By Jeffrey S. Williams

Most days were filled with some sort of military activity during November 1863 and the second day of the month was no exception. Skirmishing occurred at Bayou Bourbeau, Louisiana; Bates Township, Arkansas; Corinth, Mississippi; along with two locations in Tennessee. Brigadier General John McNeil assumed command of the Federal District of the Frontier which contained the area in southern Kansas, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), southwestern Missouri and western Arkansas. Additionally, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks and his expeditionary force in the Rio Grande occupied Brazos Island in an attempt at gaining a foothold in Texas. There was a lot to occupy the mind of the chief executive in Washington.

Considering the military operations, President Abraham Lincoln nearly dismissed a letter that he received on Nov. 2, 1863 from Pennsylvania attorney David Wills, president of the Soldiers National Cemetery Association in Gettysburg. Having already extended the invitation to Edward Everett to give the keynote address, the ceremony date was already chosen for Nov. 19. Everett previously served as a member of Congress, U.S. Senator, governor of Massachusetts, Secretary of State, president of Harvard University and was the vice presidential candidate for the Constitutional Union Party in 1860 behind John Bell. Everett, who agreed with Lincoln on the need for the preservation of the Union, was one of the country’s most sought after orators in 1863.

In his letter to Lincoln, Wills wrote, “It is the desire that, after the Oration, you, as Chief Executive of the Nation, formally set apart these grounds to their Sacred use by a few appropriate remarks. It will be a source of great gratification to the many widows and orphans that have been made almost friendless by the Great Battle here, to have you here personally; and it will kindle anew in the breasts of the Comrades of these brave dead, who are now in the tented field or nobly meeting the foe in the front, a confidence that they who sleep in death on the Battle Field are not forgotten by those highest in Authority; and they will feel that, should their fate be the same, their remains will not be uncared for.”

Because Wills’s papers have disappeared, Lincoln’s reply is unknown, though it is known that the president sent two letters to Wills after receiving the invitation and prior to arriving in Gettysburg.

After the July 1-3, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, which pitted over 93,000 Federal troops of the Army of the Potomac against nearly 75,000 Confederates in the Army of Northern Virginia, nearly 50,000 troops from both sides were casualties of war either killed, wounded or missing. The Evergreen Cemetery Association, led by attorney David McConaughy, planned on creating a soldiers annex to the town cemetery, requiring fee payments for internments. McConaughy had already purchased land on cemetery hill for the annex, had ordered the burial of 100 soldiers inside Evergreen Cemetery, and had secured agreement from nearby landowners for the purchase of their property.

After the July 1-3, 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, which pitted over 93,000 Federal troops of the Army of the Potomac against nearly 75,000 Confederates in the Army of Northern Virginia, nearly 50,000 troops from both sides were casualties of war either killed, wounded or missing. The Evergreen Cemetery Association, led by attorney David McConaughy, planned on creating a soldiers annex to the town cemetery, requiring fee payments for internments. McConaughy had already purchased land on cemetery hill for the annex, had ordered the burial of 100 soldiers inside Evergreen Cemetery, and had secured agreement from nearby landowners for the purchase of their property.

Wills superseded that effort with the Soldiers National Cemetery Association plan and sought Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin’s assistance in the project while accusing McConaughy of land speculation and profiteering.

It was a July 17, 1862 law passed by Congress which allowed the president “to purchase cemetery grounds and cause them to be securely enclosed, to be used as a national cemetery for the soldiers who shall die in the service of the country” and both McConaughy and Wills were aware of the ramifications of this law on the Borough of Gettysburg in light of so many thousands of Federal soldiers who were killed during the three-day battle. Fourteen national cemeteries had already been established in the initial six months after passage of the act.

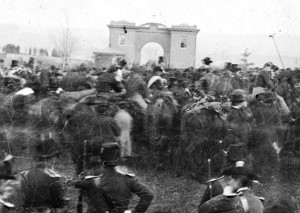

This Nov. 19, 1863 photo made available by the Library of Congress shows the crowd assembled for President Abraham Lincoln’s address at the dedication of a portion of the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pa. as a national cemetery. “The battlefield, on that sombre autumn day, was enveloped in gloom,” Joseph Ignatius Gilbert, a freelancer for The Associated Press at the time, wrote in a paper delivered at the 1917 convention of the National Shorthand Reporters’ Association in Cleveland. “Nature seemed to veil her face in sorrow for the awful tragedy enacted there.” (AP Photo/Library of Congress, Alexander Gardner)

McConaughy and Wills reached an agreement on the cemetery location in early August that the State of Pennsylvania would purchase 17 acres of land from the Evergreen Cemetery Association for the sum of $175 for the purposes of establishing the national cemetery there. This occurred at roughly the same time that Major General Darius Couch, who on Aug. 10, decreed that there would be no battlefield disinterments allowed during the months of August and September in order to halt the removal of bodies from the battlefield by families during the hot summer months. However, design work on the national cemetery was allowed to proceed.

William Saunders, landscape gardener for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, designed the cemetery in a semi-circle surrounding a central monument. Frank W. Biesecker won the contract to rebury the remains at the cemetery for the sum of $1.56 per person. His bid was the lowest, though 33 others ranged from his amount up to $8 per person. Biesecker hired Samuel Weaver, a teamster, as superintendent of the exhumation process. Basil Biggs and a team of approximately 10 people working underneath Weaver transported the empty coffins from the train station to the burial sites, helped disinter the bodies and transported them to the new cemetery for reburial. Surveyor and Superintendent of Burials James S. Townsend worked with Saunders to lay out the plots and mark each grave while John B. Hoke was responsible for digging the graves and burying the coffins. Weaver and Townsend compared their notes each day and then presented them to Wills for entry into the permanent record.

The first bodies, Corporal William Wallace Story, 3rd Indiana Cavalry Company E., and Private Ebenezer H. James, 121st Pennsylvania Infantry Company A, were exhumed from the Presbyterian graveyard on North Washington Street on Oct. 27, 1863 and soon soldiers were being reburied at the rate somewhere around 100 per day. The process continued until March 18, 1864 when the final grave was dug.

A special train of four cars provided by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad left Washington on Wednesday Nov. 18, 1863, headed north to Baltimore and then was transferred to the North Central Railroad to Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania where it was switched again to the Hanover Railroad for the final leg, arriving at Gettysburg at 5 p.m. Though his son, Tad, was ill, which greatly distressed the president, and his wife, Mary Todd was greatly upset, President Lincoln regained his composure enough to tell a few yarns to his travel companions.

While Lincoln and his entourage ate dinner at the 12-room Wills house, masses of people gathered in the square outside to get a glimpse of the president. Pressured from the crowd, Lincoln emerged briefly and remarked, “I appear before you, fellow citizens, merely to thank you for this compliment. The inference is a very fair one that you would hear me for a little while at least, were I to commence to make a speech. I do not appear before you for the purpose of doing so, and for several substantial reasons. The most substantial of these is that I have no speech to make.” The crowd laughed. “In my position it is somewhat important that I should not say any foolish things,” Lincoln continued.

While Lincoln and his entourage ate dinner at the 12-room Wills house, masses of people gathered in the square outside to get a glimpse of the president. Pressured from the crowd, Lincoln emerged briefly and remarked, “I appear before you, fellow citizens, merely to thank you for this compliment. The inference is a very fair one that you would hear me for a little while at least, were I to commence to make a speech. I do not appear before you for the purpose of doing so, and for several substantial reasons. The most substantial of these is that I have no speech to make.” The crowd laughed. “In my position it is somewhat important that I should not say any foolish things,” Lincoln continued.

Someone interrupted the president with the quip, “If you can help it.”

“It very often happens that the only way to help it is to say nothing at all,” Lincoln retorted which received more laughter. “Believing that it is my present condition this evening, I must beg of you to excuse me from addressing you further.”

The pacified crowed then sought out other dignitaries for speeches while the president continued working on the draft of his speech until 11 p.m., when he summoned his guard, Sergeant H. Paxton Bigham, 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry Company B, to escort him to the home of Gettysburg Sentinel editor Robert G. Harper, his speech was tucked into the president’s pocket.

Upon their return, a crowd had gathered once again. Lincoln said to Bigham, “I wish to return to my room. You clear the way and I will hold on to your coattails.” They made their way indoors without incident.

Early on the morning of Nov. 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward took a carriage ride through a portion of the Gettysburg battlefield, returned to the Wills House for breakfast and by 9 a.m. was found in his room going over the final draft of his speech.

Early on the morning of Nov. 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward took a carriage ride through a portion of the Gettysburg battlefield, returned to the Wills House for breakfast and by 9 a.m. was found in his room going over the final draft of his speech.

Around 10 a.m., Lincoln, dressed in black and wearing white gauntlet gloves, departed the Wills House for the procession to the cemetery on the back of a gray mare. The procession went down Baltimore Street, turned right on Steinwehr Avenue, turned left a block later onto the Taneytown Road and into the cemetery. Approximately 15,000 people attended the dedication ceremony and lined the streets to watch the procession. It was reported that Lincoln bowed with a modest smile and uncovered his head to the throng of men, women and children that greeted him from the doors and windows.

Scars from the battle were more apparent the closer they got to the cemetery as rifle pits, cut and scarred trees, broken fences, pieces of artillery wagons and harnesses, scraps of blue and gray clothing and bent canteens still littered the area.

Once the full delegation entered the cemetery, the ceremony began with “Homage d’uns Heros” played by Adolph Birgfield’s Band of Philadelphia, and then Reverend Thomas H. Stockton, chaplain of the U.S. House of Representatives gave the invocation.

After the U.S. Marine Corps Band played “Old Hundred,” Edward Everett, the keynote speaker, began his remarks. “Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature,” Everett said.

After the U.S. Marine Corps Band played “Old Hundred,” Edward Everett, the keynote speaker, began his remarks. “Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature,” Everett said.

The keynote address was 13,607 words and took one hour and 57 minutes to deliver. Wilson G. Horner’s Musical Association of Baltimore sang a “Consecration Hymn” as a musical interlude before U.S. Marshal Ward Hill Lamon introduced the president.

Lincoln then stepped to the front of the platform around 2 p.m., adjusted his glasses and set down the manuscript of the speech he had prepared in Washington, instead taking the same paper from his coat pocket that he had during his visit with the Gettysburg Sentinel editor and began his “few appropriate remarks.”

19th November 1863: Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States of America, making his famous ‘Gettysburg Address’ speech at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery during the American Civil War. Original Artwork: Painting by Fletcher C Ransom (Photo by Library Of Congress/Getty Images)

The speech that he delivered, known to history as the Gettysburg Address, is only 272 words in length and took just a few minutes to deliver. After a long applause for the president, Birgfield’s Band of Philadelphia played a hymn and a volunteer choir from the churches in Gettysburg sang. Then Reverend Henry Louis Baugher, president of Gettysburg College, delivered the benediction, and the ceremony concluded. The artillery fired a salute and the military delegation reformed to escort Lincoln back to the Wills House, where Lincoln received visitors for an hour.

The president had specifically requested to meet with John Burns, a 70-year old civilian who fought at the battle on July 1, 1863. After meeting the president at the Wills House, the two walked down Baltimore Street together to the Presbyterian Church of Gettysburg at the corner of Baltimore and East High Streets for the final ceremony of the day. Lincoln and Burns sat beside each other during the ceremony. However, Burns fell asleep during a speech by Ohio Lieutenant Governor Charles Anderson. Lincoln, however, needed to return to the depot to catch the train back to Washington and left Burns undisturbed.

As the president mentioned the previous day that he was not feeling quite well, Lincoln was feverish, weak and had a headache when he boarded the train at 6:30 p.m. A vesicular rash and lengthy illness and diagnosis of a mild case of smallpox followed upon his arrival at the White House.