The battle of Pea Ridge, also known by Southerners as the battle of Elkhorn Tavern, was the most famous engagement fought in the trans-Mississippi region. It also was the key to Union domination of that area, for Federal forces cleared Missouri of Confederate troops, turned back the most powerful Confederate army ever raise in the trans-Mississippi when it tried to invade the state, and opened the way for Union invasion attempts into the heart of Arkansas. The federal victory at Pea Ridge also supported the much more significant Union drive down the Mississippi River valley that split the Confederacy in two with Grant’s capture of Vicksburg.

Missouri was a battlefield from the very beginning of the war. Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon’s defeat and death at the battle of Wilson’s Creek on 10 August 1861 allowed Confederate major general Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard to occupy southwestern Missouri and threaten Union control of the Missouri River valley and the all-important city of St. Louis. Major General Henry W. Halleck, commander of Union forces in the state, organized a field force named the Army of the Southwest at Rolla to deal with Price. Brigadier General Samuel Ryan Curtis was appointed its commander and given the task of driving Price out of the state.

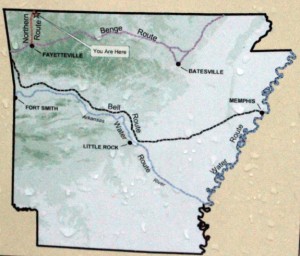

Curtis started his campaign on 11 February 1862 with more than 12,000 men. his army was divided into four small divisions, two of which consisted mostly of regiments dominated by European immigrants and under his second in command, Brigadier General Franz Sigel. Price’s 8,000 poorly trained and supplied Guardsmen could not hold Springfield alone, so Price evacuated the city and retreated along the Telegraph road into northwestern Arkansas. There he hoped to join forces with Brigadier General Benjamin McCullough’s 8,000 Confederate troops who had already cooperated with Price to win the bloody battle of Wilson’s Creek.

Curtis hotly pursued Price into Arkansas, hounding his fast-marching column day and night. Several skirmishes occurred along the Telegraph Road, including two fought on Arkansas soil near a hostelry called Elkhorn Tavern. Price joined with McCulloch just south of the tavern and the two retired all the way to the rugged Boston Mountains, forty miles away. Curtis ended his pursuit two miles south of Elkhorn Tavern and established a fortified defensive position on the northern bluff of Little Sugar Creek, astride the Telegraph Road. He had accomplished his primary task of clearing Missouri of Price’s Rebels and preventing them from interfering with Halleck’s push down the Mississippi valley, but Curtis had to stop and await developments because his extended supply line from Rolla was stretched to the breaking point.

Curtis hotly pursued Price into Arkansas, hounding his fast-marching column day and night. Several skirmishes occurred along the Telegraph Road, including two fought on Arkansas soil near a hostelry called Elkhorn Tavern. Price joined with McCulloch just south of the tavern and the two retired all the way to the rugged Boston Mountains, forty miles away. Curtis ended his pursuit two miles south of Elkhorn Tavern and established a fortified defensive position on the northern bluff of Little Sugar Creek, astride the Telegraph Road. He had accomplished his primary task of clearing Missouri of Price’s Rebels and preventing them from interfering with Halleck’s push down the Mississippi valley, but Curtis had to stop and await developments because his extended supply line from Rolla was stretched to the breaking point.

Price and McCulloch then received a new commander, Major General Earl Van Dorn, who was appointed to lead Confederate forces in the trans-Mississippi. An aggressive, ambitious general, Van Dorn reached Price and McCullogh on 2 March and immediately ordered an advance. With inadequate logistical and administrative preparation, the newly named Army of the West set out to gobble up Curtis’s army. The Federals received word of the advance in time to concentrate most of their army at Little Sugar Creek, except that Sigel’s rear guard of 600 infantry, artillery, and cavalry was nearly caught by Van Dorn’s mounted advance as it retreated from Bentonville on 6 March. Sigel, who personally led the rear guard, was able to cut his way through.

Rather than attack Curtis’s fortified position head on, Van Dorn marched around his right flank on a road known as the Bentonville Detour. This took him more than two miles to the rear of Curtis’s army and allowed him to place Price’s command on the Telegraph Road to cut off the Federal retreat. But the exhaustion of his troops forced Van Dorn to detach McCulloch’s command and send it advancing toward the Federal rear two miles to the west, with the imposing bulk of Pea Ridge between the two Confederate wings. Thus the battle of Pea Ridge, as it was fought on 7 March, took place on two widely separated fields with neither wing of Van Dorn’s command being able to support the other.

Curtis masterfully handled his army to take advantage of this mistake. he sent sufficient forces to oppose McCulloch near the village of Leetown, while placing a small delaying force in Price’s path at Elkhorn Tavern. The fighting at Leetown was a swirling, seesaw affair in which McCullough and his second in command were killed before they could fully deploy their forces. The third in command was then captured. The resulting breakdown of the chain of command immobilized a large part of this powerful division and greatly contributed to the smashing Union victory at Leetown. The action here was marked by the involvement of two regiments of Cherokee troops serving in Van Dorn’s army. Members of these units scalped and mutilated about a dozen dead and wounded Federal soldiers on the battlefield.

Curtis masterfully handled his army to take advantage of this mistake. he sent sufficient forces to oppose McCulloch near the village of Leetown, while placing a small delaying force in Price’s path at Elkhorn Tavern. The fighting at Leetown was a swirling, seesaw affair in which McCullough and his second in command were killed before they could fully deploy their forces. The third in command was then captured. The resulting breakdown of the chain of command immobilized a large part of this powerful division and greatly contributed to the smashing Union victory at Leetown. The action here was marked by the involvement of two regiments of Cherokee troops serving in Van Dorn’s army. Members of these units scalped and mutilated about a dozen dead and wounded Federal soldiers on the battlefield.

The fighting at Elkhorn Tavern was far more costly, sustained, and bitter than that at Leetown. The outnumbered Federals here, commanded by Colonel Eugene A. Carr, barely held their own under great pressure, and eventually they were forced to retreat after exacting a heavy price in blood from the Confederates. Nightfall and the exhaustion of Price’s men enabled Curtis to stabilize his position a few hundred yards south of the tavern.

That night, Curtis managed to concentrate his army to support Carr bringing his entire force together for the first time in the battle. Van Dorn’s ability to control his shattered army broke down. His ammunition train had strayed away from the battlefield the previous day and there was no reserve ordnance available, and much of McCullough’s division had already retreated southward. Faced with a powerful artillery barrage directed by Sigel and a nearly general advance of Curtis’s infantry, Van Dorn ordered his men to retreat before noon on 8 March. he managed to escape the battlefield and marched eastward and southward, thus making a complete circuit around Curtis’s army until he reached Van Buren, Arkansas.

The three days of fighting at Pea Ridge led to the loss of 1,384 of the 10,250 Federals who actually were engaged. Van Dorn lost about 2,000 of the roughly 14,000 Confederates engaged. It was a decisive Union victory. Van Dorn soon transferred his army east of the Mississippi to reinforce the Army of the Mississippi at Corinth. Curtis later marched his army across northern and central Arkansas and nearly captured Little Rock before occupying Helena on the Mississippi River, which was the southern-most town on the river held by the Union for many months to come. The long struggle to dominate the upper Trans-Mississippi was over. ~ Earl J. Hess

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1466-1468]

Click here to see the video of the Confederate Sunset at Pea Ridge taken in August 2011.

For further reading:

Shea, William L. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. University of North Carolina Press. 1997.

Knight, James R. The Battle of Pea Ridge: The Civil War Fight for the Ozarks. The History Press. 2012.