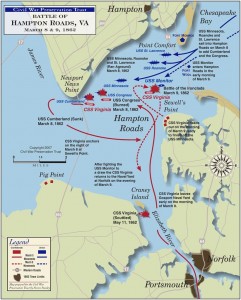

Confederate captain Franklin Buchanan steamed his ironclad Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack) from the Gosport Navy Yard into the Chesapeake Bay to confront the Union fleet there on blockade duty. Anchored in the bay were three coal ships and a hospital vessel; five tugboats and a side-wheel steamer; twelve gunboats mounting one to five guns; the screw frigates Roanoke and Minnesota; the storeship Brandywine; and the sailing frigates St. Lawrence, Congress, and Cumberland. The Union detachment had 188 guns and more than 2,000 seamen.

At 1:08 p.m., a lookout aboard the Roanoke spotted the approach of the slow-moving Confederate ironclad and raised the signal for the Union fleet. Within minutes, the Cumberland, the Congress, and the shore batteries at Newport News opened fire. Because the Union squadron was dispersed, Buchanan decided to close on the becalmed Cumberland first and then move against the other Union ships. At about 2:30 the Virginia fired its first devastating broadside into the Cumberland. After firing several more rounds, Buchanan rammed the wooden frigate and for thirty minutes maintained a murderous fire; shortly after 3:30 p.m. the Cumberland sank.

Next, Buchanan turned his ironclad against the frigate Congress, which had been towed into shoal waters to prevent the Virginia from ramming it. Within minutes the Confederate ironclad was about 200 yards from the grounded frigate and firing continuously into it. At 4:45 p.m., after enduring almost an hour of bombardment, the Congress struck its colors and raised a white flag. Even so, Union sharpshooters on shore continued firing on Confederates as they prepared to take the ship one shot wounded Buchanan in the leg and he had to be carried below to his quarters. Almost instantly Confederate shot struck the helpless frigate. By 5:00 p.m., the Congress was fully ablaze and out of commission. With dark approaching, Lieutenant Cateby ap Roger Jones, the executive officer who had assumed command because of Buchanan’s injury, anchored the ironclad under Confederate guns at nearby Sewell’s Point.

Next, Buchanan turned his ironclad against the frigate Congress, which had been towed into shoal waters to prevent the Virginia from ramming it. Within minutes the Confederate ironclad was about 200 yards from the grounded frigate and firing continuously into it. At 4:45 p.m., after enduring almost an hour of bombardment, the Congress struck its colors and raised a white flag. Even so, Union sharpshooters on shore continued firing on Confederates as they prepared to take the ship one shot wounded Buchanan in the leg and he had to be carried below to his quarters. Almost instantly Confederate shot struck the helpless frigate. By 5:00 p.m., the Congress was fully ablaze and out of commission. With dark approaching, Lieutenant Cateby ap Roger Jones, the executive officer who had assumed command because of Buchanan’s injury, anchored the ironclad under Confederate guns at nearby Sewell’s Point.

In only five hours, the Virginia sank two Union frigates (USS Cumberland and Congress), drove three steam frigates aground in shoal waters (Minnesota, St. Louis, and Roanoke), and exchanged fire with several small armed steamers and shore batteries while suffering virtually no damage. The Confederate ironclad had been responsible for killing almost 300 Federal sailors and wounding 100 more. The day’s battle proved conclusively that wooden warships had become obsolete.

Shortly after sunrise on 9 March 1862, Jones noticed that the Minnesota was still stranded and that it was not alone. During the previous evening, the strange-looking experimental ironclad Monitor, commanded by Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, had arrived from New York to protect the Union fleet. Even so, Jones intended first to finish off the Minnesota and then turn to the remainder of the Federal fleet in the Bay.

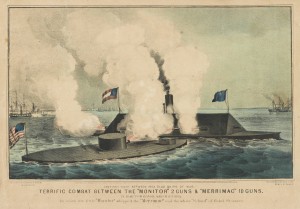

As the Virginia made its way the two miles from Sewell’s Point toward the Union fleet, Worden moved the Monitor into a defensive position between the grounded Minnesota and the approaching Confederate ironclad; the wooden frigate began firing broadsides that bounced harmlessly off the Virginia. Jones continued steaming toward the Minnesota until the pilots informed him that the ironclad could not close on the frigate because of shallow water. With that information Jones instead chose to fight the Monitor.

It was now about 8:45 a.m. as the two ships closed to within 50 yards, circling one another while trying to gain an advantageous position. The Virginia’s deep draft, poor steering, and slow speed left it at a disadvantage. The Monitor, with its shallow draft and efficient engines, was able to steam circles around the Confederate vessel. The ships moved as close as a few feet from one another and as far apart as 100 yards, all the while maintaining a constant fire. The eleven-inch solid shot from the Monitor’s guns dented the rebel vessel’s iron casemate and splintered its oak backing.

At about 10:30 a.m., after about two hours of almost continuous combat, disaster struck the Virginia. With all the circling and maneuvering, the pilots aboard the Confederate ironclad became disoriented and allowed it to run aground. With its 22-foot draft, the Virginia became mired in the muddy bottom of the Chesapeake Bay and was helpless against the Monitor. For the next fifteen minutes, the Monitor maintained against the Virginia a ceaseless fire, which cracked the iron sheathing and bent the timbers behind.

As Jones tried to extricate the Virginia, he realized that the Confederate cannon could not penetrate the Monitor’s turret or iron sheathing nor could his armor continue to withstand the pounding of the enemy’s guns. Jones concluded that his only recourse was to ram the Union ship. Aboard the Monitor, Worden realized Jones’s intentions, tried to avoid a direct collision, and instructed his men to continue firing on the Confederate vessel. The Confederate ship was too large, too unresponsive, and too slow to build up the speed necessary to inflict severe damage on the Union vessel. Moreover, shortly before the two ships made contact, Worden turned the helm hard, away from the Virginia. nothing had penetrated the Monitor’s half-inch iron hull, and no water flooded into the ironclad.

For fifteen minutes, as the Monitor withdrew from the fight to replenish its ammunition supply, Jones turned his attention again to the Minnesota. Worden decided, because his ship was faster and more maneuverable, that he should ram the Virginia’s stern; such a collision would damage the Confederate ironclad’s rudder and propeller, leaving it at the whim of the currents or at the mercy of the Union navy. Worden was able to maneuver his vessel to Jones’s stern and closed at full speed for the Virginia’s hull. But at the last moment, the Monitor’s steering failed and the ironclad missed its target by only a few feet.

Jones’s guns concentrated on the Monitor’s pilothouse as the Union ironclad approached, and at about 11:30 a.m., a shot struck one of the sight holes on the pilothouse and sent particles of paint and iron into Worden’s face. For the next twenty minutes, while Union officers attended Worden, the Monitor moved away from the Virginia. Although no one realized it at the time, the first battle between two ironclads had ended.

The two ships had sparred for almost four hours and had done minimal damage to each other. The engagement did provide a tactical victory for the Federals, as the Monitor had fulfilled its primary objective of saving the frigate Minnesota. The battle allowed the Confederates to maintain strategic control over Hampton Roads and the James River; Union forces could not move against Norfolk, and General George B. McClellan had to modify his spring 1862 campaign against Richmond. Although many realized that neither side could claim outright victory, they did acknowledge that history had been made as the two ships had helped to revolutionize naval warfare.

- Gene A. Smith

[Source: Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History. W.W. Norton & Co. 2002. pp. 1348-1349]

For further reading, see:

The Monitor, the Merrimack…and U.S.S. Minnesota?

Iron tomb of USS Monitor gives up faces of its dead

Forensic Reconstructions Reveal the Faces of Civil War Sailors (Popular Mechanics)

Battle of Hampton Roads weekend at the Mariner’s Museum

Civil War in Hampton Roads (DVD)

Holzer, Harold. The Battle of Hampton Roads: New Perspectives on the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia. Fordham University Press. 2006.

Hoehling, A.A. Thunder at Hampton Roads. DaCapo Press. 1993.

Konstam, Angus. Duel of the Ironclads: USS Monitor and CSS Virginia at Hampton Roads 1862. Osprey Publishing. 2003.

Nelson, James L. Reign of Iron: The story of the First Battling Ironclads, the Monitor and the Merrimack. Harper Perennial. 2005.

Pingback: The Monitor, the Merrimack and… U.S.S. Minnesota? | This Week in the Civil War

Pingback: The Monitor vs Merrimack - 150 years ago today - Message Boards