Fought in the early spring of 1862 on the west bank of the Tennessee River just north of the Mississippi state line, the battle of Shiloh was, up to that time, the biggest battle of American history. For two days in April, Confederates and Federals - 100,000 soldiers in all - waged a desperate struggle through the fields, forests, orchards, ravines, creeks and swampy areas near a steamboat docking point called Pittsburg Landing. Major Civil War commanders such as Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Don Carlos Buell, A.S. Johnston, P.G.T. Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, and Nathan Bedford Forrest participated.

The engagement played a significant role in the campaign for control of the Mississippi Valley. It also resented a terrible preview of all the other major battles of the war that were yet to come. For the first time in the conflict, men on both sides came to envision something of the true cost in suffering and death that victory would ultimately entail. People like General Grant, who had thought that perhaps one great battle would bring the war to a conclusion, would sense, after Shiloh, that such was not to be; that the war must go on, draining the nation of men, money, and resources, until either the Confederacy was finally smashed or the Union was divided.

The events that led up to Shiloh commenced in the winter of 1862. In early February, a Federal army-navy offensive, under command of Grant and Andrew H. Foote, penetrated the Confederate defensive perimeter across southern Kentucky. Driving south up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, they captured the supposed strongpoints protecting those vital waterways, respectively Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, located near the Tennessee-Kentucky border. The very heart of Tennessee was thereby laid open to the Union forces. The fall of the two forts began a series of Federal victories that left the Confederacy struggling to stave off disaster.

The Confederate defensive line across southern Kentucky, centered at Bowling Green, collapsed at once and the grayclads retreated from northern Tennessee to Alabama and Mississippi. A Union army under Don Carlos Buell advanced, virtually unopposed, into the capital of Tennessee, a major arsenal, transportation center, and supply depot. Suddenly, Nashville found itself the first Confederate state capital to fall to the blueclads.

The fall of Fort Henry opened the Tennessee River as an avenue of Union advance to the Alabama and Mississippi state lines. It enabled the Federals to immediately break one east-west railroad, the Memphis, Clarksville & Louisville, which crossed the Tennessee only seventeen miles south of Fort Henry. Three gunboats did the work of destroying the bridge. The gunboats then continued (south) up the Tennessee, knocking out other bridges and cutting telegraph lines, all the way to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Union forces under Major General Grant advanced south past Savannah, which Grant selected for his headquarters, to Pittsburg Landing, a site chosen by Sherman for the army’s encampments. There, only twenty miles northeast of Corinth, Mississippi, the Union force was ominously close to the Confederacy’s most important east-west railroad, the Memphis & Charleston line, which crossed the north-south Mobile & Ohio at the little Mississippi town.

If the Union army, designated the Army of the Tennessee, captured Corinth, not only would the federals control the railroad, but Memphis, outflanked by Union forces, probably would fall, opening several hundred miles of the Mississippi River to Federal forces. by late March, unit of command had been achieved for the blueclads in the West with Major General Henry W. Halleck directing the Department of the Mississippi. with both Grant’s and Buell’s armies under his control, Halleck then ordered Buell and his Army of the Ohio still in Nashville, to join up with Grant on the Tennessee River for an offensive against Corinth.

The Confederates, meanwhile, were gathering in force around Corinth. Coming from many places throughout the South - Mobile, Pensacola, New Orleans, Nashville, Memphis - they hoped to muster enough strength to stop the Union advance before Buell could reinforce Grant. The result of their effort was the battle of Pittsburg Landing, as the Union termed it, or the battle of Shiloh, as the Southerners called it. Shiloh has become the better known designation, after the Shiloh Methodist Church, located near the point where the fighting began.

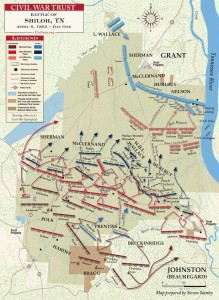

Shiloh - April 6, 1862 (Map courtesy of the Civil War Trust)

General Albert Sidney Johnston, considered by Jefferson Davis as perhaps the premier general of the Confederacy, commanded about 44,000 troops in his Army of Mississippi. Second in command was General P.G.T. Beauregard. On 3 April, the Confederates began marching out of Corinth, moving on two roads, roughly parallel, intending to surprise Grant’s 42,000 men with an attack before Buell’s 25,000 could reinforce him. The Confederate plan was to march from Corinth to Pittsburg Landing and be deployed in battle line by late morning of 4 April. Actually, the intended one-day advance consumed three days, as rain, a complex marching plan, rugged terrain (heavily wooded and cut by creeks, ravines, swampy areas, and confusing dirt roads), and inexperienced soldiers hindered the movement dramatically. Beauregard urged Johnston to call off the attack. he was convinced that the delays in marching and the noise made by the green Southerners (occasionally evening shooting at rabbits and deer) would have the Federals fully alerted and firmly entrenched. But Johnston refused to turn back. Ordering the attack for the early morning of Sunday, 6 April, the general is said to have dramatically announced something to the effect that on the following evening the army would water its horses in the Tennessee River.

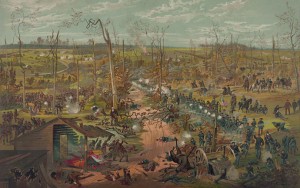

Shiloh Cyclorama. While the original work by French artist Theophile Poilpot was displayed only briefly in Chicago and Washington before being dismantled, this portion was used in advertisements for the McCormick Reaper Company into the 20th century. (Library of Congress)

Striking at dawn, the Confederate army achieved a complete strategic surprise. The first fighting occurred as the grayclad skirmishers engaged Federal patrols about three-fourths of a mile south of the Shiloh Church. Fighting a delaying action, the Union troops were compelled to fall back as the Rebel main body came on behind their skirmishers. But many Union soldiers, despite the heavy skirmishing occurring only a short distance away, remained unaware that the Rebels were upon them. Suddenly, screaming Confederates emerged from the woods to the south, and in some sectors, streamed directly into Union camps.

At first, a Confederate triumph seemed highly probably. The Yankee encampments lacked tactical formation, and inexperienced troops held the advance positions, the first to be struck by the Southern onslaught. Neither Grant, at his headquarters nine miles away, nor Sherman, the camp commander, had expected an attack. Grant had recently told the commander of Buell’s advance division that there would be no fight at Pittsburg Landing; he said the Federals would have to go to Corinth, where the Rebels were fortifying. Sherman, on 5 April, had written Grant, expressing his confidence that no attack would be made on the Union position at the landing. Confidence and offense had been the orders of the day for the two key men in the Union army. Thus the Confederates, in spite of their time-consuming and noise-making approach, enjoyed the elements of surprise and momentum as well as a slight numerical advantage. Union miscues added to the Southern advantage, as the Union division of Major General Lew Wallace never got into the battle on 6 April and some 5,000 Union soldiers (perhaps more) fled from the fight in panic.

But the Confederate attack, unfortunately for the Southerners, did not develop as General Johnston had originally planned. Apparently there was confusion (or disagreement) in the high command over whether to drive the Federals back to Pittsburg Landing or away from it. Compounding the confusion was an attack formation in which their corps advanced with one in front of another rather than side by side. Command control was sacrificed as regiments, brigades, and divisions became badly intermingled. All of this slowed the initial momentum that had given the Southerners an advantage at the beginning of the fight. Also, early in the afternoon, General Johnston suffered a leg wound and, in a short time, bled to death. General Sherman thought that a lull in the fighting followed the death of the Confederate commander, further sapping the energy of the Rebel attack. Possibly more important than any other factor, the “Hornet’s Nest,” as it was called by the Southerners, was a natural defensive position along a slightly eroded wagon trace that became a rallying point for Union troops, first those of General Benjamin Prentiss’s division, as they fell back toward the landing. Soon troops from several divisions joined Prentiss’s men in defending the position against repeated Confederate attacks.

But the Confederate attack, unfortunately for the Southerners, did not develop as General Johnston had originally planned. Apparently there was confusion (or disagreement) in the high command over whether to drive the Federals back to Pittsburg Landing or away from it. Compounding the confusion was an attack formation in which their corps advanced with one in front of another rather than side by side. Command control was sacrificed as regiments, brigades, and divisions became badly intermingled. All of this slowed the initial momentum that had given the Southerners an advantage at the beginning of the fight. Also, early in the afternoon, General Johnston suffered a leg wound and, in a short time, bled to death. General Sherman thought that a lull in the fighting followed the death of the Confederate commander, further sapping the energy of the Rebel attack. Possibly more important than any other factor, the “Hornet’s Nest,” as it was called by the Southerners, was a natural defensive position along a slightly eroded wagon trace that became a rallying point for Union troops, first those of General Benjamin Prentiss’s division, as they fell back toward the landing. Soon troops from several divisions joined Prentiss’s men in defending the position against repeated Confederate attacks.

Time and again the Confederates attempted to storm this Union strongpoint. They came across the open fields and they came through the timber. Federal major D.W. Reed, who fought in the Hornet’s Nest and was a careful student of the battle, said as many as twelve separate charges were made against the line. It was not until about 5:30 in the afternoon that the grayclads succeeded, finally, in reducing the Union position.

The fight at the Hornet’s Nest cost the Southerners too much time and too many men - it was while attempting to reduce the Hornet’s Nest that Johnston was killed - and drew their attention away from an opportunity earlier in the day, to break through the weak Federal left nearer the river. The Rebel focus on the Hornet’s Nest gave Grant, who hurried from Savannah at the sound of the battle, a sorely needed opportunity to establish a last line of defense at Pittsburg Landing.

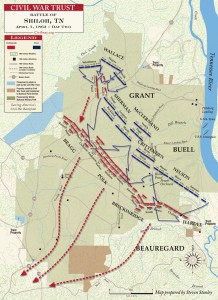

Beauregard took command after Johnston’s death and continued the assault until the Rebels, shortly before dark, held the entire battlefield except for the Yankee line covering the landing. Beauregard chose not to make an attack on the Federals at the landing, a decision that has been second-guessed by many. Probably the exhausted and disorganized Southerners, some of whom were out of ammunition, could not have overcome the Union line. That line, shortened and compacted, and supported by artillery, was also being reinforced by the first arrivals of Buell’s army. But Beauregard needed either to attack or withdraw because, during the night, Buell came up on the Federal left with thousands of reinforcements and

Lew Wallace arrived with his division from Crump’s Landing to take a position on the right side of the Union line. Thus the Federals could count an additional 25,000 men on 7 April. Although Beauregard did not know about these fresh enemy troops (indeed, he had false information that Buell was headed elsewhere), there is no evidence that he made any attempt to learn anything about the Federal situation. Like many Confederates, he apparently thought the Yankees were whipped.

Grant struck at dawn and drove the grayclads back across the battlefield and forced them to retreat to Corinth. Battle casualties approached 24,000; each side counted more than 1,700 dead and 8,000 wounded, with those missing accounting for the remainder. The killed and wounded at Bull Run, Wilson’s Creek, Fort Donelson, and Elkhorn Tavern, all put together, did not equal the killed and wounded at Shiloh, clearly making it the bloodiest battle of the war to that time. Moreover, the Union army had turned back a major Southern counteroffensive, maintaining its position on the flank of the line of the Mississippi River, and within a few miles of the strategic Memphis & Charleston Railroad that was soon to be in Federal hands. The battle opened the way to split the Confederacy along the Mississippi, which, in the long run, spelled defeat for the Confederacy.

- James L. McDonough

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1775-1780]

Click here to learn about the Civil War Trust’s effort to preserve 491 acres at Shiloh.

Click here to read Shiloh: From the Company Clerk’s Morning Report - 1st Minnesota Light Artillery.

Click here to read 1st Minnesota Light Artillery at Shiloh and Corinth.

Click here for the Union and Confederate Orders of Battle for Shiloh (coming soon).

Further reading:

Olney, Warren. Shiloh as seen by a private soldier with some reminiscences. (2010)

Cunningham, Edward. Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 (2009)

Daniel, Larry J. Shiloh: The Battle that changed the Civil War (1998)

McDonough, James L. Shiloh: In Hell Before Night (1977)

Pingback: This Week in the Civil War - April 2-8, 1862 (150 years ago) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Shiloh: From the Company Clerk's Morning Report - 1st MN Light Artillery | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: 1st Minnesota Light Artillery at Shiloh and Corinth | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: National Park Service Director Jarvis Addresses The Value and Importance Of Maintaining Civil War Sites | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: What are the ten costliest battles of the Civil War? Here’s your answer: | This Week in the Civil War