insisted that he be allowed to pass, stating that he had orders to deliver a trainload of gunpowder to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard When Andrews demanded to know the cause of the delay, the station agent told him that General Mitchel had captured Huntsville and Confederate train traffic had been diverted to the Georgia route.

While the train’s crew and passengers ate breakfast at a restaurant, the Union raiders separated the steam locomotive named the General, the tender, and three boxcars from the train and opened the throttle to leave the station. A Confederate sentry observed the train thieves, but was unsure if they were railroad employees or saboteurs. When he realized were stealing the engine, he was unable to notify other stations because Big Shanty did not have a telegraph. Inside the restaurant, the General’s conductor, Captain William A. Fuller and crew heard the train and rushed outside to see the engine departing while Confederate soldiers fired rifles at it. Fuller, engineer Jeff Cain, and shop foreman Anthony Murphy began running after the General, and two miles up the track, they found a handcar. The handcar derailed at a spot where the raiders had broken the rails. Placing the handcar back on the tracks, the train crew reached Etowah, Georgia, where they found the engine Yonah sitting on a siding. The raiders had not stopped to disable the Yonah because they feared it would raise suspicions. While the train crew steamed up the Yonah, the raiders topped to cut telegraph wires at several places so that any pursuers could not warn stations up the tracks. Andrews had obtained a timetable for the railroad and put the General on a siding at Kingston, Georgia, so that a scheduled southbound express train could pass. However, two more trains arrived that were not listed on the timetable, and an anxious Andrews insisted that he be allowed to pass, stating that he had orders to deliver a trainload of gunpowder to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard When Andrews demanded to know the cause of the delay, the station agent told him that General Mitchel had captured Huntsville and Confederate train traffic had been diverted to the Georgia route.

After sixty-five minutes of waiting, the raiders were permitted to continue. Five minutes later, Fuller and his men were stopped by the three southbound trains. They abandoned the Yonah on a siding and traveled to a junction two miles north of Kingston where they took the engine named William L. Smith, but were halted by the broken rails that the raiders had thrown on the tracks. Fuller and Murphy raced on foot, stopping the engine Texas at Adairsville and then pursuing the General in reverse. The raiders released two boxcars to block the Texas. When they tried to burn bridges, the rain-soaked wood refused to catch fire, and they left a boxcar aflame on one bridge. After pushing the boxcars onto a siding, the Texas began a pursuit that reached speeds of sixty miles per hour, with the pursuers catching glimpses of the General. Depleted of wood and water, the General lost steam two miles north of Ringgold, just south of the Tennessee border. The approximately ninety-mile chase ended with the raiders abandoning the General and running into the woods.

After sixty-five minutes of waiting, the raiders were permitted to continue. Five minutes later, Fuller and his men were stopped by the three southbound trains. They abandoned the Yonah on a siding and traveled to a junction two miles north of Kingston where they took the engine named William L. Smith, but were halted by the broken rails that the raiders had thrown on the tracks. Fuller and Murphy raced on foot, stopping the engine Texas at Adairsville and then pursuing the General in reverse. The raiders released two boxcars to block the Texas. When they tried to burn bridges, the rain-soaked wood refused to catch fire, and they left a boxcar aflame on one bridge. After pushing the boxcars onto a siding, the Texas began a pursuit that reached speeds of sixty miles per hour, with the pursuers catching glimpses of the General. Depleted of wood and water, the General lost steam two miles north of Ringgold, just south of the Tennessee border. The approximately ninety-mile chase ended with the raiders abandoning the General and running into the woods.

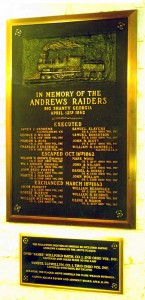

Search parties located and captured most of the raiders within days and placed them in jails at Chattanooga and Atlanta. Two raiders floated down the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers to the coast, and others who eluded capture headed north to rejoin their regiments. Andrews and seven men were tried as spies and hanged in Atlanta in June. If they had worn uniforms, they would have been considered prisoners of war. Six raiders were exchanged for Confederate prisoners and were awarded the U.S. Army’s first Medal of Honor in March 1863. The remaining raiders, except Andrews, later received Medals of Honor, including posthumous presentations.

Search parties located and captured most of the raiders within days and placed them in jails at Chattanooga and Atlanta. Two raiders floated down the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers to the coast, and others who eluded capture headed north to rejoin their regiments. Andrews and seven men were tried as spies and hanged in Atlanta in June. If they had worn uniforms, they would have been considered prisoners of war. Six raiders were exchanged for Confederate prisoners and were awarded the U.S. Army’s first Medal of Honor in March 1863. The remaining raiders, except Andrews, later received Medals of Honor, including posthumous presentations.

The surviving Andrew’s Raiders wrote articles and books about their adventures, attended anniversary celebrations of the raid, and were honored guests at Grand Army of the Republic conventions. The General was displayed at the 1888 national grand encampment in Columbus, Ohio. The Confederate pursuers joined the raiders to speak to audiences about the chase.

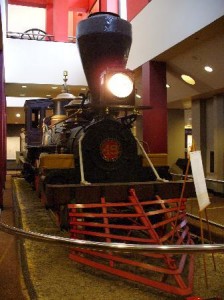

In May 1891, several raiders also attended dedication services for the Ohio monument at the National Cemetery in Chattanooga. Topped by a bronze replica of the General, the monument was placed next to the graves of the executed raiders. Historical markers were placed at significant Andrew’s Raid sites in Tennessee and Georgia. In April 1962, a steam engine reenacted the chase for the Civil War Centennial, and President John F. Kennedy hosted ceremonies at the White House for the raiders’ descendants. The General toured the United States before being housed at the Big Shanty Museum in Kennesaw (now known as the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History). The Texas was displayed in the lobby of the Atlanta Cyclorama & Civil War Museum at Grant Park. Embellished as a folk legend, the Andrews’s Riad was the subject of books and movies, including Walt Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase (1956)[amazon_link id=”B0000DZTNF” target=”_blank” locale=”US” container=”” container_class=”” ])[/amazon_link].

- Elizabeth D. Schafer

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 53-54]

For further reading:

Bonds, Russell S. Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor. (2008)

Cohen, Stan. The General and the Texas: A Pictoral History of the Andrews Raid, April 12, 1862. (1999)

Blue & Gray Magazine - July 1987 (Vol. 4, Issue 6): The Great Locomotive Chase.

“Andrews’ Raiders

- James J. Andrews, Kentucky, Leader of the Expedition. Hanged

- William. Knight, Co. E, 21st Ohio Volunteers. Escaped

- Wilson H. Brown, Co. F, 21st Ohio. Escaped

- Mark Wood, Co. C, 21st Ohio. Escaped

- Alfred Wilson, Co. C, 21st Ohio. Escaped

- John R. Porter, Co. G, 21st Ohio. Escaped

- Robert Buffum, Co. H, 21st Ohio. Exchanged

- William Bensinger, Co. G, 21st Ohio. Exchanged

- John Moorehead Scott, Co. F, 21st Ohio. Hanged

- Sargent E. A. Mason Co. K, 21st Ohio. Exchanged

- Daniel A. Dorsey, Co. H, 33rd Ohio. Escaped

- Martin J. Hawkins, Co. A, 33rd Ohio. Escaped

- John Whollan (Wollam), Co. C, 33rd Ohio. Escaped

- Jacob Parrot, Co. K, 33rd Ohio. Corporal Exchanged

- William Reddick, Co. B, 33rd Ohio. Exchanged

- Samuel Robertson Co. G, 33rd Ohio. Hanged

- Samuel Slavens, Co. D, 33rd Ohio. Hanged

- Corporal William Pittinger, Co. G, 2nd Ohio. Exchanged

- George Davenport Wilson, Co. B, 2nd Ohio. Hanged

- Marion Ross, Co. A, 2nd Ohio, Sergeant-Major of the Regiment. Hanged

- Philip Gephart “Perry” Shadrack, Co. K, 2nd Ohio. Hanged

- William Campbell of Kentucky. Hanged

Crew of the General

- William A. Fuller, Conductor

- E. Jefferson (Jeff) Cain, Engineer

- Anthony Murphy, Foreman of Machinery and Motive Power for the Western and Atlantic Railroad

Crew of the Texas

- Peter James Bracken, Engineer

- Henry Haney, Fireman

- Fleming Cox, Engineer - Mr. Cox was an engineer on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad who relieved Haney as fireman.

- Alonzo Martin - boarded in Calhoun. Unloaded tender car.

Others involved:

- Edward R. Henderson - Telegraph operator (messenger), Dalton

- Jackson Bond - worked at Moon’s Station. Continued on with the pursuers to Ringgold.

Pingback: The First Medals of Honor | PA Pundits - International