Located on the west bank of the Cumberland river two miles north of Dover, Tennessee, Fort Donelson was on a steep bluff overlooking a straight stretch of several miles of river. The fort itself was only about 15 acres, but its outer works extended over 100 acres. Four hundred log cabins within the fort served as barracks.

Fort Donelson had two river batteries cut into the slope of the ridge facing downriver. The lower battery contained a 10-inch Columbiad and nine 32-pounders. The upper battery had a 10-inch Columbiad and two 32-pounder corronades. The fort itself had eight additional guns. On 7 February, the day after the fall of nearby Fort Henry, Fort Donelson’s garrison numbered only about 6,000 men, including two brigades of infantry from Fort Henry.

Confederate Western theater commander General Albert S. Johnston now blundered. Although he decided to extract his garrisons in Kentucky and at Columbus, he reinforced Fort Donelson with 12,000 men to hold Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant’s troops until he could withdraw most of his eastern forces to Nashville. Johnston could have concentrated some 30,000 men at Fort Donelson, outnumbering Grant there two to one.

Johnston appointed Brigadier General John B. Floyd to command Fort Donelson. Floyd was at best incompetent; his second in command, Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow, was both ambitious and incompetent. Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner was the one capable senior Confederate officer at Fort Donelson.

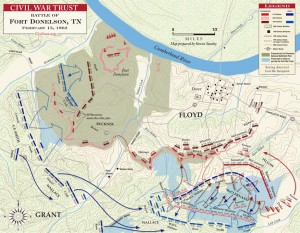

Bad weather imposed a delay, but on 12 February Grant moved from Fort Henry to Fort Donelson. At the same time, Union flag officer Andrew H. Foote sailed with his gunboats and Union troop transports, arriving near Fort Donelson on the night of the 13th. That day 15,000 unentrenched Union troops confronted 21,000 entrenched Confederates; but fortunately for Grant, Floyd made no effort to attack. In fact, Union troops initiated what little fighting occurred.

Shortly after noon on the 13th, despite Grant’s order not to bring on a general engagement, Brigadier General John A. McClernand ordered his men to capture a battery in the center of the Confederate line, but repeated Union assaults failed. Grant was displeased, but the action did serve to mask Union inferiority in numbers. That afternoon the weather changed dramatically from near summer to winter conditions; driving wind brough sleet and snow and suffering to both sides.

By the 14th the Confederates were completely invested, except along the Cumberland River above Dover, where the river had flooded the land. As Grant strengthened and extended his lines, the Confederate commanders decided to attempt to break out, but on the 14th Floyd countermanded the order on the insistence of Pillow, who thought it too late that day.

Grant planned to hold the Confederates within the fort from the land while the Union flotilla destroyed the water batteries. Shortly before 3:00 p.m. on the 14th, the Union flotilla attacked with four ironclads; two vulnerable timberclads formed a second division astern, beyond the range of Fort Donelson’s guns.

The Union ships closed to within 400 yards. The plunging fire hit the sloping Union armor at right angles, and in the exchange three of the four ironclads were disabled and drifted downstream The other vessels then withdrew. In the 90-minute engagement the flotilla had eleven men killed and forty-three wounded (including Foote). Although none of the gunboats were fatally damaged, from this point on the navy contributed little to the battle. In contrast, the fort was little damaged in the attack.

Union troop reinforcements continued to arrive. Before dawn on the 15th, Grant left his headquarters to meet with Foote at the latter’s request. Before leaving, Grant instructed his commanders not to initiate an engagement unless he ordered it. Grant assumed that he would be the one to begin any new fighting. The Confederate commanders knew their position was untenable, however. On the night of the 14th they agreed to attempt to break out along the west bank of the Cumberland River. Pillow was to open an escape route by rolling up the Union right while Buckner sortied and struck the center. When the Union right flank had been pushed back, Pillow would lead the retreat to Charlotte and Buckner would serve as the rear guard.

The Confederate attack at 6:00 on the morning of the 15th caught Union troops completely by surprise. In a hard-fought close action the Confederates drove the Union troops back, although in good order. Buckner then sent men forward. Union troops soon used up their ammunition and were forced to retreat.

With the road to Charlotte open, Pillow now threw away the chance to escape. Imaging that he was in position to defeat Grant, he continued the attack. with the situation desperate, Union brigadier general Lew Wallace ordered his men forward, driving the Confederates back.

Grant now arrived on the scene and ordered the lost ground retaken. He also assumed that to break through, the Confederates must have weakened their lines elsewhere, and he ordered Brigadier General Charles F. Smith to mount an immediate attack on the Confederate right. Grant told an aide that the first side to attack with be victorious.

Smith then attacked, and his men soon breached Fort Donelson’s breastworks. Although Buckner finally halted the Union advance, he could not force the invaders out of the works, and the entire Confederate position was now in jeopardy. General Wallace’s division was also successful, retaking ground lost earlier.

Additional Federal infantry regiments reached the Fort Donelson area by river transport that evening, bringing Union strength to 27,000 men. It was now no longer possible for the bulk of the Confederates to escape. During the night of 16-17 February, Generals Floyd, Pillow and Buckner again met. With the situation hopeless, Pillow and Floyd decided to escape across the Cumberland. Buckner announced he would share the fate of the garrison and assumed command. Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest also got away with some 500 men on horseback; they forded the creek between the Union right flank and the river. In all, perhaps 5,000 Confederates escaped.

Early on the 16th, Buckner asked for an armistice and surrender terms. On General Smith’s urging Grant replied, “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Buckner then capitulated.

Some 15,000 Confederates surrendered at Fort Donelson. Union troops also secured a considerable number of small arms, 57 light and heavy guns, and equipment and rations. Estimates of Confederates killed and wounded vary from 1,500 to 3,500. Union losses were 2,832: 500 killed, 2,108 wounded, and 221 captured or missing.

The fall of Fort Donelson led directly to the Union capture of Nashville, the first Confederate state capital taken. The loss of Fort Donelson’s garrison also affected, perhaps decisively, the subsequent battle of Shiloh. - Spencer C. Tucker

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 728-731]

For further reading:

Knight, James R. The Battle of Fort Donelson: No terms but Unconditional Surrender.

Cooling, B. Franklin. Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland.

Tucker, Spencer. Unconditional Surrender: The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson.

Hurst, Jack. Men of Fire: Grant, Forrest and the Campaign That Decided the Civil War.

Pingback: Ulysses Simpson Grant - 18th U.S. President and General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army (1822-1885) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Bombardment of Fort Henry (Feb. 2-6, 1862) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, C.S.A. (Jan. 18,1816- May 16,1863) | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: On this date in Civil War history: April 6-7, 1862-Battle of Shiloh | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: Our Trip to Ft. Donelson and Wasp Duncan’s Trip to Hell | TheVillageSmith